Source:A orillas del Potomac

It was only logical that from the end of the 19th century until the 1980s, in California and in the country as a whole, Fray Junípero Serra was considered the “founding father of California”. Since 1931, the statue of the Franciscan friar has stood in the National Statuary Hall of the Capitol in Washington, D.C., by decision of the California Congress. The Indians were still (in the mid-18th century) in the Paleolithic period – the final transitional period of which was the Stone Age – as simple hunter-gatherers, almost completely unaware of agricultural practices, activities that define the beginning of the Neolithic.

Spanish colonisation introduced advanced European thinking and techniques to the territory. Modernity came to California – first and foremost – from the Spanish, not from the Anglo-Saxons on the East Coast, and certainly not from the Indians themselves. California’s subsequent incorporation into the great American nation (1850) was facilitated by the economic, social and cultural foundations laid by the Spanish colonisers.

A chronology of the colonisation of California from 1542 to 1850 appears at the end of this article.

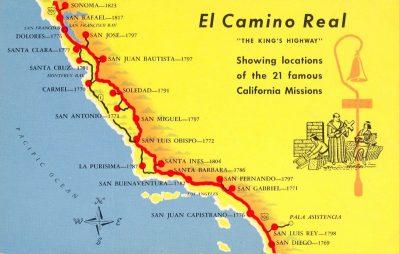

The colonisation of California was based on four fundamental elements: the 21 (Franciscan) missions, the four presidios (military forts), the pueblos (which were few in number and were inhabited by Spanish settlers and mestizos from present-day Mexico) and the roads. All this was distributed along a long coastal strip of almost 1,000 km.

After its establishment along the coast, progress was spreading and the territory was structured in a functional way, which was already done by the settlers from the eastern United States. Settlers began to arrive from 1830, very gradually, until the gold rush that took place right in the middle of that century: 1848 to 1855.

In 1821, the Spanish presence in those lands came to an end (after almost 280 years), when Mexico won its independence from Spain and, with it, obtained the administration of all that had belonged to the Crown of Spain, which covered a large part of the current territory of California, although the missions were established only in the coastal area, being there where the Spanish influence was greater and more lasting.

(In August 2019 I have published a new article on the fate of California’s indigenous peoples under Spanish rule and, later, under US power, when they were almost exterminated.)

Kick-starting the colonisation drive

The Spanish Crown had laid claim to the territory of California ever since one of its illustrious navigators – a Portuguese national – Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, discovered and sailed the entire coastline in 1542. He was the first European to do so. But for the next two centuries, colonisation could hardly be undertaken. The penultimate section of this article provides the explanation for this delay.

Until 1765 this territory remained totally virgin and primitive, but the Viceroy of New Spain (now Mexico) felt the need to make that “claim” effective in the face of rumours of attempted westward expansion of the British Empire and French Louisiana, and the increasing incursions of Russian fur-trading ships from the eastern tip of Siberia down the American coast from Alaska.

In 1767 the Society of Jesus was expelled from Spain and its dominions. In the previous seven decades (from the late 17th century, 1697), the Jesuits had established eighteen missions along the long, narrow peninsula of California (now in Mexico), then known as Baja California.

Although it is beyond the scope of this article, let it be said that – prior to the Californias – numerous Catholic missions had been founded in what are now the states of New Mexico (some 35) and Arizona (14). The first of these, Nª Sª del Perpetuo Socorro, was established by the Franciscans in the early date of 1598 in what is now the city of Socorro, located more or less in the centre of the state of New Mexico. The great majority of these missions were the work of the Franciscans, but in southern Arizona, they were the work of the Jesuits.

Returning to the course of the story, let us say that after the expulsion of the Jesuit order from Spain in 1767, the authorities of the Viceroyalty decided that the Franciscan order should take over the running of these missions from the Jesuits and, in addition, extend the mission system much further north, to almost the entire coast of what is now California, some 1,000 km long, as far as San Francisco. Fray Junípero Serra was in charge – in 1769 – of this enormous task, accompanied by a (very) few military men.

Early life and work of Fray Junípero Serra

Fray Junípero Serra was born on the island of Mallorca in 1713. He was ordained Franciscan at the age of 16. He soon became an eloquent preacher, reaching the position of professor of theology. His dream was to go to America as a missionary. In 1749, at the age of 36, he landed on the Caribbean coast (city of Veracruz) of the territory of New Spain (present-day Mexico), beginning his new life.

From 1749 to 1768 Fray Junípero Serra stayed intermittently in Mexico City at the Apostolic College of San Fernando, which, besides serving as a secular centre of education, acted as the Order’s headquarters for part of New Spain. Serra often travelled in his missionary work to different areas, but always to places where many of the indigenous people had already been baptised.

In March 1769, at the advanced age of 56, Junípero Serra set out by land from the city of Loreto (Baja California peninsula) to San Diego Bay (today in the USA): 1,100 km, basically following the Pacific coast. Shortly after his departure, he began to meet Indians who had not been evangelised, which caused him great excitement. Three months later, on 1 July 1769, he reached San Diego Bay.

The overland expedition incorporated cattle, swine, and equines (horses and burros), which the northern Indians had hardly ever seen before. (The Spanish Frontier in North America. Brief Edition.David J. Weber. 2009. Yale University. Pp. 23-24) Nor did they know the wheel, or writing, or metals: almost all the arrowheads and spearheads of the time used stones, such as silex, which defined the Stone Age.

A couple of ships had sailed into the bay, carrying various supplies and victuals.

The colonisation of California, then known as Alta California, began.

Colonisation work on the coast of Alta California

Within two weeks of his arrival, on 16 July 1769, Fray Junípero Serra officially founded his first mission, in San Diego.

From this humble act grew the pueblo and, much later, the city of San Diego (USA). Today, with 1.4 million inhabitants, it is the second largest city in the state.

At that time, in 1769, an basic military fort (presidio) was also set up in San Diego with 8 soldiers and 14 Catalan volunteers. Over time, adobe walls were built; later, they were replaced by stone walls. In general, the builders were the soldiers themselves, directed by a craftsman sent from New Spain. The friars were accompanied by eighteen Indians from Baja California, who did not get along with the locals either. (Junípero Serra. Rose Marie Beebe and Robert Senkewicz. Univ. Oklahoma Press. 2015. P. 209)

Those 40 people (military and civilian) constituted the first contingent of the Spanish “invasion force” that, according to today’s American do-gooders, subjugated tens of thousands of coastal Indians. They should have been supermen, to accomplish such a feat.

Three friars – Fray Junipero Serra and two others – were responsible for starting the fledgling mission of San Diego, which existed only on paper. The colonisation of California had begun.

The second mission was founded very quickly the following year (1770) much further north, along Monterey Bay, more than 700 km from San Diego. The immediate reason for this great leap northward was the governor of Las Californias (Baja and Alta) feared that the Russian empire – which had already done some naval exploration – would overtake Spain in claiming those coasts.

The navigator Sebastián Vizcaino had been the discoverer (for the Europeans) of the bay and its qualities as a natural harbour in 1602, and had named it Monterrey (in honour of the Viceroy of New Spain). He then built a rudimentary wharf in the bay.

The new mission in the bay was called San Carlos Borromeo del Carmelo, but it is simpler to call it Carmel mission.

At the same time as the mission, Governor Gaspar de Portola directed the construction of a presidio (that is, a fort), also in 1770. The second to be built.

Monterrey was conceived as the main Spanish bastion on the entire Alta California coast.

Eventually the mission, port and fort gave rise to a pueblo and, later, to the present-day city of Monterey.

Monterey was the first capital of California, for 70 years: from 1777 (under Spanish rule) until 1849, when the US had just taken it from independent Mexico (in 1847).

The military man from Lérida Gaspar de Portolá Rovira was the first governor of the Californias (Baja and Alta), between 1767 and 1770. The second was Fernando Rivera y Moncada (1770 to 1774). The third, Felipe de Neve: 1775 to 1782.

In 1776 Fray Junípero Serra founded the San Francisco de Asís mission, at the northern tip of the peninsula of the same name, on the southern shore of the now Golden Gate Strait. Because it was located along the stream of Our Lady of Sorrows, it was also known as Mission Dolores (sorrows). Another military fort (presidio) was erected nearby, marking the northern end of the Spanish military presence.

On 4 July of that year, 1776, settlers on the east coast of the continent proclaimed the US Declaration of Independence from Britain. Until more than 60 years later (1835), those settlers knew nothing of what was happening on the Pacific coast.

The mission and the fort were the origins of the present-day city of San Francisco.

Until 1782, the Franciscan friar founded a total of 9 missions which, after his death, expanded to complete the system of 21 missions, which can be seen in the map above. More information on the Spanish missions in California can be found on the website of the Spain-USA Council Foundation.

The defensive system was completed with a fourth fort (presidio) on the coast of Santa Barbara (NW of present-day Los Angeles), along with the three already mentioned: San Diego, Monterey and San Francisco, from south to north. The total distance from one end to the other was almost 1,000 km.

From San Diego onwards, successive missions were built at a distance of about 48 km, i.e., a day’s ride on horseback.

The stability of these missions was striking in comparison to what happened in other regions of North America.

In general, the missions were founded very close to the coast, except in cliff areas and coastal mountain ranges, where they had to be built some 30 km inland. In other words, much of today’s California State Highway 1 (which runs through the Big South and beyond) runs close to the road the Spaniards laid out.

In any case, this road was never given the proper character of width and maintenance of the Caminos Reales (Royal Roads) proper, such as the Inland Road which, from Mexico City went all the way to the north of the present state of New Mexico, near the Colorado border: 2,500 km in length. The scarce traffic on the Californian coastal road and the very small number of settlers did not require such an effort.

The interesting blog La América española contains, among many others, an article with an extensive and illustrative presentation of the Spanish missions in the USA, including those in California.

The evangelising work of the missions

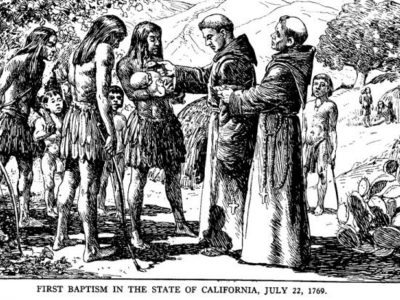

The conversion of the Indians to Catholicism was the primary concern of the Franciscan friars who created and directed the missions; this was the raison d’être of this network of missions, although the civil authorities also pursued colonisation and the reclamation of these lands in the face of foreign powers.

The baptism of the local Indians was a decisive act, as a careful record was kept of the baptisms performed in each mission. These records, written down, have allowed a good knowledge of the baptisms performed.

From 1776 to 1835, Franciscan friars baptised a total of more than 80,000 Alta California Indians. (Junipero Serra. Steven W. Hackel. Hill & Wang. 2013. Hardcopy. p. 239).

Of course, being almost 60 years old, this included more than one generation of these populations. On the other hand, many of the baptised children died early from disease.

In any case, it is worth noting that Sherburne F. Cook, the American who most carefully studied the demographic evolution of these Indians, estimated the number of Indians living in 1769 in the coastal area between San Diego and San Francisco at more than 60,000. (The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970. S. F. Cook. Univ. of California Press. June 1976. P. 42. Northern, central and southern mission areas included).

The conclusion is inescapable: a majority of the entire indigenous population of coastal Alta California agreed to be baptised, for more than half a century, on a basically voluntary basis, although there was surely some degree of pressure, which is the least that has happened in any religious expansion (such as Muslim) into foreign lands.

Could a handful of friars and about two hundred Spanish soldiers have forced tens of thousands of Indians to be baptised against their will, as today’s indigenist intellectuals claim?

Characteristics of the missions and presidios

The main purpose of Fray Junípero Serra and the Franciscan order was the evangelisation of the local Indians, on whose side they often took a stand against the first Spanish settlers and, from time to time, the military – whose duties could, of course, create friction with the locals.

The Mallorcan friar decided to undertake the construction of the churches with his own means, for which he almost always had the – voluntary – help of local Indians. This was usually done with lime and stone, which has left a unique architectural imprint in California.

The church was the symbol of the definitive establishment of Christianity in those lands and a place of religious congregation for the Indians and also for the Spaniards and the numerous mestizo civilians of Mexican origin.

There were almost always only 2 Franciscans dedicated to leading a mission (Junípero Serra. Rose Marie Beebe and Robert Senkewicz. Univ. Oklahoma Press. 2015. Hardcover. P. 354)

In 1776, for example, there were only 18 friars in all of Alta California (R. M. Beebe, p. 375), in the 7 missions that had been founded up to that point.

At first, the friars were accompanied by a handful of Indians from Baja California (now part of Mexico) – as helpers for all sorts of tasks – who were progressively replaced by Indians from the local tribes.

In the entire coastal territory (almost 1,000 km long), the number of Spanish military and soldiers was always very small: in 1777, for example, only 150 (“Felipe de Neve”. Edwin A. Beilharz. 1971. California Historical Society). At that date, there were already 3 forts and 8 missions.

Nearly twenty years later, in 1794 (during a period of tension with Britain), the total Spanish garrison, including officers, was only 218 in Alta California. (The Spanish Frontier in North America. David J. Weber. 2009. Yale University. Paperback. P. 191) At that date, the 4 forts and 13 of the missions were already in operation.

With the entire system in place – the 4 presidios and 21 missions – by 1820, in the absence of data known to me, the total number of soldiers and soldiers could tentatively be considered to have reached a maximum of 250.

Artist conception of the San Francisco Presidio in the 1790s.

In each presidio (fort) there were usually around 40 military personnel, although this varied considerably over time. Each presidio was responsible for the security of between 4 and 6 missions – about 250 km of coastline.

At each mission (where there was no fort nearby) there was a quasi-permanent guard of about 5 soldiers; see “Soldiers’ Duties”.

Soldiers and soldiers were allowed to live with their families. Often, at the end of their tour of duty, they remained in these places as civilians, cultivating the land or tending their livestock. This contributed to the settlement of California, with a civilian component.

A certain number of Spanish or mestizo civilians from New Spain (now Mexico) settled in the missions and presidios. In this way, pueblos were formed, usually around the mission church, and their agricultural activity spread, for which they needed labour, which they sought to obtain from the local tribes.

In the colonisation of California, the Indians were never enslaved.

The Indians were never treated as slaves, which was not only hypothetically impossible, if for no other reason, because of the small number of Spanish forces compared to the tens of thousands of Indians, but also because it was strictly forbidden by the Spanish Crown since the Ordenanzas (Laws) of Burgos in 1513.

According to the California Mission Studies Association (1997), the economic and social impact of the forts on California’s future was considerable and lasting, as “soldiers [and officers] and their descendants became part of California’s future rancho elite, along with the civilian families who settled and with whom they established marital relationships”.

According to Indigenist history professor Steven W. Hackel, just as Spain lost California and Mexico, there were some 3,200 Spanish and mestizo settlers from New Spain throughout Alta California in 1821. (Indian Authority in the Missions of Alta California. Steven W. Hackel. The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Series, Vol. LIV, No. 2, April 1997. P. 347) (Also, The Spanish Frontier in North America. David J. Weber. Yale University. 2009. Paperback. P. 194)

That figure equates to an average of about 140 colonists at each of the 21 missions. A rather small number as a colonising force, clearly outnumbered by the Indians.

In any case, the total number of settlers was concentrated mainly around the four forts (San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterrey and San Francisco) and the two pueblos of Los Angeles and San José.

Other important Spanish-founded cities in California

On September 4, 1781, the governor of Las Californias, Felipe de Neve Padilla, founded El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles del Rio de Porciúncula, the origin of the present-day city of Los Angeles, once Neve received the approval of Carlos III. Earlier, the navigator Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo had explored the coast of Los Angeles in 1542, claiming it for the Crown of Spain.

At the southern end of San Francisco Bay, the Spanish founded the pueblo of San Jose in 1777. Today it is the third-most populous city in California (1 million inhabitants) and is one of the main urban centres of Silicon Valley, home to the headquarters of Cisco Systems, PayPal, SunPower, eBay… and several public and private universities (such as Stanford).

(Voluntary) incorporation of Indians into the mission and pueblo system

By around 1821, “most of the missions in Alta California had between 500 and 1,000 resident Indians, two missionaries, and an armed garrison of 4 to 5 soldiers”. This is according to history professor Steven W. Hackel, a notorious exponent of Californian do-gooderism (Indian Authority in the Missions of Alta California. Steven W. Hackel. The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Series, Vol. LIV, No. 2, April 1997. P. 348)

As this same author states (in the same article) “in 1821 … the number of Indians inhabiting the missions (21,750) exceeded the total number of military and settlers (in the region): about 3,400“. (Indian Authority in the Missions of Alta California. Steven W. Hackel. The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Series, Vol. LIV, No. 2, April 1997. P. 247)

Not superior, but far superior (almost three times as much), so much so as to have made any attempt at defence impossible if the Indians as a whole had felt humiliated, oppressed or “enslaved” by the Spanish.

Moreover, this assumes that more than half of all the Indians in the coastal zone (which in 1821 must have been as many as 40,000, or perhaps less) chose to live alongside the missions – those 21,750.

If oppression and domination by force had been the only major factor in the colonisation of California, it could not have taken place.

Contradictions pile up (with numbers to boot) that do not sit well with American do-gooders, historians or not.

The high death toll from infectious diseases

This important and very serious issue has already been dealt with at some length in my article of 25 September 2018.

From that article I would simply like to repeat the following:

“Throughout the Americas, after the first encounters with Europeans, the local populations were literally decimated (90% of them perished), until several decades later, the survivors began to develop their immune systems to cope with the new health threats”.

“Neither the Spanish, nor the British, nor the French intentionally spread those diseases, so the term ‘genocide’ is totally inappropriate, a lie, in line with the Black Legend against Spain”.

Did the Spanish empire really not pay enough attention to California?

Although this is a rather tangential criticism of Spain’s enormous conquering and colonising work in the 16th, 17th and first half of the 18th centuries, it is worth providing a brief explanation of what, for example, the serious 20th-century American historian Paul Johnson, explains in his extensive work “A History of the American People”.

Paul Johnson was astonished that:

“Considering the benevolent climate, the fertility of the soil, and the existence of vast natural resources, it is surprising that the Spaniards … made so little effort to make use of what they found in California”. An elegant but thinly disguised criticism of conquering Spain, in which he is wrong.

For the sake of brevity:

- Simultaneously with the discovery of the California coast (1542), the Crown of Spain was embarked on the greatest and most rapid imperial expansion ever known. The Spanish coastline of South America alone, excluding Brazil, the Isthmus and Mexico, is 32,000 km long. In the Pacific Ocean, in addition to the Philippines, the Spanish discovered dozens of other archipelagos: the Mariana Islands, New Hebrides (today Vanuatu), Palau, the Carolinas, the Solomons, New Guinea, the island of Guam, etc.

- The prevailing winds off the Californian coast were very adverse, and strong storms occurred with some frequency. During the winter it was very difficult to sail.

- The coasts along which sailors sailed up from Mexico offered very few bays for shelter in bad weather, only three: San Diego, Monterrey and San Francisco, the only ones existing for 950 km. Further north, there are none for hundreds of kilometres.

- Much of that coastline is made up of cliffs, which made access to inland land, drinking water and food difficult. Those who have travelled there will not have forgotten the Big South.

- The “fertile lands” to which Paul Johnson refers are almost never near the coast, but in the so-called Central Valley (parallel to the coast), about 100 km from the ocean, with mountain ranges in between, sometimes.

- California was far from and poorly communicated with New Spain (present-day Mexico). The Mexican port of departure for these expeditions, San Blas (Nayarit), is about 3,000 km from San Francisco. The vast Sonoran Desert (260,000 km2, equivalent to half the size of the Iberian Peninsula) in NW Mexico made overland travel very difficult. Immediately to the north, the Mojave Desert (124,000 km2, 50% larger than Andalusia), east of Los Angeles, prevents almost all land transit, except for a narrow strip leading to that metropolis.

In short, even intelligent people without many anti-Spanish prejudices, such as Paul Johnson, sometimes “slip” in their judgements about the colonisation of California.

[In July 2021 I have introduced some additional information].

Brief chronology of the colonisation of California.

Cabrillo Boulevard, Santa Barbara, CA

1542. The Portuguese navigator Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, commissioned by the Crown of Spain, was the first European to sail along the west coast of the present-day USA. Specifically, he discovered San Diego Bay (just south of the present-day state of California), giving it that name. They had set sail from the coast of New Spain (present-day Mexico). He travelled and drew up marine charts -incomplete- of the entire Californian coast; they did not identify Monterey Bay, nor that of present-day San Francisco, the mouth of which is very narrow. He reached a good part of the coast of what is now the state of Oregon, north of California.

1579. The British pirate Francis Drake reached the Pacific coast of California that year, but the British Crown did not return to the coast until the 1820s. Drake’s claim to be the discoverer of that coast is clearly erroneous or misleading.

1602. Sebastian Vizcaino, Spanish explorer and diplomat (first ambassador to Japan), was the first European to discover Monterrey Bay, sailing from Mexico, founding a small port named Monterrey (in honour of the Viceroy of N. Spain). He also failed to notice San Francisco Bay. They went up the coast some 500 km north of San Francisco Bay to Cape Blanco, already within the boundary of the present state of Oregon. Thirty-six maps were drawn up, with some accuracy, of almost the entire Californian coastline, which would be used for navigation in the area until the 19th century. But neither military forts nor stable civilian settlements were created.

1769. The colonisation of California by the Spanish began on a permanent basis. Since in 1767, the Society of Jesus had been expelled from Spain and its territories in America (for its involvement in the Esquilache revolt), the Franciscan order was entrusted with the task of initiating evangelisation in what is known as Alta California, specifically the coast of present-day California. Fray Junípero Serra led this task from the very beginning. The Jesuits had previously established 18 missions in Baja California (a long peninsula, now in Mexico) and a variable number (because unstable) in the present state of New Mexico (notably Santa Fe) and a few in Arizona.

1769. It was a Spanish land soldier, Gaspar de Portolá, who discovered the great San Francisco Bay in that year.

1769 to 1782. Fray Junípero Serra founds the first 9 missions in present-day California. San Diego (San Diego de Alcalá) was the first in 1769, later giving rise to the city of the same name in the USA.

1775. In this year Juan Bautista de Anza led an expedition from the Túbac presidio (southern Arizona) to the San Gabriel Mission (east of Los Angeles), some 850 km long. It skirted the dangerous and vast Sonoma Desert, thus opening another route for the settlement of new California settlers from New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana and further afield.

1776. Fray Junípero Serra founds San Francisco de Asís Mission on the northern tip of a peninsula at the entrance to a bay, now called San Francisco Bay. From this mission, the city of San Francisco was created. That same year, on 4 July, in the city of Philadelphia, the US Declaration of Independence was made public. On the east coast, no one knew anything about what was happening on the other coast, more than 4,000 km away.

1783 to 1823. The Franciscans founded 12 more missions, bringing the total to 21 in California. The last one, in 1823 – when the area already belonged to Mexico – was San Francisco Solano, which gave rise to the city of Sonoma, in the valley of the same name, an important wine-growing centre ever since, north of San Francisco Bay. Sonoma was the site of the first American citizen uprising against Mexican rule in 1846. It is the northernmost mission of them all.

1821. Mexico completes its independence from Spain, retaining what was called Alta California as a “territory”, not just another Mexican state, with its capital at Monterrey. Its territorial boundaries were different from those of today. It ended almost 280 years of Spanish presence on the California coast (from 1542), although in its first phase the presence was not permanent, but sporadic but repeated. The last half-century (1769 to 1821) was the period of permanent and more extensive presence.

1826. First American to reach California by land: Jedediah Strong Smith, fur trapper. Reached San Gabriel Mission (east of present-day Los Angeles).

1828. Settlement by US citizens begins – very slowly.

1840s. Americans (in the East and Midwest) begin to receive information about the Far West from early literary accounts.

1846 a 1849. In 1846, the general war between the US and Mexico began, with the former annexing what was to become the state of Texas, which had belonged to Mexico. US naval forces in northern California and some American immigrant communities rose up in Alta California (Sonoma Valley) in June 1846, achieving victory in January 1847. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ending the war as a whole. Between 1846 and 1849 California was governed interim by a U.S. military Governor.

1850. California is hastily admitted to the United States of America as the 31st state.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021