Source:carlosdelriego

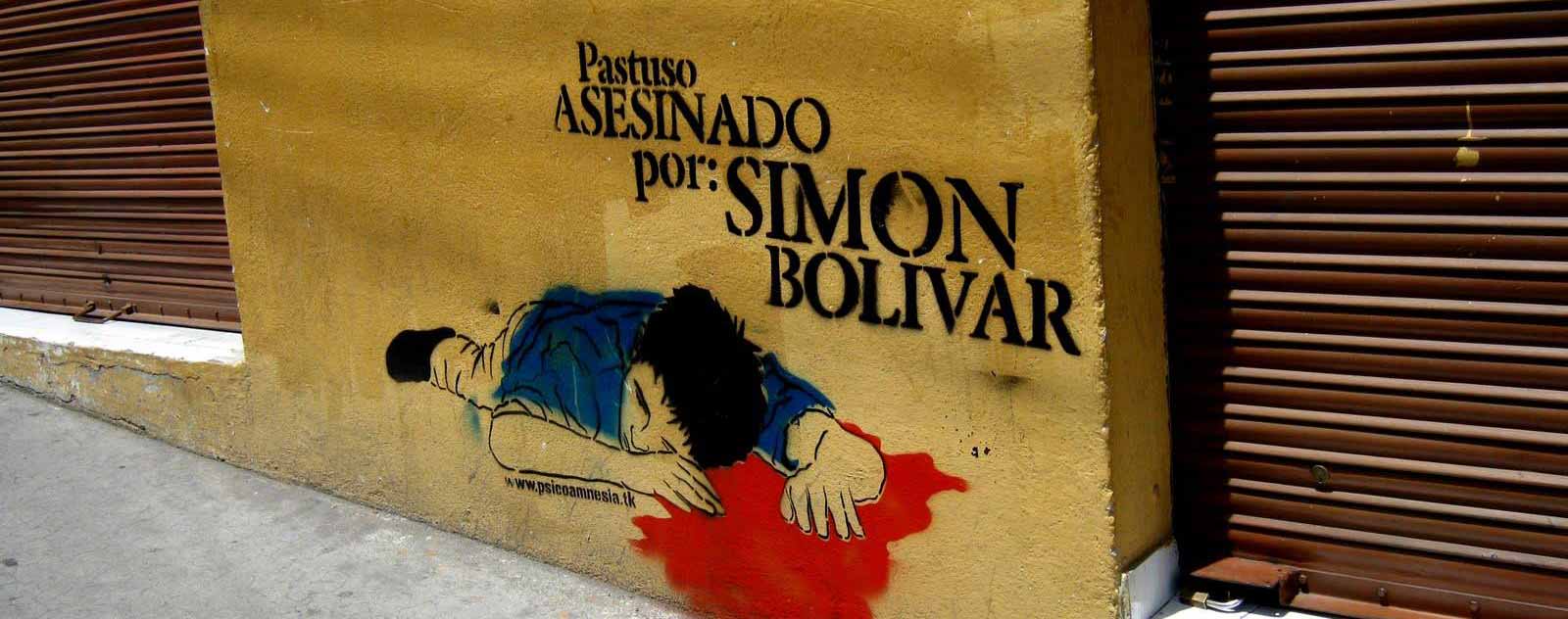

The memory of the Black Christmas massacre remains in the lands of Pasto.

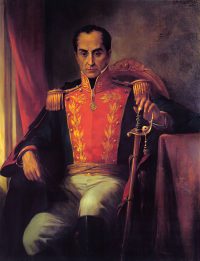

Attacks on statues and other symbols of the Spanish presence in the Americas are once again taking place, most recently in Colombia and Mexico (curiously, they do not disown the universities, hospitals or cathedrals built during the viceroyalty). And almost always this indigenist fury has Simón Bolívar as its hero, as a deity whose dogma is not questioned. However, ‘The Liberator’ deeply detested the Indians, as his letters and episodes such as the so-called “Black Christmas” show.

Probably the best known historical figure with the best position in the collective imagination of South America is Simón Bolívar, whose name is often taken as the ultimate indigenist and anti-Spanish ideological reference. But Bolívar himself makes it clear in his letters what his concept of the Indians was, and history shows the ways of the “Lliberator”, as happened on 24 December 1822.

After the war against Spain was over, Bolívar corresponded frequently with his English friends. In one of these letters he wrote: “Of all countries, South America (sic) is perhaps the least suitable for republican governments because its population is made up of Indians and blacks, more ignorant than the vile race of the Spaniards, from whom we have just emancipated ourselves”. In others he describes the Indians as “… thieves, ignorant and deceitful, lacking in moral principles to guide them. They needed others to rule and decide for them”. It is contradictory and servile for the descendants of those “thieves, ignorant and deceitful” to venerate the one who so despised them.

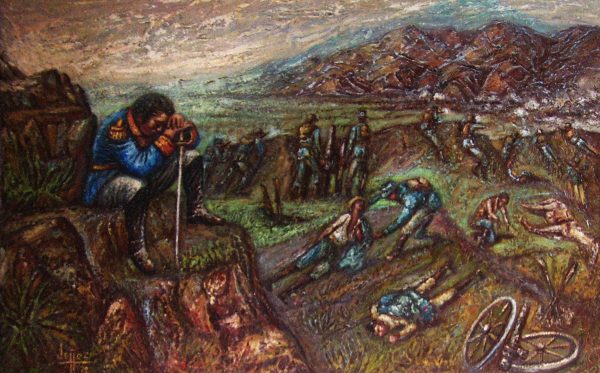

Symbolic composition of the Battle of Bomboná, made in spatula by José E. Ordoñez. Collection of the “Juan Lorenzo Lucero” Museum of Nariño History. (Pasto, Nariño)

But Bolívar did not stop at words. The inhabitants of Pasto (today a region of Colombia) remained loyal to Spain even after the war was over. Thus, throughout 1822, the Pasto guerrillas inflicted several defeats and damage on the criollo troops. Bolívar then declared a “war to the death” on the city of Pasto. It was in this context that one of the region’s heroes emerged, the Hispanic Indian leader Agustín Agualongo, still today remembered with admiration and respected by blacks, Indians and mestizos in the area.

According to specialist Felipe Arias: “In that conflict, there were both royalist and pro-independence indigenous communities, just as there were Americans, Creoles, blacks and mestizos. In Pasto, there was opposition to independence because it implied the disappearance of a monarchy that protected their collective properties from the historical abuses committed by the Creole landowners who sympathised with the republic”. In other words, many Indians saw that, contrary to the new constitutions, Spanish laws protected them against the powerful local elite.

In a letter to Francisco de Paula Santander, Bolívar put it bluntly: “Because you must know that the Pastusos (…) are the most demonic devils that have ever come out of hell. The Pastusos must be annihilated and their women and children transported elsewhere, giving that country to a military colony. Otherwise Colombia will remember the Pastusos when there is the slightest uproar, even if it is a hundred years from now because they will never forget our ravages, even if they are too much deserved”. This was and is the Bolivarian ideology: the extermination of the disaffected.

Thus, on 24 December 1822, General Antonio José de Sucre’s troops, following the liberator’s orders to the letter, exterminated the population of Pasto in an episode known as the “Black Christmas”. Shortly after the battle began, the Pastos surrendered en masse, but the Bolivarian soldiers showed no mercy, as the order was “war to the death”. According to a programme broadcast in Colombia in 1970 under the title Colombia Yesterday, Colombia Today, “they took ruthless revenge. Some surrendered, others wounded, all were killed. Whole families disappeared. They entered the church of San Francisco on horseback and killed all the asylum seekers, including women and children”. Nearly half a thousand fell in the first onslaught. Later, more than a thousand Pastusos were forcibly conscripted and sent to Peru and Ecuador. In Bolívar’s words: “The men who do not present themselves to be expelled will be shot, and those who do present themselves will be expelled”.

Excesses, violence and forced recruitments continued in the area for years. The intention was to totally depopulate the town and the region and for the shameful episode of the “Black Christmas” to be forgotten; however, this collective memory is not only not forgotten but is reinforced over time.

Even so, much of the population of South America, including the indigenous people, will continue to hold Simón Bolívar as the great liberator of the Indians.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1552 Battle of Bicocca.

- 1565 Miguel López de Legazpi founds Cebu as Villa de San Miguel.

- 1806 María Cristina de Borbón Dos Sicilias was born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021