Source:Sociedad Geográfica Española

“In the interior of these sierras dwell a people called Botthant. They never wash their hands and give as their reason that something as clear and beautiful as water should not be soiled. They are thick white men, not very tall in body, they fight on foot and have no king among themselves. They live by making felt and come to sell it to a town on this side called Negarcot: and they come down in June, July, August and September; outside these months they cannot come because of the snows…”

The text above is the first description that the West has of Botthant’s country, the mythical Tibet. Its author is Antoni de Montserrat, a Spanish Jesuit born in the catalan town of Vic, who had the early privilege of travelling the vast Indian territory on elephant back as part of the military campaign of the Mughal King Akbar. His observations and his pen would give rise to an exhaustive account of the geography, culture and social organisation of the territories he visited. And then some. Montserrat has bequeathed to posterity the first known map of the area, but let us move on.

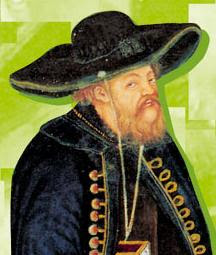

Antonio de Montserrat

Who was this hybrid of missionary and explorer and how did he reach the ends of the world described by Marco Polo? Antoni de Montserrat was born in 1536 in Vic, when there was not much of the world left to discover, into a Catalan noble family. As a student in Barcelona, he came into contact with the Society of Jesus, and in particular, it is believed, with Saint Ignatius of Loyola, which was to have a significant impact on his missionary vocation. Montserrat joined the Society, was ordained a priest in Portugal at the age of twenty-five and during the exercise of his priesthood in Lisbon, he unequivocally expressed his interest in travelling to the overseas missions, especially to those on the Asian continent, with which he maintained epistolary contact.

His first opportunity came in 1574, when, together with 39 other Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish Jesuits, he was sent to India, to the then Portuguese colony of Goa. He was thirty-two years old, had been in the Society for eighteen years and a priest for twelve. In the document “Catalogo dos Padres e Irmaos de Companhia de Jesus que forao mandados hà India Oriental, Anno 1574”, there is a brief curriculum vitae which, in a way, from that moment onwards would direct his steps: “Specialist in logic and cases of conscience, and special talent for his fellow man”.

There is no doubt that this “special talent” is what the leaders of the order valued when, five years later, the Society of Jesus received an unusual proposal from the Great Moghul Akbar, requesting the presence of Christian priests at his court in Fatehpur Sîkri. Akbar was driven by the impulse to know all the religions of the world, but the Jesuits deduced, wrongly, that the Mughal king wanted to convert to Christianity, and quickly chartered an expedition to instruct the monarch in the Gospels. Rodolfo Acquaviva, Francisco Henríquez and António de Montserrate were chosen. Their journey to the court would take them through such unknown lands as the Indian Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountain range. Along the way, Montserrat took notes of everything that happened to them, including curious descriptions such as that of the regulus, a dangerous reptile that lived in the jungle, which the Jesuit said “kills with the look in its eyes”.

The great mission

Acquaviva and Henriquez arrived at Fatehpur Sîkri on 27 February 1580. Montserrat, ill, would take another week to arrive at the magnificent Red Palace. The Jesuits offered the Great Moghul as a gift the eighth volume of the Polyglot Bible published in Antwerp between 1568 and 1573, whose illustrations captivated the monarch and were received with great affection. They stayed in the city for a year, during which time they studied Persian, the court language, and engaged in endless religious debates with their Islamic and Hindu opponents, which led to a close friendship between the Jesuits, King Akbar, and his right-hand man, Abu-l-Fazl.

An early version of the seal of the Society of Jesus (Church of the Gesù, Rome). The trigram “IHS”, comprising the first three Greek letters of “ΙΗΗΣΟΥΣ” (Jesus).

The Great Moghul’s esteem for Montserrat becomes clear when he appoints the priest as tutor to his son Murad, and is confirmed when he asks the Catalan Jesuit to accompany him on his military expedition to Afghanistan, which interrupts the placid debates at court. Akbar embarks on a long journey to put down the uprising of his half-brother, Mîrza, who has rebelled against his authority in the Bengal area, supported by some Afghan leaders. Antonio de Montserrat, the spontaneous chronicler of the expedition, takes advantage of the occasion to record it in great detail in his notebook, which will provide an alternative view to the official sources of the time and, above all, a first-hand experience of situations never before observed by Western travellers: “The king keeps a large number of elephants in his camp, using them for transport and battle. (…) they are trained to fight (…) For three months of the year the males become so violent that they kill their handlers (…) Once they calm down, they are enraged by adding tiger meat to their food”.

The Jesuit Montserrat followed King Akbar and his military campaign on his elephant for hundreds of kilometres, crossing the five rivers of the Punjab region and crossing the Indus, into the rougher Central Asia, Afghanistan. The military expedition would continue throughout 1581, advancing northwest into the territories of Pakistan, travelling through Delhi, the Punjab and the southern foothills of the Himalayas, and coming into contact with the people of Tibet and Kashmir. His commentaries on the Tibetans would be the first we find in the West since the time of Marco Polo in the 13th century, and the majestic mountain range would attract the Jesuit’s attention to such an extent that he devoted considerable effort to detailing its mountains and deciphering their names. Montserrat did not use earlier sources, but his own powers of observation, probably along his various journeys, to produce what would be considered the first recorded map of that part of the world.

In Jalalabad, the Jesuit would abandon Akbar’s troops, who would continue their march until the conquest of Kabul and, aware that the Mughal monarch had no real intention of embracing Christianity, he decided to return to Goa, where he would arrive in September 1582. It is in the beautiful Indian city where Montserrat decides to compile the notes taken during her stay with King Akbar. This would give birth to a short travel account, “Relaçam do Equebar, rei dos mogores”, which she would send to the General of the Company in the form of a letter.

A hectic writing process

Between 1582 and 1588, Montserrat undertook a more ambitious work: the compilation of the notes of his travels in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, in a more extensive and detailed work written in Latin, “Mongolicae Legationis Commentarius”. However, the writing of this work was interrupted by the request of King Felipe II to travel to Ethiopia to comfort two elderly Catholic priests. The trip itself seems to be an excuse to establish contact with the Abyssinian emperor and to sound out the possibility of bringing Coptic Christianity closer to the Church of Rome. He is accompanied by a young Jesuit from Madrid, eager and inexperienced, who admiringly describes Montserrat as “very intelligent for these things and with a singular grace for dealing with these kings”. He is Pedro Páez. His name, unknown at the time, would later be forever associated with the discovery of the source of the Nile.

The Jesuits, characterised as Armenian traders, decided to sail to the Strait of Hormuz to continue overland through Iraq, Syria, and Egypt in order to avoid the pirates of the Indian Ocean. However, their plans were cut short and they had to sail along the coast of present-day Oman via the frankincense route. When they landed in the port of Dhofar, the Arab captain of the ship they were travelling on reported them to the port commander, who decided to take them prisoner and hand them over to the Sultan of Hadhramaut, who lived in an isolated region in the interior of Yemen. They arrived there, in the city of Haymin, after an arduous journey, captive in a caravan of camels. Despite the arduous journey, Pedro Paéz seems to have enough strength left to savour an aromatic infusion that the ruler’s brother offers them in his palace. They called it “cahua, water boiled with a fruit called bun and drunk very hot, instead of wine”, he would later write. It was a drink still unknown in Europe, coffee.

After four months in prison they were suddenly released, recovering all their belongings, including the valuable manuscripts Montserrat was working on, which had threatened to be lost forever. However, after their arrival in Sanaa, after a gruelling journey of weeks on camelback through desolate lands, never before trodden by any European, the governor decides to imprison them and demand a ransom of twenty thousand ducats for their freedom. A long captivity begins in which they suffer great calamities, are chained in shackles and fed only with dry bread. It was in these precarious conditions, in January 1591, that Antonio de Montserrat finished the first version of his original manuscript.

In 1595 the Jesuits were again transferred to the port of Mokka (Yemen), but not to be freed, but to serve as oarsmen on two Turkish ships, chained in galleys. It was not until 1596 that a ship arrived from India with a ransom of 1,000 ducats to buy the freedom of the two priests. The governor accepted the payment and in August 1596, the two returned to Goa. Seven years have passed since their departure from Goa.

Paez recovered from the hardships of captivity and in 1603 he was able to realise his dream of entering the lands of Ethiopia. He would eventually build a church in Górgora, on the shores of Lake Tana, and was buried in the ruins of its main chapel on 25 May 1622, next to the source of the Blue Nile. His mentor, Antonio de Montserrat, would never recover; fevers killed him on the island of Salsete in March 1600, the same year in which he completed the definitive version of his work “Mongolicae Legationis Commentarius” and, together with it, the definitive design of his map of the Himalayas, a true cartographic jewel measuring 18×11 cm. and covering a large part of India and large areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan. It shows more than two hundred place names, geographical features highlighted in different shades, and geographical coordinates, reflected with surprising precision, which have the equator as a reference, drawing the line of the Tropic of Cancer with complete accuracy. In addition to the Himalayas, other mountain ranges can be distinguished in the northern part of the map, whose layout seems to coincide with the Karakorum, the Hindu Kush, the Parir and the Sulaiman Mountains. The accuracy of the small map is such that it would remain relevant until relatively recently, due to the detail and accuracy of its descriptions.

In the written chronicle, his texts reliably reflect all those details that are transcendent in the eyes of a Westerner: the geography, history, culture and religion of the different communities he has known, but also one of the great obsessions that moved the Christian religious to enter the vast Asian expanses: the search for ancient lost Christianities, the trace of the expansion of Christianity towards Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and the Far East. Encouraged by the chronicles of medieval travellers describing Orthodox, Nestorian, and Naiman communities, as well as the existence of the Coptic, Abyssinian, Armenian and Maronite churches, Rome desperately sought evidence of the existence of an empire that straddled history and legend, an empire led by a mighty priest-king, defender of the Christian faith in the face of Muslim advance, the reign of the Ethiopian Prester John.

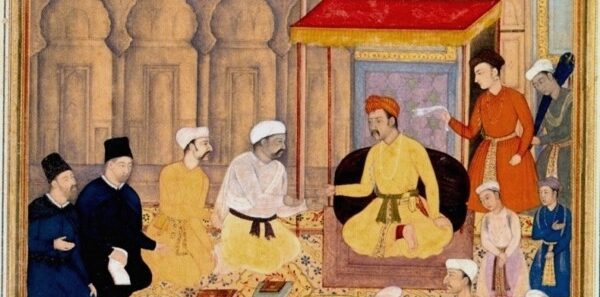

The Mughal emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad the Great (Arabic: Akbar) holds an inter-religious assembly in the Ibadat Khana at Fatehpur Sikri. The two men dressed in black are the Jesuit missionaries Rodolfo Acquaviva and Francisco Henriques. Illustration of the Akbarnama, miniature painting for Nar Singh, ca. 1605.

It would be a year after Montserrat’s death, in January 1601, when the Jesuit Antonio de Andrade would arrive in Goa with the aim of establishing a mission or searching for the Christian heritage in that mysterious isolated kingdom called Bottan or Tebat, which suggests that Montserrat’s chronicle was taken into account by the Order’s leaders. It makes one dizzy to think that the Great Mogul Akbar did not even suspect that the Jesuit’s journey and his writings had such a transcendental significance for the West. Somehow the emperor’s invitation to the religious would open the door to the discovery of one of the last spaces to be conquered by the champions of the Christian faith, but also by the travellers of that incipient Renaissance Europe.

A forgotten manuscript

And yet, after that first impact, the Montserrat work suffered a life as eventful as that of its author. Suffice it to say that most of his writings remained anonymous for three centuries. The manuscript “Mongolicae Legationis Commentarius” was not discovered until 1906 by the Rev. W.K. Firminger in the library of Saint Paul’s in Calcutta. It was a small treasure consisting of 140 manuscript leaves and a tiny map of India. Until then, neither the academic nor the ecclesiastical world knew about them. Three years later, the Jesuit Van der Vergel received the manuscript and showed it to the Belgian Father H. Hosten, a scholar of the Catholic missions, who, aware of the importance of the work, deciphered the calligraphy of Montserrat and made a transcription which he published in its original Latin version in 1914 in the magazine published in Calcutta “Memoirs of the Asia Society of Bengal”, to later translate it into English and publish it in various issues of the magazine “Catholic Herald of India”.

Today, in the 21st century, the Jesuit’s work is reaching its rightful place thanks to the popular publication of his works, translated from Latin into Catalan and Spanish by the orientalist Josep Lluís Alay. His growing fame has even led to a series of reports on Catalan television and the creation of a scholarship for the study of Asian science and culture. But what happened to the original manuscript in the three centuries between its author’s death and its first appearance? Seals and annotations show that it would have passed through three British libraries in India before reaching the Anglican cathedral in Calcutta. But these records date back to 1800, so we still do not know what happened between 1600 and that time. It is likely that, hidden in the archives of the Society of Jesus – dissolved in the intervening years – it wandered from drawer to drawer for two centuries, immersed in its own journey.

At least we can be grateful that it has not been lost forever, as is the case with four other manuscripts written by Montserrat on the customs and geography of India and Central Asia. The mystery of the whereabouts of the Catalan Jesuit’s enormous work remains a mystery to this day. But who knows? Perhaps someone in a library or in the forgotten archives of a church in India, England or Portugal will at some point come across the priest’s tight handwriting and fate will allow us to recover the rest of his stories, to discover a not so distant past of the surprising and captivating Asian continent, and of the foothills of that fabulous and millenary India, which Westerners were contemplating for the first time with their own eyes

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021