Source:ABC

It is estimated that between 10,000 and 12,000 soldiers were captured, many of whom were mistreated by the rebels despite the Geneva Convention and the passivity of the United States. “In Cavite Viejo there are more than 5,000 of them, living in huddles, sleeping on the floor, naked, men, women and children mixed together. The atmosphere is unbreathable”.

The news published by the “Heraldo de Madrid” on 9 December 1898. must have shocked the thousands of Spanish families who had seen their sons and husbands leave for the other side of the world and had no news of them. “This morning we spoke to an army chief who was telling us about the Philippines, from where he recently returned. The story we heard was a horror, a real horror. We think we know something of what is happening in our former colonies, but as soon as we talk to a witness, we realise that we don’t know everything, because we don’t know the most painful, the saddest things”.

The Philippines had come under Spanish rule when Miguel Lopez de Legazpi subdued Manila and undertook the occupation of the rest of the island of Luzon in 1571 with only 300 soldiers. Until the 19th century, the archipelago was Spain’s trading wedge in East Asia, but in 1896, pro-independence Tagalogs rose up against Spain through guerrilla warfare. Then came US support and we lost everything. Thousands of prisoners were left on the battlefield. “Among the Tagalogs there are 12,000 Spaniards. There are not, there were. Now there are not even three thirds of them left, because they have already succumbed to the knife, to hunger, to pain or to mistreatment. There is no cruelty comparable to that inflicted on those luckless Spaniards. Every day a handful of them die. If they are not rescued soon, not a single one will be left in Spain as a living example of the hatred and cruelty of Aguinaldo’s savages”, said this military commander interviewed by the Madrid nwespaper.

Data on the war in the Philippines, as opposed to Cuba and Puerto Rico, is scarce, despite the films and books that have recreated the siege of Baler, the naval battle of Cavite and the siege of Manila. The latter involved 8,500 American soldiers and 12,000 Filipinos commanded by the aforementioned Emilio Aguinaldo, who accepted the Americans’ deal in exchange for succulent promises, until he became the country’s first president after independence. Historian Jesús Flores Thies asserted in a 1999 study that it was not only longer than Cuba, but also bloodier. The lists published in the Official Journal of the Spanish War Ministry were very confusing. Historian David F. Trask estimated in “The war with Spain in 1898” (1996) that Spanish soldiers killed in combat there numbered 3,000, but only from the Army, not counting those who might have died in naval battles or during repatriation from diseases contracted.

“Every day costs us lives”

“In Cuba it is not the material pain that can kill our troops, it is the humiliation, the outrage and the shame suffered on a daily basis. The whole world has already learned from the telegrams published in the press how the Yankees are forcing twice as many soldiers on board as can fit on each ship. They do not pay us the slightest attention, nor do they recognise the slightest right. Some islanders, with no feelings and no loyalty whatsoever, join in this unmerciful work of mortifying our people. Can this go on like this?”, another Spanish army source consulted by the “Heraldo de Madrid” asked himself; he went on to reply: “Neither on one side nor the other, neither in the archipelago nor in Cuba, can things go on like this. Neither in the Philippines, because every day that passes costs the lives of our imprisoned compatriots, nor in Cuba, because each new day is marked by some new insult to our dignity, which has had enough of outrages”.

A month earlier, the correspondent of the London newspaper “The Star” had already borne witness to the barbarity caused by the Tagalogs. So outraged was he that he went to visit the American General Elwell S. Otis, the military governor of Manila, in search of a little humanity for the prisioners. The answer was negative, according to the article reproduced by some of the mainland media: “The Americans are showing the utmost barbarity in condoning the horrors committed by the Tagalogs on the Spanish prisoners. It is not possible to narrate what I have seen. The warmest imagination could not imagine the whole reality. Filled with indignation I went to visit General Otis and asked him for a little mercy. The general listened to me impassively and, when I had finished, replied: «Everything you have told me has been communicated to my government and I have orders to do nothing». This passivity is infamous”.

He went on to describe Dantesque scenes such as these: “In Cavite Viejo (Old Cavite) there are more than 5,000 Spaniards, who have been left to live in two churches and some houses without roofs or living conditions. They live there huddled together, sleeping on the floor, naked, men, women and children mixed together. The atmosphere is unbreathable. There are many dysentery patients who do not receive medical care. In a church I visited, a Spanish doctor who was a prisoner told me about the horrors of the sick. The Tagalogs ignore requests for medicine and the sick die without any help being given. In Old Cavite there was a pharmacy, but the Spanish pharmacist to whom it belonged was killed and his house burnt down. Deaths among the Spanish prisoners do not fall below 20 to 30 a day. I was told that there were 62 children and that they all died from deficiencies in food and from scabies, which has spread among the prisoners in an atrocious manner. The young women prisoners were subjected to the greatest abuse, three of them having died as a result of the brutalities of the Tagalogs. The Tagalogs often go on raids and steal whatever they can. That is why most of the prisoners are in the buff. I have been presented with respectable people, naked. It was embarrassing and would revolt the most indifferent”.

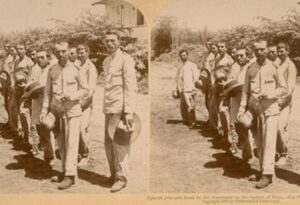

Spanish prisoners in Imus, Philippines | ABC

The first news of prisoners appeared after the sinking of the Spanish squadron in Manila Bay on 1 May 1898. A few days later, the insurgents took control of the provinces of Cavite and Manila. The capital held out for a little longer, but the conflict was rapidly spreading to the rest of Luzon, and the number of captured was increasing. The press reported on the negotiations for their liberation and sometimes even gave the names of those who had been lucky enough to return to Spain.

Luis Moreno Jerez, then editor of the “Diario de Manila”, published a book in December 1899, entitled “Los prisioneros españoles en poder de los tagalos” (“Spanish Prisoners in the Hands of the Tagalogs”), in which he blamed the Captain General of the Philippines, Don Basilio Augustín, for not having ordered the concentration of all the troops in the archipelago as soon as he learned of the break in diplomatic relations between Spain and the United States. By the time he finally gave the order, in late May 1898, it was too late. By September, the captured Spaniards numbered 9,000, according to figures reported in the “Heraldo de Madrid”. So many were concentrated in Cavite that Aguinaldo even ordered some of them to be transferred to the province of Bulacan.

In her article “Los prisioneros españoles en manos de los tagalos en el Diario de Córdoba (1898-1899)”, historian Patricia Hidalgo gathers various testimonies that reveal this mistreatment. “The Spaniards were stripped of everything they possessed […]. During the last months of 1899, aid was very scarce, and where it was given, it only amounted to half a lump of rice and four quarters”, said one of the chronicles in this newspaper.

Servants of the Filipinos

The rations were gradually reduced and the soldiers sent letters to their superiors demanding, without success, the back pay. Prisoners had to exercise public charity, serve as servants in the homes of indigenous people, cut firewood or fish to sell the produce in order to survive. Others opted to flee, but Aguinaldo’s government then decided to concentrate them in larger areas, subjecting them to painful marches on foot and barefoot.

“Manuel Sastrón, an official of the civil administration in Manila at that fateful time, emphasises the mistreatment of the Spanish captives: mistreatment, slapping, ingestion of putrid water and cannibalism, as well as forced labour for the repair and cleaning of squares, promenades and roads,” explains Hidalgo, who mentions other testimonies praising the good treatment they received. “They could well have been dictated by fear or be a true example of Stockholm syndrome,” he says.

It seemed that the situation might improve after the signing of the peace treaty in Paris on 10 December 1898, according to which Spain ceded sovereignty over the Philippines to the United States and the Americans undertook to organise the liberation of the Spaniards. But war broke out between the Americans and the Tagalogs, and things got complicated again. The testimony of one of the prisoners reflects this: “There was no doubt that our situation had become much worse. The most enlightened Indians recognised this, saying that the Treaty of Paris had closed all doors to give us our freedom, and that if the Americans tried to obtain it by force of arms, we would be exposed as cannon fodder and serve as barricades for the insurgent forces”.

After the signing of the treaty, the Spanish administration in the Philippines was closed. Efforts began to be made to free the prisoners. For example, the Red Cross and various Economic Societies of Friends of the Country sent various petitions to the government requesting that the wounded repatriates and prisoners of war be urgently attended to. The relatives of the captives formed the Association of the Families of the Prisoners in the Philippines and even published a newspaper, “Los Prisioneros”. However, many soldiers continued to return captive until 1902, three years after Spain lost the war. The Spanish government never knew exactly how many of them remained in the archipelago. Figures range from 10,000 to the 12,000 reported in the press. Many suffered this mistreatment despite the Geneva Convention of 1864, but the Philippine army was not yet internationally recognised in the war of ’98 and had not yet signed the convention.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1552 Battle of Bicocca.

- 1565 Miguel López de Legazpi founds Cebu as Villa de San Miguel.

- 1806 María Cristina de Borbón Dos Sicilias was born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021