Source:Libertad Digital

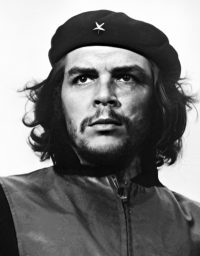

One photo is all it took to turn a psychopath into an icon of youthful rebellion and even the fight for, don’t laugh, freedom.

As some of us celebrate fifty years since the death of a psychopath who used ideology to channel how much he loved to kill (his words, not mine), parties with parliamentary representation in Spain still dare to celebrate his figure:

Hoy se cumplen 50 años del asesinato de Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara.

“Seguiremos adelante, como junto a ti seguimos…”#50siempreElChe pic.twitter.com/qp5LHhvcsH— Izquierda Unida? (@IzquierdaUnida) October 9, 2017

But who was Che really – an icon of rebellion or a psychopath? It seems reasonable to think that the best way to answer this question is to read carefully what the Argentinean communist said and wrote and then draw conclusions. We can start, for example, with his travel diary, which would be both romanticised and falsely portrayed in the hagiographic film The Motorcycle Diaries, and which included such racist passages as the following, which for some strange reason did not make it into the film:

The blacks, those magnificent specimens of the African race who have maintained their racial purity thanks to the little attachment they have to washing, have seen their royalty invaded by a new specimen of slave: the Portuguese. Contempt and poverty unite them in their daily struggle, but their different approaches to life separate them completely; the indolent and dreamy black man spends his pennies on any frivolity or on ‘sticking a few sticks’ [getting drunk], the European has a tradition of work and thrift that follows him to this corner of America and drives him to progress, even independently of his own individual aspirations.

His racism and that of other Castroist revolutionaries was reflected in the continuing discrimination that blacks have suffered under Cuba’s communist regime. And not only. He also organised the construction of the Guanahacabibes forced labour camp, originally intended for homosexuals and whose Auschwitz-inspired motto was “Work will make them men”, as recounted in the documentary Misconduct.

But that would come later. This is how Guevara described his first assassination in the guerrilla era:

I ended the problem by shooting him in the right temple with a [calibre] 32 pistol shot, with an exit wound in the right temple. He gasped for a while and was dead. When I proceeded to search his belongings, I couldn’t get his watch tied to his belt with a chain, so he said to me in a voice that didn’t tremble, far removed from fear: “Tear it off, kid, anyway…”. So I did and his belongings passed into my possession.

The hagiographers will insist on arguing that hey, that was a military necessity. But referring to that first assassination, Che wrote to his father in a letter: “I have to confess to you, Dad, that at that moment I discovered that I really like killing“. Very fitting for a T-shirt idol.

Anyone who wants to go beyond Korda’s photo knows that the first thing Guevara did after seizing power was to run a prison. In an appearance on TV Channel 6 in February 1959, Che declared that “in La Cabaña all the executions were carried out on my express orders”. There were several hundred executions in summary trials which were carried out, of course, with no guarantees of any kind for the condemned, which makes them pure and simple assassinations. In those days he told José Pardo Llada, who recorded it in his book Fidel y el Che, that “to send men to the firing squad, judicial proof is unnecessary. These procedures are an archaic bourgeois detail. This is a revolution! And a revolutionary must become a cold killing machine motivated by pure hatred“.

Incidentally, the same book contains a sentence by Che on freedom of the press that could have been proudly signed by Pablo Iglesias: “We must do away with all the newspapers, because you cannot have a revolution with freedom of the press. Newspapers are instruments of the oligarchy”.

The degree of Che’s fanaticism was reflected in his personal life. As Thomas de Quincey would say, one begins by murdering and ends by failing to be polite and putting things off until the next day. In one of the paragraphs of his July 1959 letter to his mother he wrote: “I am the same loner I was, seeking my way without personal help, but I have a sense of historical duty. I have no home, no wife, no children, no parents, no brothers, my friends are my friends as long as they think as I do politically“.

Some may think that, well, yes, he was a criminal and possibly a psychopath, but at least he fought for workers’ rights and for that he deserves recognition. Nevertheless, when he was already Minister of Industry, in a television address on 26 June 1961, he said: “Cuban workers have to get used to living in a regime of collectivism and under no circumstances can they go on strike“.

OK, yes, maybe he was not a trade unionist. But hasn’t his effigy become synonymous with peace? Maybe, but not because of what he did and said during his lifetime. In the aftermath of the missile crisis, the 21 December 1962 issue of Time carried his remarks to Sam Russell of London’s socialist Daily Worker, in which he regrets not having had the opportunity to unleash a nuclear war:

If the rockets [missiles] had remained, we would have used them against the very heart of the United States including New York. We must never establish peaceful coexistence. In this fight to the death between two systems we must win the final victory. We must walk the path of liberation even if it costs millions of atomic victims.

He never hesitated to defend his crimes publicly in any forum where he was heard, so it would be strange to understand the public adoration for him, unless ideology blinds them and makes them justify everything, as was the case with Guevara himself. For example, on 11 December 1964, during his second speech at the United Nations General Assembly, he said: “We have to say here what is a known truth, which we have always expressed to the world: Yes, we have shot, we have shot, we shoot and we will continue to shoot as long as necessary. Our struggle is a fight to the death.”

Since, in addition to all his personal shortcomings, Guevara was completely useless in any government work, Castro sent him on a guerrilla mission to both Africa and Bolivia, where he showed that he was not very good at that either. He was executed in the South American country on 9 October 1967, but that same year he left a sort of political testament in his message to the Tricontinental, an organisation dedicated to spreading communism. It was there that he wrote his famous phrase about creating “two, three, many Vietnams”, an endeavour in which he personally failed, as in all the others:

Hatred as a fighting factor, uncompromising hatred of the enemy, which drives beyond the natural limitations of the human being and turns him into an effective, violent, selective, cold killing machine. Our soldiers have to be like that; a people without hatred cannot triumph over a brutal enemy.

We must recognise that Che was at least sincere: he always recognised that the establishment of communism necessarily implied violence, although many today continue to deny it, despite historical evidence. On the first anniversary of his death, the Verde Olivo magazine he had helped to create published these edifying words:

The peaceful path is eliminated and violence is inevitable. To achieve socialist regimes, rivers of blood will have to flow and the path of liberation must be continued, even at the cost of millions of atomic victims.

This is the character that the left has idealised over the last decades because he looked handsome in a photo. The one who continues to populate the T-shirts of half the world. The one that Izquierda Unida continues to pay homage to time and time again.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021