Source:El cierre digital

The Duke of Béjar led the incursion of the Holy League army through the breach in the city wall of Buda in 1686.

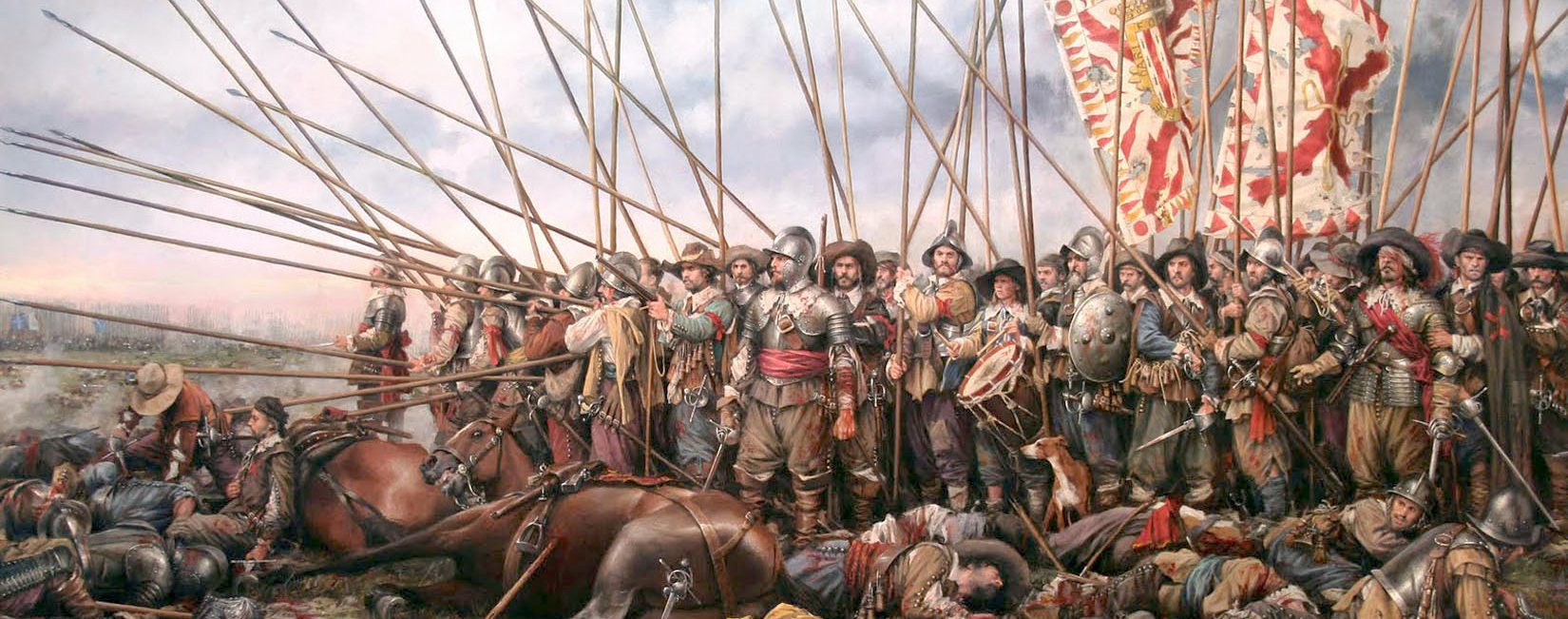

On 13 July 1686, a group of Spanish tercios led by Manuel López de Zúñiga led the incursion of the Holy League army through the breach in the city wall of Buda (part of present-day Budapest). It was the beginning of the end of the Turkish presence in the Magyar city, which was to fall for good two months later. Like many soldiers of the Hispanic Monarchy, Zuñiga lost his life in that assault.

This July marks the 334th anniversary of an episode of great historical importance that Spanish historiography has not always given a prominence commensurate with its magnitude. Christianity expelled from Buda the Muslim enemy, which began an accelerated retreat towards the East. Thus began the process of liberation of Hungary, one of the ancestral kingdoms of the Christian world. However, in order to reach this point, a series of circumstances had to take place in which the soldiers of Hispanic origin had a great deal to say.

Let us begin at the beginning. In 1453 Constantinople fell to the Ottomans. This event is considered a watershed in European history. According to many historians, it marked the end of the Middle Ages. In any case, over the next two centuries the Turks would constantly harass the eastern frontier of the Christian world, spreading their networks towards the Balkans and Central Europe. Along the way they would conquer, among others, part of the kingdom of Hungary. The situation became so serious that on two occasions they even laid siege to Vienna, the champion of European civilisation.

At the same time, a new power was rising in the West. The Spanish Monarchy, making use of a masterly marriage policy and seemingly inexhaustible economic resources from the New World, subdued its closest enemies one by one. However, its ability to stand alone against an enemy of similar potential, the Ottoman Empire, was limited. Thus, during the reigns of the Habsburg rulers, there were several attempts, promoted by the papacy, to mobilise Christian monarchs against the “heretic”. As the main Catholic power, the Hispanic Monarchy had to lead the fight, and it did so by placing itself at the head of a Catholic coalition, the Holy League.

Despite occasional victories by the League such as Lepanto, nothing changed: the Ottomans continued in their enterprise, trying to gain ground to the detriment of their western enemies. In 1683, they penetrated the Holy Roman Empire and reached the gates of Vienna. The Christians settled the situation with another alliance, which included the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire, the Principality of Moscow and the Republic of Venice. With the Turks defeated, the counter-offensive began. Pope Innocent XI launched an appeal to Christendom, which had the appearance of a last great crusade.

This is where our protagonist, Manuel López de Zúñiga, makes his appearance. The former Duke of Béjar was a member of the house of Zúñiga, a noble lineage of Navarrese origin. He had fought in the so-called War of the Reunions against France. In that conflict, he gained notoriety for his activity during the siege of Oudenaarde. According to Professor Emiliano Zarza Sánchez, his contemporaries identified him as “a knight, a bellator, who acted with loyalty to the monarchy in defence of the cross and for the spread of the true faith, a factor that made him an outstanding figure, appreciated and highly valued by his contemporaries“.

When he heard about what had happened in Vienna, he decided, according to some authors, for financial reasons (the finances of the ducal house were not at their best), to join the Holy League. He arrived in Vienna in June 1686, accompanied by a 12,000-strong army of volunteers from the Hispanic Monarchy. Some of them were veterans of the Flanders Wars, battle-tested tercios, but there were also colourful nobles hungry for glory and opportunists seeking fortune. The Christian army was able to muster a formidable force of around 100,000. This would not dampen the spirits of the Ottomans, who were well equipped behind their defences and had the lure of a substantial financial reward in the event of victory. They were also aided by the fearsome janissaries, an elite corps of mostly child war captives trained from an early age in the art of combat.

The siege was brutal and stalled from the early stages. At this juncture, it was Manuel de Zúñiga who broke the deadlock. He did so by personally leading his men in an encamisada, a military manoeuvre characteristic of the tercios, which consisted of attacking the enemy at night or at dawn, taking advantage of the element of surprise. His triumph earned him the respect of the entire Christian army. A few days later, on 13 July, the artillery of the Holy League managed to pierce the Ottoman wall. Zuniga and some 300 of his soldiers entered enemy territory first. Although the danger of the mission was obvious, at the time marching in front of the army was a matter of prestige and honour. In this sense, the tercios, the quintessential fighting units of the modern world, claimed this prerogative.

Thus Zúñiga and his men faced the fiercest resistance from the Turkish front lines. Zuniga was shot, which ended his participation in the battle and cost him his death days later. His body was initially buried in Hungary. However, it was soon claimed by his powerful brother Baltasar, who moved his remains to a chapel in Béjar. When the chapel disappeared, the tomb was moved to the cemetery of San Miguel, in the town of Salamanca. As for the siege, the Ottomans continued to resist until September. In their final defeat, the collaboration of the troops of the kingdoms of the Hispanic Monarchy continued to be fundamental.

Paradoxically, this feat has been remembered more in the Hungarian imagination than in Spanish. In the first third of the 20th century, a memorial was erected in Budapest, with an inscription that reads: “This is where the 300 Spanish heroes who took part in the Reconquest of Buda entered”. Be that as it may, this story is an indication that the Battle of Rocroi did not mark the end of the hegemony of the tercios, a message that, along with the increasingly contested ‘decline’ of the Spanish monarchy, the Anglo-Saxon historiographical tradition has successfully tried to convey.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1503 Battle of Cerignola (Italy).

- 1522 Santiago de Cuba is granted the city status by Carlos I.

- 1589 Margarita de Saboya is born.

- 1611 Archbishop Miguel de Benavides founded the University of St Thomas in Manila.

- 1777 José Primo de Rivera, Hero of the Sieges, was born in Algeciras.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021