Source:Fundación Disenso

The taking of Granada was the final chapter of al-Andalus, the Muslim socio-political construction that characterised the Medieval History of Spain.

In the General Archive of Simancas, in the so-called “Cubo de Felipe II” (where the most important documents of the royal heritage of the Crown of Castile were kept), the old inscription on a drawer reminds us that, among other important documents kept there, there can be found the “Capitulaciones con moros” (Capitulations with the Moors). It contains the set of documents relating to the Castilian conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada. Thus, the sovereigns of the Hispanic Monarchy never doubted the enormous historical significance of the so-called “Taking of Granada”.

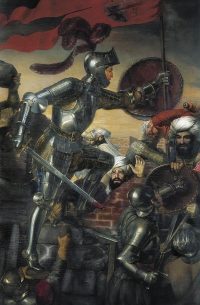

However, it can be seen how, from very early on, it was clear that the city of Granada was not “taken” in the sense defined by the Royal Spanish Academy, i.e. “conquest or occupation by force of a place or city”. In no case did we find a situation like the one that occurred in Loja (1486), where, after several particularly virulent encounters between the Castilians and the Nasrids, and after an intense bombardment of the town, the city surrendered. There followed hard, long and costly campaigns, with the participation of thousands of horsemen and labourers provided by villages and large towns of Castile, and with a major logistical effort at the service of the war apparatus; the results were the incorporations of Malaga (1487) and Baza (1489), after months of sieges, heavy fighting and significant human and economic losses. However, on the other hand, after the conquest of Baza, the subsequent collapse of the eastern fringe of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada (Purchena, all the places in the Almanzora region, the Sierra de Filabres, Almería, Guadix and the Cáceres area, Guadix and the Cenete area were surrendered without a fight) is explained by Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada with the theory that, after a show of force on the part of Castile, the afflexible policy of capitulations could attenuate the consequences of the conquest and hasten the end of the War of Granada1.

Thus, in addition to the usual concessions made by the victors (respect for life, property, religion and customs), generous conditions (such as, for example, unrestricted emigration to Africa) were negotiated in the east with the warlords who dominated this area: Cidi Yahya al-Nayyar and Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad az-Zaġall, called in the Castilian chronicles “El Zagal” (the Kid), cousin and uncle, respectively, of the king of Granada: Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muhammad ibn Abī il-Hasan’ Alī, better known as “El Chichito”, “El Rey Chiquito” or “Boabdil el Chico” (the small king). The Catholic Monarchs thus demonstrated how beneficial diplomacy could be to their interests within a framework of Nasrid political fragmentation.

The outbreak of the War of Granada (1482) was immediately accompanied by a civil conflict within the ruling dynasty of the Alhambra. The then King Abī il-Hasan ‘Alī (known as “Muley Hacen”), Boabdil’s father, became embroiled in palace intrigues led by Queen ‘Aisa, a powerful woman related to the nobility of Granada. The Arab chronicles tell us how the monarch’s wife encouraged the conspiracy against Muley Hacén when she and her son Boabdil found themselves relegated to the throne by the Christian harem slave Isabel de Solís. Regardless of the possible significance of these harem plots, the fact is that the Nasrid infighting was fuelled by them. The result was the temporary rise to power of Boabdil (July 1482), who came to control Granada and Almería, against Muley Hacén and his brother El Zagal, who had settled in Málaga. In an attempt to win a victory that would give him prestige, Boabdil plotted to penetrate Christian territory via the Cordoba border; the expedition ended in total failure (1483) and Boabdil was captured by the Christians. He regained his freedom only after declaring himself a vassal of Isabel and Fernando.

The years that followed, between 1483 and 1487, saw a complex dynastic conflict in Granada, due to which the return of Muley Hacen to the throne lasted only two years, as El Zagal deposed his brother in 1485, spurred on by his short-lived triumphs in Malaga against the Castilians. Boabdil recovered the Alhambra in 1487, taking advantage, in this case, of his uncle’s military setbacks against the Castilian arms. In the midst of this tangled panorama, the War of Granada continued and the Catholic Monarchs played their diplomatic trump cards on both sides, aware of the obvious weakening of their rivals. Thus, King Fernando the Catholic supported Boabdil against his uncle, helping him to settle in the eastern part of the kingdom under the promise of a peace that would protect all his subjects. A pact having been reached between the “small King” and El Zagal, and Boabdil having withdrawn to Loja, once the latter city had been taken, the sovereign of Castile reached a new agreement with the Nasrid to rekindle friction against his uncle once again. When the Catholic Monarchs finally marched on Granada, their hosts were joined by El Zagal, who became a vassal of Isabel and Fernando2.

In 1490, Granada stood as the last great Nasrid bastion. Clearly, the capitulation between Boabdil and Fernando at Loja should have put an end to the War of Granada; in fact, negotiations were entered into but were broken off, perhaps because of the Castilians’ lack of generosity towards the Granada king, or perhaps because of the latter’s position, willing to see the war through to its final consequences and hold out in his capital. Thus, in the spring of 1491, the rulers of Castile headed for la Vega de Granada at the head of a formidable army. The siege of Granada began.

The siege of the Nasrid capital was punctuated by various operations carried out by both sides from April 1491 onwards. Juan de Mata Carriazo describes the campaign as a series of chivalric, medieval-style episodes, in which the knights of Granada fought with the fearless courage of one who knows he has no way out and no possibility of receiving outside help, “while Boabdil negotiates and delays”3. The Castilian troops, with the efficiency that comes with superiority, set up a construction camp in the town of Santa Fe, after the fire had destroyed the one established earlier, a sign that they would not leave until the surrender of Granada. They also interspersed the felling in La Vega, the source of supply for the capital, with military actions, such as the one carried out at La Zubia, which led to the annihilation of what was left of the Nasrid cavalry. The famous Doncel de Sigüenza was killed in one of these rides. As a result, the besieged forces and army were depleted and, come winter, the shortages in the city became unbearable. An anonymous Arab author tells us that the citizens of Granada asked their king to enter into negotiations with the besiegers, as they realised that the latter intended to reduce them more by hunger than by force of arms. Little did the citizens know that their sovereign had already begun the preliminaries to a secret negotiation during the summer.

Talks for the capitulation of Spain’s last Muslim stronghold were slow. They were led by Fernando de Zafra, secretary to the Catholic Monarchs, on the Castilian side, and by Abū il-Qāsim al-Mulīh, vizier of Granada, together with the constable Ibn Kumāsa and the al-faqqiq Muhammad al-Baqqanī, known as “El Pequeñí”, on the Granada side. Even so, the sovereigns of both kingdoms intervened directly. Manuel González Jiménez states that, in the negotiations, the Christians must have mixed threats with promises and, of course, bribes4. The inhabitants of Granada made exorbitant demands, taking into account their weakened position, to which the Catholic Monarchs largely agreed, on the advice of their entourage, who were keen to speed up the surrender and make the necessary changes later on. Finally, on 25 November 1491, at Real de la Vega, the surrender of Granada was signed.

The capitulations for the surrender of the Nasrid capital are a set of documents of unequal importance, agreed with the Catholic Monarchs in reference to the city and kingdom of Granada, to Boabdil and his family, as well as to the main Granada negotiators.

The culminating document refers to the surrender of Granada, of which two versions are known: the one dated 25 November 1491, preserved in the Royal Heritage of the General Archive of Simancas, and the definitive one, dated 30 December, in the form of a Royal Privilege, which is in the Archive of the Dukes of Frías in the Historical Archive of Nobility in Toledo. Both differ on some points or introduce new articles. The essential difference is that the first version agreed to the surrender of Granada on the last day of March 1492, while the second text shortened the deadline to two months from 25 November. In any case, the two capitulations agree on the fundamental points: the people from Granada were guaranteed the preservation of their goods and property, their religion, their law (the Xara and the Sunna), their traditional authorities (alcadíes, alguaciles and almotacenes), their tax system (without requiring special services) and their freedom to emigrate to Africa or to return to Granada. The other point of special attention was the issue of the captives and the elches or Christian converts to Islam. With regard to the former, the liberation of all of them, both Christians and Muslims, was agreed upon. With regard to the Islamised Christians, it was decided not to force them to return to Christianity.

As for Boabdil and his family, the Catholic Monarchs recognised their immovable properties, both urban and rural, and the lordship of various tahas or districts in the Alpujarras region. The Nasrid king was promised 30,000 Castilian gold when the Alhambra was occupied and the freedom to leave for Africa whenever he wished, being able to take gold, silver or weapons with him, as was eventually the case.

The vagueness in the capitulations about the surrender of Granada was clarified by events. The Castilian pressures to occupy the city soon had been set out in the document of 30 December 1491 and were confirmed by the exaltation of spirits in Granada, which could jeopardise the fulfilment of what had been agreed. On 1 January 1492, secrecy had to be imposed in the face of certain attempts at revolt in Granada, both for the surrender in Santa Fe of the Nasrid hostages agreed in the capitulations and for the entry of a Castilian contingent into the city, captained by Gutierre de Cárdenas, Commander Major of the Order of Santiago and a man trusted by the Catholic Monarchs, the purpose of which was to occupy an Alhambra that had already been vacated.

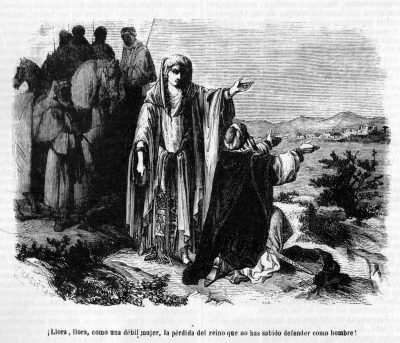

As Luis Suárez Fernández rightly points out, the surrender of Granada followed a previously agreed and pompously executed ritual6. It was midday on 2 January 1492. The Catholic Monarchs made their way to Granada from their royal residence in Santa Fe, at the head of a spectacular procession. At three o’clock in the afternoon, the sovereigns of Castile met Boabdil’s entourage on the sandy Genil River. The licentiate Rodríguez de Ardila reports that:

(…) the Moorish king arrived where King Fernado was and, approaching him, took off his turban and removed his foot from the stirrup, as it was agreed. King Fernando told him not to get off. He went further and kissed him on the arm, and gave him two keys to the main gates of the Alhambra, and said to him in his own language: “God loves you very much; these are the keys to this paradise.”7

Meanwhile, in the Alhambra, according to a letter addressed to the Lordship of Venice by an eyewitness to the events, “a herald of arms, placed on the tower, in a loud and clear voice, shouted: “Santiago, Santiago, Santiago; Castile, Castile, Castile; Granada, Granada, Granada, Granada. By the very high and very powerful lords Don Fernando and Doña Isabel, King and Queen of Spain, who have won this city of Granada and all its kingdom by force of arms from the infidel Moors, with the help of God and of the glorious Virgin, His Mother, and of the blessed Apostle Santiago, and with the help of our very holy father Innocent VII, help and service of the great, prelate knights, noblemen and communities of their kingdom!”. The herald’s announcement was followed by the sound of trumpets and bugles, and the roar of lombards and cannon8.

The capture of Granada had a considerable international echo. Celebrations were held in Rome and Naples, while Venice and England rejoiced at the capture of the last Muslim enclave on the Iberian Peninsula. Christianity experienced the event as revenge against Islam for the defeat it had suffered forty years earlier following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans (1453). Julio Valdeón Baruque refers to a revival in the spirit of Crusade, with a Christian military escalation in North Africa and the revival of the old dream of returning to Jerusalem the sign of the Cross9.

The Nasrid kingdom of Granada disappeared as a political entity, but it had a social extension through the Mudejars (Muslims living in Christian territory) first, and later the Moriscos (converts from Islam). While a large part of the nobility of Granada emigrated to Africa, where some of them founded the city of Tétouan, many notables and political personalities converted to Christianity to maintain their socio-economic position and as a result of agreements with the Castilians, which ensured them a place in the local oligarchy of Granada. The majority of the population maintained their roots and the socio-cultural aspect that characterised Granada for decades.

Predictably, the Castilian administration was unable to maintain the integrity of the respectful clauses that had been agreed with the people of Granada. Fiscal and socio-religious pressures soon began, and there were even cases of coercion and violence against the defeated. The Mudéjars of Granada, for their part, encouraged the tense situation by collaborating with the Muslim pirates who harassed the coasts of the kingdom of Granada from Africa. The conflict came to a head with the Mudejar revolt that opened the 16th century and led to forced conversion, and with the War of the Alpujarras (1568-1571), which ended the presence of any Nasrid remnants with the expulsion of the Moors from Granada.

The capture of Granada marked the final chapter of al-Andalus, the Muslim socio-political construction that characterised Spain’s medieval history. As a result, few events have been the subject of greater controversy, from Historiography to Literature and Politics, as their interpretation has swung from the glorious culmination of the Reconquest to the sad conclusion of a brilliant Andalusian past. Future generations will undoubtedly continue to revisit the events of 2 January 1492 in Granada for a long time to come.

Notes

- Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada (1964): Milicia y economía en la guerra de Granada. El cerco de Baza, Valladolid, Universidad de Valladolid, p. 101.

- Francisco Vidal Castro (2000): “Historia política”, en El reino nazarí de Granada (1232-1492). Política, Espacio, Economía, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, pp. 195-209

- Juan de Mata Carriazo (1969): “Historia de la guerra de Granada”, en La España de los Reyes Católicos (1474-1516). Las bases del reinado, la Guerra de Sucesión, la Guerra de Granada, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, p. 801.

- Manuel González Jiménez (2000): “La guerra final de Granada”, en Historia del reino de Granada. De los orígenes a la época mudéjar (hasta 1502), Granada, Universidad de Granada; el Legado Andalusí, p. 470.

- Miguel Garrido Atienza (1992): Las capitulaciones para la entrega de Granada (edición de José Enrique López de Coca Castañer), Granada, Universidad de Granada.

- Luis Suárez Fernández (2011): En los orígenes de España: mitos y realidades, Barcelona, Ariel, p. 257.

- Juan de Mata Carriazo (1969): “Historia…”, p. 888.

- Juan de Mata Carriazo (1969): “Historia…”, pp. 894-895.

- Julio Valdeón Baruque (2006). La Reconquista. El concepto de España: unidad y diversidad, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, p. 186.

- Ángel Galán Sánchez (2000): “Los vencidos: exilio, integración y resistencia”, en Historia del reino de Granada. De los orígenes a la época mudéjar (hasta 1502), Granada, Universidad de Granada; el Legado Andalusí, pp. 525-565.

- Rafael Gerardo Peinado Santaella (2019): El corregidor y el capitán: documentos sobre la represión de la resistencia musulmana en el Reino de Granada a comienzos del siglo XVI, Granada, Universidad de Granada.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1572 Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva founded the town of Guaduas (Colombia).

- 1578 Brunei becomes a vassal state of Spain.

- 1672 Spanish comic actor Cosme Pérez ("Juan Rana") dies.

- 1693 Painter Claudio Coello dies.

- 1702 The Marquis de la Ensenada was born.

- 1741 Spanish troops break the siege of castle San Felipe in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia).

- 1844 The Royal Order of Access to Historical Archives was promulgated.

- 1898 President Mckinley signed the Joint Resolution, an ultimatum to Spain, which would lead to the Spanish–American War.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021