Source:Somatemps

The results of the municipal elections of 12 April 1931, which triggered the departure of Alfonso XIII into exile and the proclamation of the Second Republic, remain a mystery. Now, 89 years later, the election results for the province of Seville have just been published, thanks to the exhaustive research of Professor Julio Ponce Alberca, from the Department of Contemporary History of the Faculty of Geography and History at the University of Seville, who has reconstructed the results.

In Seville, the monarchists swept the board, winning 966 councillors to 329 republicans. The elections were legal, but the protests in the streets ended up winning out over the votes cast at the polls and, two days after the elections, the Republic was proclaimed by revolutionary means, without respecting the legislation in force at the time.

When the monarchists went to react, it was too late. Once the provisional government had been set up, the Republic set in motion a machine to cloak itself in legality. The elections were repeated a month and a half later in the municipalities where the monarchists had won, and in the elections of 31 May, the monarchists only won five councillors to 981 republicans.

The departure of Alfonso XIII

Until now it was known that in the elections of 12 April the number of royalist councillors outnumbered republican councillors throughout Spain, and that the republicans won in most of the provincial capitals. These results were interpreted as a defeat for the monarchists to the extent that pressure was put on Alfonso XIII to go into exile long before the final results were known. As the proclamation of the Republic was rushed, the vote count was never completed.

Professor Ponce Alberca has gone to the original source and, after exhaustive research, has managed to reconstruct the results of these elections, village by village, district by district, in the province of Seville. He has published them in the book De las urnas a la república. Las elecciones municipales de 1931 en Sevilla (Published by the Provincial Council of Seville). The research has also brought to light some of the incidents that occurred in those elections and the irregularities that were committed afterwards.

In the 1931 elections, only men were called to vote (women were not allowed to vote until 1933). As they were held with open lists, voters had to write down the names of the elected candidates or use the ballots already printed by the parties to facilitate voting in a Spain with more than 30% illiteracy. The ballots were handed, without envelopes, to the president of the polling station, who placed them in the ballot boxes.

Four days after the vote, on 16 April, the proclamation of councillors and the election of mayors were scheduled. If there were any ties, they were to be resolved by drawing lots. The deadline for lodging appeals was eight days. A total of 309 councillors -most of them royalist- from 28 municipalities in Seville were automatically re-elected, without the need for a vote, as no other candidates had been presented in their municipalities. This was established in Article 29 of the Electoral Law of 8 August 1907.

Irregularities and incidents

On election day, voting was interrupted in the municipality of Gerena amid shouts of “Long live the Republic” and “Death to the King”, and in La Puebla del Río some agitators broke the ballot boxes during the counting of the votes. In Seville capital “there were sections that were not constituted on Sunday, the voting being postponed until Tuesday 14”, the day the Republic was proclaimed, and the councillors were sworn in without the count having been completed, says Ponce, who considers that “this does not detract from the legitimacy of that corporation, but it is difficult to deny the irregularities of the procedure”.

Wherever the Republicans won, “they took over the corresponding Town Hall without waiting for the ordinary process of taking office”. On the other hand, “in the localities where the monarchists won, it was almost impossible for the elected councillors to take office under pressure from the elected representatives of the (Republican-Socialist) conjunction”.

Revolutionary eruption

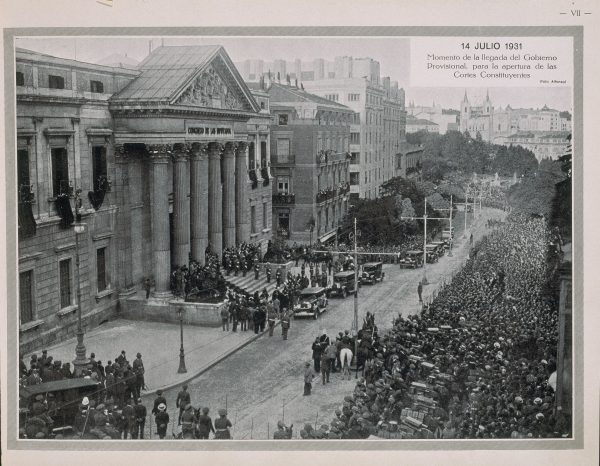

Moment of the arrival of the Provisional Government for the opening of the Constituent Assembly. April 14th, 1931

The fact is that on the morning of 14 April Spain was still a monarchy, but when the news began to spread that the Republican candidates had overwhelmed the monarchists in the main cities, many citizens took to the streets. In Seville, they gathered in the Plaza Nueva, and the ripple effect spread to other towns in the province. “The wave in favour of the Republic grew unstoppably from that morning, and by nightfall Spain had changed its regime”, says Ponce, who maintains that “the Republic’s emergence was revolutionary; its implementation and scope were not”.

The change of regime “did not fit into the legal framework in force in those days”, the professor explains, and recalls that, after the local elections, provincial elections were scheduled for May of the same year and general elections in June. “If the renewal of the provincial deputations and the Cortes had produced another Republican victory, the new government that emerged from the chambers would have been in a position to promote a referendum on the Monarchy. That would have been an orderly transformation. As we know, nothing of the sort happened, and the King left Spain without even abdicating”. In fact, what Alfonso XIII did was to suspend the exercise of royal power, in the hope of returning to Spain at some point.

However, the professor argues that “the lack of legality does not necessarily imply an absence of legitimacy”, given “the weariness that a large part of Spanish society showed towards the Monarchy and the worn-out political system of the Restoration”.

Reversing the situation

Obviously, there were sectors that pushed to try to reverse the situation. In these circumstances, “leaving numerous town halls in the hands of royalists was considered highly dangerous”, Ponce explains. “The solution came from a strategy that sought to cloak itself in legality”. A deadline was opened to deal with protests of alleged corruption and electoral irregularities: the protests would be accepted, and while they were being resolved, republican management commissions were appointed. The idea was to call new elections where irregularities had been detected and, “after the new elections, all town councils would be truly legitimate”. The theory was logical, but “the practical application was far from correct”.

On 16 April, the Minister of the Interior, Miguel Maura, sent a telegram to all civilian governments ordering the constitution of all elected town councils, except “where there were or are protests against their functioning”. Some protests were lodged after the elections, or even after the telegram, to prevent the constitution of monarchist town councils.

Electoral rerun

The Ministry of the Interior received complaints from 49 municipalities in Seville, but the elections were repeated in 80. “The avalanche of files and the material impossibility of analysing them made it advisable to hold new local elections”. “The elections were almost always repeated in those municipalities (and this was no coincidence) where the monarchist candidates had triumphed on 12 April” , Ponce says.

In this climate of hostility – between 10 and 13 May some 100 religious buildings had been burned throughout Spain in the famous burning of convents – some monarchists decided to withdraw from political life. A few persisted and others, a small percentage, opted to join “the winning bandwagon and change flag”. In Los Corrales, for example, the Monarchy disappeared, but the ex-monarchists kept the mayor’s office, according to the exhaustive study.

The basic source of Professor Ponce’s research has been the electoral documentation held in the archives of the Seville Provincial Council, where he has found the voting lists and the minutes of the scrutiny and proclamation of candidates, among other documents, some of which are incomplete. He also consulted the Official Bulletin of the Province of Seville, the ABC newspaper archive and the archives of the local councils.

Message to other researchers

Ponce includes a message to his colleagues in his book: “One of the aims of this work is to serve as a reference for other similar research carried out in other Spanish provinces. After what has been presented here, it seems advisable that they be carried out”. Perhaps one hundred years after the vote, the full results of a municipal election that changed the history of Spain may finally be known.

Source: ABC

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021