Source:Libertad Digital

The truth is that Malinche, like many native women, thanks to the Spanish enjoyed a respect and freedom that the Aztecs denied her.

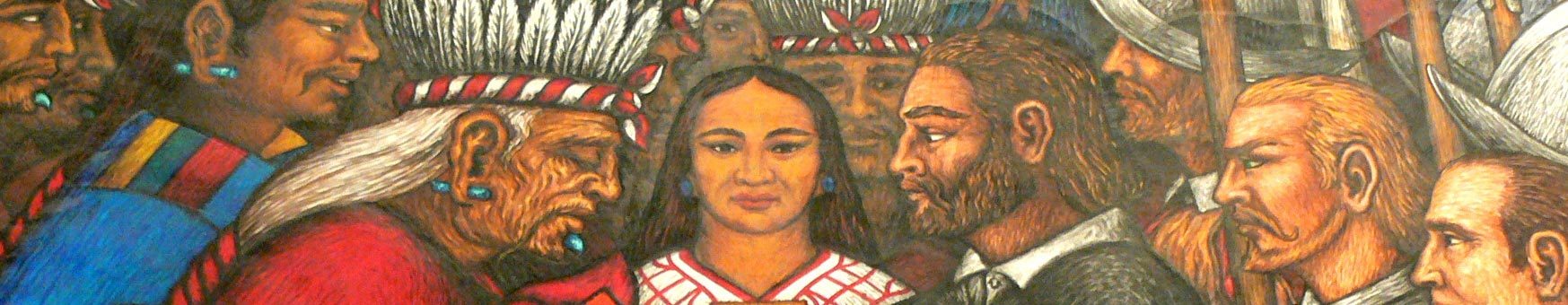

Two women were essential in the beginnings of the Spanish Empire. The Spanish Queen Isabel I of Castile, who supported Christopher Columbus’ audacious plan (as his calculations were erroneous), and Doña Marina, without whom the conquest of Mexico would have never been possible. Bernal Díaz del Castillo tells how the incorporation of the Aztec native to the expedition “was a great start for our conquest; and this way things worked out well, thank God, very prosperously. I wanted to declare this because we could not understand the language of New Spain and Mexico without Doña Marina”.

Her native name was Malintzin, converted into the Spanish “Malinche” and once baptized she went to be named “Marina”. Very little is known about the woman who became Hernán Cortés’ interpreter and adviser. We don’t have any handwritten documents from her, neither her thoughts on her amazing destiny nor the story of her life. The only references we have about her were transmitted by the Spaniards Díaz del Castillo and Francisco López de Gómara.

A gift for the Spaniards

Her parents were caciques but when her father died her mother married another man and she then was sold as a slave. After the Centla Battle on the 15th March 1519, the governors from the Tabasco region gifted their new lords’ jewels and twenty young women to serve them as cooks, laundresses, and concubines, amongst them was Malinche. She probably was between eighteen to twenty years old. She was baptized alongside the other women and she was named Marina, the name by which she entered history.

She soon became indispensable due to her command of the native languages, mainly the Náhualt and the Mayan, and her fast acquisition of the Spanish language. This way she replaced the other “tongue” (translator) of the expedition, Jerónimo de Aguilar. Marina not only became the interpreter but also Cortés’ adviser on the customs of the indigenous peoples of the Mexican Empire and its divisions.

According to López de Gómara, Cortés “promised her more than her freedom if she would speak the truths between him and those people as she could understand them, and he wanted her as his interpreter and secretary”. We can imagine to which extent Marina became so important due to her appearance in several codices alongside Cortés and also because she was honored with the respect accorded to Spanish women by calling her Doña Marina.

Marina’s services stood out during the battles where she translated the officers’ orders to their Tlaxcaltecan allies and also disseminating Catholicism; thanks to her, the Christian doctrines were introduced in the native languages for the first time. Hernán Cortés was a womanizer. It is known that he had eleven children by six women. Despite being married to Catalina Suárez Marcayda, he made Marina his mistress. When his wife arrived from Cuba this illicit relationship continued under the same roof, at a palace in Coyoacán.

In 1522, a mestizo baby was born. He was named Martín and years later he received, alongside his siblings Luis and Catalina, his legitimation by means of a papal bull. His father took him on his last trip to Spain in 1540, where Emperor Carlos V accepted him as a servant of Prince Felipe. The young man devoted himself to the army and fought in Germany, Algiers, and the Alpujarras, where he died battling under the command of Juan de Austria, another illustrious illegitimate son.

Cortés gave her a husband and two encomiendas

Fortune and honours did not constrain the Spanish conquerors to their palaces. Their passion for travel and discovery led them to search for new adventures. Hernán Cortés took Marina on an expedition to the Hibueras to assist him as an interpreter. Then, his mistress decided to marry a veteran captain of the Conquest, Juan Jaramillo, councillor at Mexico’s local government and wealthy messenger.

Although princes only marry servants in fairy tales, Maria enjoyed a marriage of quality and fortune. The wedding took place on the 15th January 1525 and her protector gave her two encomiendas. Why did he act this way? Perhaps a relationship with a former slave would have been an impediment for him to become a viceroy. Or maybe to attenuate the suspicions on his wife’s death being as the result of a passion crime in November 1522.

In 1526 she gave birth to a daughter that was named Maria. Doña Marina passed away between 1526 and 1527 in Mexico city, probably as the result of one of the measles or smallpox epidemics that spread through New Spain.

“Malinchismo”

The Mexican revolutionaries have tried to present her as a traitor to their society which actually degraded her to the status of slave and object. The term malinchismo developed as a term that, as recorded in the Dictionary of Mexicanisms by Guido Gómez de Silva means “a complex of adherence to the foreign while underestimating your own”. Others consider her a traitor. Iván Vélez, a current historian, defends her: “the enslaved girl, Cortés’ mistress, as per our thesis, could have not possibly betrayed a nation that, simply, did not exist”.

In reality, the real betrayers were probably those independentists who have reduced Mexico to a fraction of what it was. The Viceroyalty of New Spain in the XVIII century had borders to the east with China (Philippines), to the north with Russia (Nutka island), and to the west with Mississippi River and Florida. It controlled the Gulf of Mexico and was Europe’s link with Asia in the Pacific. Between independence (1821) and Venta de la Mesilla (1853) the Mexican republic lost the Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Central America (the Guatemalan headquarters of the military government), California, and all the territories north of Rio Grande.

The truth is that Doña Marina, like many other native women, enjoyed a degree of freedom and respect by the Spaniards that the native Aztecs would have never granted to her. She and many women of her time ceased being treated as trade goods and men’s property.

(Extracted from Eso no estaba en mi libro de historia del Imperio español (Spanish), by Pedro F. Barbadillo)

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021