Source:ABC

To make the vaccine resist during the crossing, the Alicante resorted to a score of orphaned children, in the absence of volunteers, who were passing the virus from one to another. The journey was not easy.

The Armed Forces have always been one of the few institutions in Spain that safeguard the common memory. For ensuring that people who have exposed their physical and mental integrity for the nation do not end up buried in tons of oblivion. Hence, the names of their units, ships, and operations always have space to honor the heroes of the past.

The latest example of this is Operation Balmis, the name that the Ministry of Defense has given to the military deployment to fight the spread of the Covid-19 virus. Balmis, in honor of the doctor Francisco Javier Balmis who spread the smallpox vaccine at the beginning of the 19th century throughout the world with the sole objective of saving as many lives as possible.

“In old age, smallpox”

Before this expedition around the globe, smallpox was a serious infectious disease characterized by the bumps it causes on the skin, hence its Latin name variŭs (varied, motley), and because it affects both rich and poor in childhood or youth. “In old age, smallpox”, the popular saying, is but a reminder that the disease used to strike especially with minors, leaving deep marks on the skin. Rare was the woman or man who had a smooth face.

Although the disease was not completely eradicated until the late twentieth century, the tools to combat and prevent smallpox were already created in the previous century. Several Spanish scientists are known, such as Pedro Manuel Chaparro, who during the 18th century successfully tested methods to inoculate the virus in Chile, Peru, and other corners of the Empire. However, it was the British Edward Jenner, known as “the father of immunology”, who went down in history for developing a scientific method of inoculation of smallpox after realizing that cow milkers did not contract the disease because they were exposed to the bovine version of the virus.

Jenner performing her first vaccination on James Phipps, an 8-year-old boy. May 14, 1796

Edward Jenner, considered one of the great scientists in the history of mankind, failed in his time, at the end of the 18th century, to make his method known beyond his people. The most Jenner could do was build a cottage in her backyard and vaccinate the neighborhood children in Gloucestershire. Nobody was interested in his vaccine or him until Francisco Javier Balmis started an inoculation throughout the Spanish Empire, which at that time was like saying worldwide.

This military man, who became Carlos IV‘s personal physician, had lived and worked in Havana and in Mexico, where he had first-hand investigated venereal diseases and the treatments that could alleviate their development. When Edward Jenner made his discovery of the smallpox vaccine known, Balmis was among his earliest supporters. On his return to Spain, he convinced this king and his ministers to promote an expedition that would spread, altruistically, the smallpox vaccine throughout the globe.

A virus carried by children

To ensure that the vaccine resisted during the journey, the Alicante resorted to a score of orphaned children, in the absence of volunteers, who were passing the virus from one to another. Among the twenty-two children (between three and nine years old) there were six from the Casa de Desamparados in Madrid, another eleven from the La Caridad hospital in La Coruña, and five from Santiago de Compostela.

The children were subjected to weekly inoculations, in two of them, with the liquid obtained from the pustules of those vaccinated the previous week. Balmis carried carefully prepared apparatus – thermometers, barometers, a pneumatic machine, thousands of crystals for pus smears … – as well as two thousand copies of the text on the vaccine that he had just translated and that was intended to be distributed free of charge for the purpose of to disseminate knowledge for the practice of vaccination.

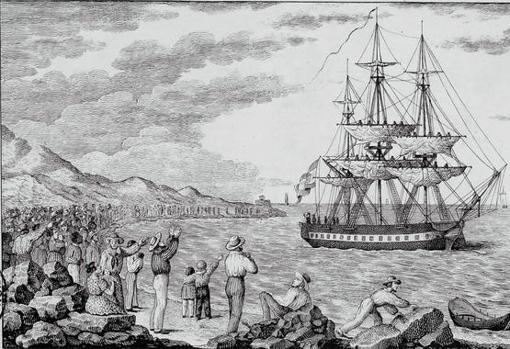

On November 30, 1803, the ship María de Pita set sail with 37 people from the port of La Coruña. The Royal Smallpox Vaccine Philanthropic Expedition consisted of Balmis, a prestigious surgeon; two medical assistants, two pilots, three nurses, and the rectoress of the Casa de Expositos orphanage in La Coruña, Isabel Zendal Gómez. The director was from Alicante; the deputy director, Dr. José Salvany, catalan; the nurse, Zendal, was from Galicia and the captain of the corvette was Basque.

El María Pita, navío fletado para la expedición, partiendo del puerto de La Coruña en 1803 (grabado de Francisco Pérez).

About this nurse, Balmis informed the ministers of Carlos IV that he had left a piece of her in every league:

“The miserable Rectoress who with excessive work and rigor of the different climates that we have traveled, completely lost her health, tireless night and day has poured all the tenderness of the most sensitive mother on the 26 little angels [those who made the trip to the Philippines] who is in their care, in the same way that he did from La Coruña and on all trips and has assisted them entirely in their continued illnesses.”

The ship toured Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Cuba and several cities in Mexico. Several doctors who were part of it took the vaccine to Texas in the north and Nueva Granada (Colombia) in the south, and finally reached Chiloé in Chile. The obstacles suffered by the expedition members were extraordinary: the trip began with a shipwreck at the mouth of the Magdalena River, Salvany became seriously ill and was left blind in his left eye before dying in the city of Cochabamba, in 1810, as a result of the harsh hardships that he had to suffer while fulfilling the mission of introducing the vaccine in the Andean mountain range. Most of the members of this sub-expedition would not return to the Iberian peninsula.

Trip to the pacific

The need for new children to transport the virus forced Balmis, given the refusal of the local authorities to facilitate orphans, to buy slaves, three women and the incorporation of a child, in Cuba. Many commanders and senior American clergymen ignored the expedition, believing that it was not an effective method against smallpox, although there was no shortage of middle commanders who helped vaccinate thousands of people in each port they visited.

Only one of the original twenty-two children died during the journey, while the rest were admitted to the hospice and were later adopted in Mexico. In September 1805 the expedition left America and sailed from Acapulco to Manila with 26 new children.

Bust of Francisco Javier Balmis in the Faculty of Medicine of the UMH in San Juan de Alicante.

The expedition vaccinated in the Philippines and even made several incursions into Chinese territory, mainly in the Canton area. Onboard the frigate Diligencia, Balmis, along with Francisco Pastor and three children, headed to Macao, suffering the consequences of a typhoon. That saved an undetermined number of lives and, as a secondary purpose, it obtained an extensive natural scientific study, especially botanical, of the areas where they were active as vaccinators.

The assistant Antonio Gutiérrez was in charge of returning to Mexico the twenty-six children they had brought to the Philippines. With serious financial problems to pay for the trip to Spain, Balmis received the help of an agent of the Royal Philippine Company of Canton, with the loan of the 2,500 pesos he needed. On his return to the island of Santa Elena, Balmis also introduced the vaccine there, in June 1806, and on August 14 he arrived at the port of Lisbon. On September 7 of that year, he was received by Carlos IV in San Ildefonso, who congratulated him on his work.

The scientist and popularizer Alexander von Humboldt endorsed that trip “as the most memorable in the annals of history”, while Edward Jenner himself, who became known worldwide with the expedition and with Napoleon’s decision to vaccinate his troops in 1805, wrote: “I cannot imagine that in the annals of history there is a more noble and comprehensive example of philanthropy than this”.

For the WHO this was officially the first international medical campaign.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1648 Pedro II of Portugal is born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021