Source:El Debate

These women sometimes fought more bravely than some of the men. While the men played cards or drank mead, they cared for the wounded and carried out a multitude of other duties as quartermasters

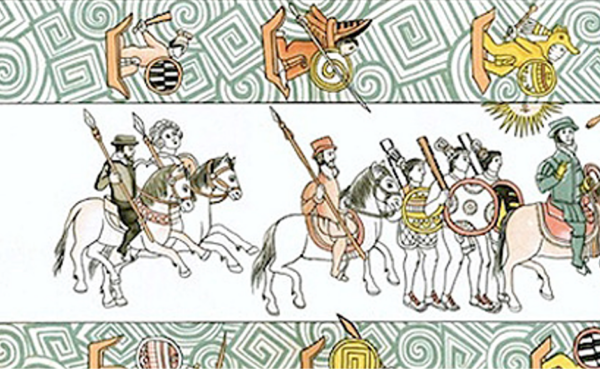

Despite the controversy that always surrounds the character, Cortés‘ voyage was so extraordinary and surprising that he has gone down in history as the “inventor” of Mexico, in the words of the historian Juan Miralles, a sort of “Betelgeuse”, that is, a star so bright and gigantic that it has always hidden other minor stars in the firmament of the conquest, now, five hundred years from the present day.

Beyond its lights and shadows, Cortés’ genius is undeniable, but it was a collective adventure in which many different people took part. Soldiers, carpenters, sailors, masons, even a couple of priests and a necromancer. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who always wished to emphasise this collective character in contrast to Cortés’ letters of relation, in which he did not spare himself, did not fail to highlight the role of the Spaniards and even of the allies, mainly Tlaxcalans, who accompanied him in this enterprise. Thus, characters such as Pedro de Alvarado, Cristóbal de Olid, Gonzalo de Sandoval, Blas Botello and Prince Xicotencatl are not entirely alien to us. If one looks at the chronicles, it would seem that the conquest was only a male affair. As Eloísa Gómez-Lucena ironically points out, Bernal included the names and characteristics of up to 16 horses in the expedition, but hardly mentions the women, both Castilian and allied, who took part.

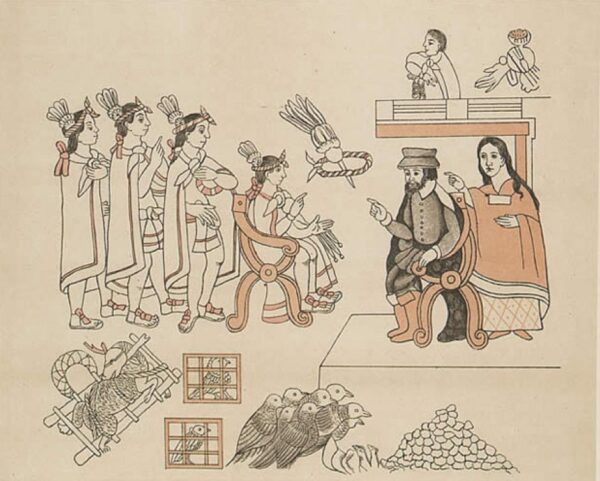

The great exception is Doña Marina, whom Bernal did highlight and about whom he admits that without her “we could not understand the language of New Spain and Mexico”. I will not dwell too much on Malinalli, renamed Doña Marina by the Spaniards and contemptuously nicknamed “Malinche” by the Mexicans. Her contribution to the conquest is fundamental and well known. I would like to point out, however, that the description of her as a traitor by some is not really fair. She was the one betrayed by her family, since she was sold by her stepfather as a slave. Moreover, Malinalli was not Tenochca, or even Mexica, but came from a village called Painala, and although she was ethnically Nahua like the latter and therefore spoke their language, in addition to the Mayan she learned in Potonchan, she did not feel in any way linked to the triple alliance. At the time, slaves owed allegiance only to their masters, but if he also freed her from slavery and made her his mistress, it is easy to understand why she became one of the main supporters of Cortés’ cause.

The role of women soldiers

The role of the Tlaxcalan women was also fundamental. A much lesser known role, but one that allowed the alliance with the people of the White Heron to be sustained, even in the moments of greatest weakness for the Spaniards, since all of Cortés’ captains married Tlaxcalan princesses. Some, like Alvarado’s wife Tecuelhuetzin, renamed Doña Luisa (María Luisa Xicontencatl), also played a very important role in the conquest.

Even more forgotten and unjust is the case of the Spanish women who took part in those military campaigns. Some, such as María de Estrada, left Cuba with Cortés, but most arrived in the expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez accompanying their husbands or partners, and after the latter’s defeat they flocked to the side of the Extremaduran.

And it is right that the Indians understand that we Spaniards are so brave that even their women know how to fight.

Maria de Estrada

The most notable of these women was the aforementioned María de Estrada, a Sevillian of Cantabrian origin who was married to Pedro Sánchez Farfán who, incidentally, was one of the soldiers who captured Narváez. María was very skilled with the buckler and sword and was also a great horsewoman. In fact, she saved many in the Noche Triste and fought at Otumba “with such fury and courage that exceeded the effort of any man” and “as if she were one of the bravest men in the world”, in the words of the chronicler Diego Muñoz Camargo. Before beginning the conquest of Tenochtitlan, Cortés, who had an extraordinary affection for her, tried to leave her in Tlaxcala to prevent her from running any more risks. Maria flatly refuses. “And it is right that the Indians should understand that we Spaniards are so brave that even their women know how to fight”.

Another woman who was particularly courageous was Beatriz Bermúdez de Velasco, better known as “la Bermuda”, who, according to Hugh Thomas, arrived in the late 1520s (although other sources place her in the Narváez expedition) and who, in one of the military skirmishes, aborted an escape by the Castilian soldiers by telling them that if they did not attack, she would do it herself.

Special mention should be made, among others, of Isabel Rodríguez, wife of Miguel Rodríguez de Guadalupe, who served as the troop’s doctor, and the Afro-Spanish mulatto Beatriz de Palacios, who was called “la parda” because of the colour of her skin and who was the wife of Pedro de Escobar (in 16th century Spain, by the way, marriages with people of different ethnicities were perfectly legal, which was not the case in other colonial powers). Beatriz fought with commendable courage and bravery on The Sad Night. Beatriz González, the Ordaz sisters and Elvira Hermosilla, wife of Juan Díez del Real and lover of Cortés, with whom she would have a son, were also brave soldiers and at the same time hard-working nurses.

Their unknown role, a reflection of the prevailing machismo of the time, is doubly unjust and should be vindicated, as they all fought alongside the men, some, as we have seen, with even greater courage, but at the end of the day, while the men were busy playing cards or drinking mead, they were busy looking after the wounded and carrying out a multitude of other tasks. Without the help of Marina, Estrada, Luisa and so many others, it is not certain that Cortés would have been able to conquer New Spain.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021