Source:El Debate

In 1839, the British chargé d’affaires in Madrid proposed the purchase of the island to the Spanish government. He cited the lack of attention and the usefulness of the British navy in suppressing the slave trade.

The islands of Fernando Poo and Annobón were ceded by Portugal to Spain in the Treaties of San Ildefonso in 1777 and El Pardo in 1778. That second year they were occupied by an expedition sent from Montevideo under the command of Brigadier Conde de Argelejo. With the expedition decimated and with no prospect of colonisation, they were abandoned in 1880, leaving them under nominal sovereignty and unoccupied.

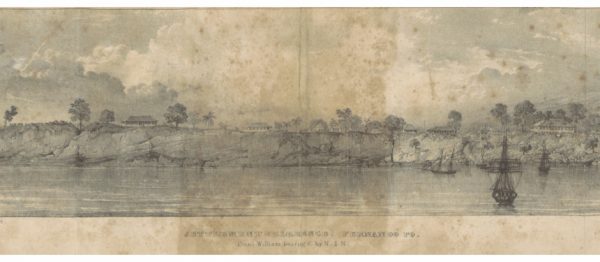

Around 1827, British ships visiting the island for supplies and water on their routes to the Cape and other colonies established a base in the northern bay, calling the small town Clarence, later Santa Isabel and now Malabo. Captain Owen, who was later appointed governor by London, was the viceroy there.

The small town had a certain prosperity; there were merchants, missionaries, factors, doctors, craftsmen and naval auxiliaries. So much so that it lived as if it were just another British colony, and it appeared as such on some English maps of the time. The reality was different: in 1823, taking advantage of the Earl of Ophelia’s trip to London, only the transfer of use was agreed. Some – from the later governmental position – argued that this act was the first attempt at purchase and that it was not concluded because the United Kingdom did not recognise Spanish sovereignty until 1835.

These actions highlighted Spain’s disengagement from territories it did not control, even if they were its own. There was too much territorial dominion and too little human and financial capital to exploit Guinea when it could not do the same with the Philippines, the Carolinas or the Marianas, which it had held for centuries.

Given England’s convenience and Spain’s disinterest, a purchase was proposed. Spain had been heavily in debt to the UK since 1828 and the interest on the debt was becoming too onerous. By 1839 the arrears were already four quarters in arrears. On 18 April of that year, the British chargé d’affaires in Madrid proposed the purchase of the island to the Spanish government. He cited Spain’s lack of attention to the possessions and the usefulness for the British navy in suppressing the slave trade.

At the time, the president of the Council of Ministers was Evaristo Pérez de Castro, who did not see the benefits of such a deal. In 1840, the Carlist War had ended, for the financing of which another debt was contracted with France and another large expenditure in interest payments, and the debt with Great Britain was increased by the expenses to be borne by the Auxiliary Legion sent by that country. After the momentary fall of Espartero, Antonio González, a second-rate liberal who was probably managed by the previous president, became president of the government. In 1841 he travelled to London, where he was received by Lord Palmerston, who advanced the project and offered sixty thousand pounds, which would pay off the interest but not the debt. On 9 July the Spanish government submitted a bill to the Cortes for the cession of the two islands for the indicated price. On the 26th of the same month, the Gaceta de Madrid published a long article justifying the decision on the grounds that the islands were unhealthy and had lost economic interest since the slave trade was banned. It concluded that keeping them would mean spending a lot of money. A commission was then formed to report on the project.

Then came an unexpected reaction: in the face of the possible sale, there was a huge national reaction that frightened the government. There were two causes: the meagre price and the offence to national dignity. And two fronts: the press and the parties.

The government project had defenders in publications such as Fray Gerundio or La Constitución, who believed that they were of no use to Spain, that they could not be considered part of the nation like Barcelona or Cadiz and that they were only useful for a few slave traders. In other words, the same arguments put forward by the president. However, the great defenders of Espartero and the government, El Eco del Comercio and El Hablador Patriota, hardly entered into the matter, presumably because they did not see the goodness of the matter. Against them were newspapers such as El Corresponsal de Aribau, which suspected that the sale of the Philippines, the Marianas and the Canary Islands might be behind this sale, and that it would close the door to future trade with the continent, given the strategic position of the islands. In the same vein, but with greater harshness, Andrés Borrego’s El Correo Nacional expressed, in long articles, that defending sovereignty was not a question of banditry but of nationality; and that the doors would be irremediably closed to future advantages for trade or agricultural colonisation.

The reaction of the press, which had never been interested in the islands of the Gulf of Guinea, was used by the moderate opposition to attack the government and the regent. It was also used to fuel the press campaign against those who wanted to diminish the Spanish territory for a pittance. The satirical newspaper El Cangrejo pointed out on 24 August 1841 that if the two little islands were worthless, why did the British want them? The press provided the opposition with arguments. The reaction to the project was very strong and the government did not feel it had the strength to maintain such an unpopular project. Finally, on 23 August 1841, Antonio González, Minister of State, informed the Senate of the regent’s decree withdrawing the project.

What became clear was that the government did not know what to do with the territories, but that, after the parliamentary failure, it had no choice but to devise something to gain control over them. And that was the origin of the 19th century expeditions to Guinea.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021