The undefeated Admiral who saved Europe from the Ottomans

Álvaro de Bazán y Guzmán, known sometimes as Álvaro de Bazán the younger, Marquis of Santa Cruz, was born in December 12th, 1526, in the city of Granada.

He was one of the most succesfull admiralls of all time, playing key roles in campaigns against the French Navy, English and North African pirates and most notably the Ottoman wars of the XVI century. His participation in the Battle of Lepanto, which prevented the Ottoman invasion of Italy and the expansion of the Ottoman Empire further into central Europe, have made him one of the more memorable naval commanders in history.

His was of noble ancestry, with various members of his lineage having distinguished themselves fighting under the kings of Navarre and Castille during the Reconquista. His father, Álvaro de Bazán y Manuel (Álvaro de Bazán the Elder) was a decorated naval commander and inventor who had made a name for himself in many military actions, including the conquest of Honaine in 1530 and the conquest of Tunis in 1535 against an alliance of Ottoman and French troops led by Hayreddin Barbarossa (“red beard”).

His family´s service to the Crown of Spain was rewarded from an early age: Carlos I (Carlos V of the Holy Roman Empire) presented him with the habit of the Order of Santiago when he was only two years old, and he was knighted in Guadix at the age of four. He acquired experience and seamanship by accompanying his father in various naval military campaigns, first in the Mediterranean and, after 1537, in the Bay of Biscay and Atlantic Coast.

The battle of Muros Bay

His first major contribution to naval warfare was his decisive action in the Battle of Muros of 1543 against an attacking army of the French, who had violated the terms of the Truce of Nice (1538) and had assembled a fleet to loot the northern coast of Spain including the towns of Lage, Finisterre and Corcubión.

The French army had set anchor in sight of the then-remote town of Muros, which they were holding at ransom demanding twelve thousand ducats. Alerted of their likely position by a previous attack of the French on some Spanish merchant ships, Álvaro the elder managed to catch them by surprise and launched an attack with his fleet that ended with the capture of twenty-three French vessels, the sinking of the French flagship and the death of three thousand French troops, for three hundred deaths and five hundred injured on the Spanish side.

Naval warfare in the XVI century still had a lot in common with the Mediterranean tactics used in antiquity, with galleys used as rams against enemy ships. Most of the combant happened between infantry units using firearms at arms length and swords. This battle was no exception, and both father and son participated in fierce fighting at close range.

The destruction of the French fleet eased the pressure on the northern coast of Spain, and eventually contributed to the signature of the Peace of Crépy between Spain and France.

His first command

Álvaro the younger received his first naval command when he was put in charge of protecting the merchant ships en-route to Spain from the Spanish Indies in 1554. He performed his military tasks in addition to managing his family´s naval business, concerned with the import of goods from the Americas. He took full control of this business on the death of his father in 1555. These merchant activities, however, tapered down over time as commerce with the Americas was increasingly monopolised by the Spanish Crown and as the importance and frequency of his military duties increased.

A Spanish galleass during the reign of Felipe II. Note the merged arms of Portugal and Spain flying at the stern, and the Papal arms on the mast.

As part of his activities in the Atlantic Ocean, Álvaro de Bazán made extensive use of his father´s inventions, most notably the “galleyed galleon”, a new design of galleon that Álvaro the elder had patented in Valladolid in 1550 and which gave the Spanish fleets a notable edge until it began to be used by the other navies of Europe. He had ample success in capturing corsair and privateer ships between the Iberian Peninsula, the Canary Islands and the Azores. He also participated in the efforts to supply by sea the Spanish troops in Flanders, and it was this involvement that allowed him to escape arrest in Seville in 1555 when a conflict with the local authorities put him in detention. A letter by Princess Juana, who was acting as Regent of Spain while prince Felipe -future Felipe II of Spain, who was de facto king while his father ailed in Yuste– was abroad, ensured he was freed. In fact, part of the reason for his freedom was that his fleet was required to travel to Flanders to pick up Prince Felipe.

He tried to use his influence with the Crown to promote the construction of Galleasses for permanent use by the Spanish Navy, so that the Navy could rely on its own ships instead of on impounded merchant ships for war or military operations, as was usual at the time. The impoundment system discouraged the ownership of vessels for merchant purposes, as it created a risk that many ship-owners could not insure. Thus, it was detrimental to the shipbuilding industry, as well as to the merchant industry. Both of these were lucrative to Álvaro de Bazán and his brother Alonso. Alvaro´s proposals were however rejected after lobbying by the Casa de la Contratación de Indias, which had a near monopoly on the trade with the Americas that was threatened by the proposals.

Return to the Mediterranean

These differences didn´t prevent the merchants in charge of the Casa de Contratación from requesting in 1562 Álvaro de Bazán´s help in stopping the Turk pirate Ayaya, who was causing them grave losses. In charge of eight galleys commissioned by the Casa de Contratación, de Bazán moved his activities to the Strait of Gibraltar, removing himself further from the running of the family business. Piracy in the Mediterranean and the Strait were a great concern to the Spanish Crown, which ruled over Sardinia, Milan, Naples and Sicily. Pirates had the support of the Ottoman Turks, and they had established bases on various locations on the northern coast of Africa. Thus, Álvaro de Bazán participated in attacks to destroy these bases, including the taking of the rock of Vélez de la Gomera (1564), which at the time was an island (nowadays it is connected to the African mainland by an isthmus); and the inutilisation of the port of Martil.

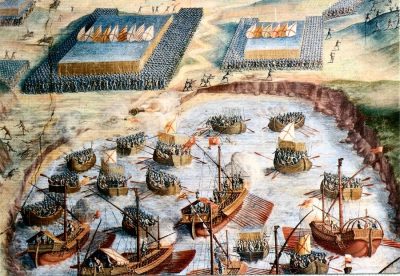

Martil (Río Martín in Spanish) was an important coastal town built next to the homonymous river in the coast or Morocco. The navigable river allowed pirates to defend themselves by sailing upstream almost to Tétouan, where they were protected by the Pasha. Taking Tétouan was not practical, so García Álvarez de Toledo, another illustrious sailor of the time, devised a plan to remove the pirates and proposed it to King Felipe II: close off the river by sinking ships filled with stones at its mouth. This would make navigation upstream impossible and therefore would eliminate the protection that pirate whips enjoyed from the heavily defended city of Tétouan. King Felipe II tasked Álvaro de Bazán with the mission, and after extensive epistolary exchanges between the two, a fleet was mobilised to proceed with the operation in February of 1565.

Secrecy was crucial to the success of the mission, and this was somehow compromised by an English pirate ship which gained broad knowledge of the plan to attack pirate bases and alerted several north-African Pashas that an imminent attack on one of their fortresses was imminent. It is worth noting that these pirates and privateers had a lot to loose from the destruction of pirate nests, even if these were held by Turks or Moors and not by Christians. The leak of information forced the fleet to return to Gibraltar, where it obtained further reinforcements. The attack went ahead with help from the governor of Ceuta, which at the time was ruled by the Portuguese. To cover the landing of the Spanish troops, the Portuguese launched a mock attack from the city of Ceuta that created a diversion to the north. While the Pasha travelled with his troops to confront the Portuguese, the Spanish disembarked with a small detachment of arquebusiers to secure the shores around the mouth of the river.

Álvaro himself proceeded to sound the mouth of the river from a small boat to find an ideal location for sinking the obstacles. Having closed off the river mouth by sinking boats loaded with limestone and rock, the troops on the ground were engaged by Moors who had finally realised the real intention of the Spanish. An infantry skirmish ensued, with the Spanish arquebusiers trying to cover the retreat to the boats. Fortunately for the Spanish, the close-quarters action was too much for the Tetouanese, who retreated and allowed the safe boarding of the remaining Spanish troops. The success of the operation, which not only disabled the pirate base but also trapped fourteen pirate ships (these were later released by dismantling them and re-assembling them outside the barrier) endeared Álvaro to the King and to García Álvarez de Toledo, who would be his commander in the subsequent campaign against the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman wars and Lepanto

The Ottoman attack on Malta in May of 1565 was a decisive feat in Álvaro´s life. Surrounded by a superior Ottoman fleet, the island of Malta was close to falling in Turkish hands. This would have been an economic and military disaster for the European powers of the time. The Spanish fleet was required to provide infantry reinforcements to the island to support the defending troops. As the island was surrounded by Ottoman ships, this implied a great risk. Direct confrontation with the overwhelming Ottoman fleet out of the question, de Bazán proposed using a small group of fast galleys to cross the enemy lines undetected and at speed, avoiding combat. His plan worked and allowed nine thousand men to disembark on the island, providing relief to the besieged Christian troops. This proved instrumental in repelling the Ottoman attack.

His multiple naval successes were rewarded in 1569 when the King created him Marques of Santa Cruz.

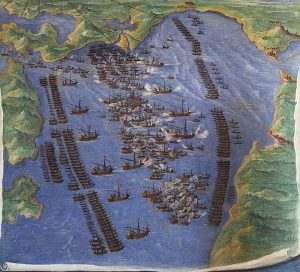

His greatest single success, however, came in the battle of Lepanto. While many modern Europeans see Europe as the ruling civilization throughout most of modern history, people in Western Europe had just witnessed the fall of the Byzantine Empire at the hands of the Turks, and an increasing threat from the Muslim world that threatened with domination in the Mediterranean. Indeed, the Ottomans had control of the Balkans and had sieged the city of Vienna in 1526. In this context, and given the increasing territorial gains by the Ottomans that threatened the Italian Christian states and the Papacy, a Holy League was formed in 1571 between Spain, Venice and the order of St. John to create a unified navy that could stop the Muslim advance into Christian territory. The Holy League confrontred the Ottoman navy in the Gulf of Patras, and the Battle of Lepanto ensued.

The Spanish and allied victory at Lepanto was celebrated in the whole of the Christian world. Miguel de Cervantes, who famously lost his hand in the battle, would call it “the highest occasion that the centuries have seen”. It was the first major naval defeat of the Ottomans since the fifteenth century, and put an end to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. While the effects of the Christian victory were not immediately obvious in terms of territorial gains, the battle prevented the Ottoman conquest of Italy and a severe blow to the Venetian trade capability.

Alvaro de Bazán’s career however did not end with the victory at Leptanto. He continued to participate in naval warfare against the Ottomans as part of the Holy League until this was disbanded, and then participated in the re-conquest of Tunis in 1573. This was successful although only for a short time, as Tunis was retaken by the Ottomans the year after.

Portuguese succession crisis, the Azores campaign

Further military campaigns in the Mediterranean against the Ottomans and against piracy continued until in 1580 Phillip II, King of Spain, required him to participate in the campaign of Portugal against the allies of Antonio, Prior of Crato, who had proclaimed himself king of Portugal in detriment of Philip. After the swift defeat of Antonio´s military in mainland Portugal, he retreated to the Azores, were he reigned and planned an eventual retake of the whole kingdom. Failed attempts to take the islands by Alonso de Bazán (Álvaro´s brother) and Pedro de Valdés prompted King Phillip to task Álvaro with the mission in 1582. Antonio had enlisted the help of the French, always keen to reduce the influence of the Spanish Crown, and a naval battle between the French and Spanish navies ensued on July 26th, 1582, resulting in the destruction of the French fleet (ten ships sunk, no Spanish ships lost) and the death of the French commander, Felipe Strozzi. Since no official war had been declared with France, all the captured prisoners were regarded as pirates and executed, following the laws of the sea.

The Azores, however, remained under the control of Antonio. Álvaro de Bazán was forced to escort a fleet returning from the Americas, and therefore the landing on the islands was postponed until the following year. The opportunity to obtain reinforcements was not enough for Antonio, however, and his troops, as well as the French allies who were helping his cause were swiftly defeated in July of 1583. For this, he was created Grandee of Spain by the King, and Captain General of the Ocean and of the men-of-war of Portugal.

Preparations for the Armada, death and legacy

He persuaded King Phillip to organise the Spanish Armada against queen Mary of England. He began to organise the invasion of England, but had to interrupt this because of the need to intervene in the defense of the returning American fleet. A typhus epidemic further delayed the departure of the Armada, and eventually ended Álvaro de Bazán´s life. The King had become impatient with delay in the preparations, and Álvaro received shortly before his death the news that he had been removed from command of the Armada, and that his role would be taken by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, who had no naval experience.

Álvaro de Bazán y Guzmán was one of the most successful naval commanders of all times, whos victories shaped the future of Europe and who pioneered new technologies and naval strategies that would define naval warfare in the following century. His warfare successes are only comparable with his vision of a professional navy formed of purpose-built warships, which would not become the norm until many years had passed from his death.

The modern Spanish Navy always names an illustrious ship after him, as is also the case with Blas de Lezo and Cristóbal Colón.

Sources

- Real Academia de la Historia, ‘Álvaro de Bazán y Guzmán’, 2018. Available at:https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/8233/alvaro-de-bazan-y-guzman. (Accessed 14 October 2021).

- Real Academia de la Historia, ‘Álvaro de Bazán y Manuel’, 2018. Available at: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/115412/alvaro-bazan-y-manuel. (Accessed 16 October 2021).

- Instituto de Historia y Cultura naval, ‘Batalla de Muros’, de Armada Española 1542-1555, pp. 269-279. Available at https://armada.defensa.gob.es/html/historiaarmada/tomo1/tomo_01_20.pdf. (Accessed 16 October 2021)

- Todoavante.es, ‘Río Martín Cegado 9/III/1565’. Available: https://todoavante.es/index.php?title=R%C3%ADo_Mart%C3%ADn_cegado_9/III_1565. (Accessed 16 October 2021).

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021