Source:Libertad Digital

Libertad Digital publishes, for the first time in Spanish, the report of the International Red Cross delegate on the attack by two Republican fighters on the plane in which he was travelling. He had denounced to Geneva the massacres of prisoners in Madrid.

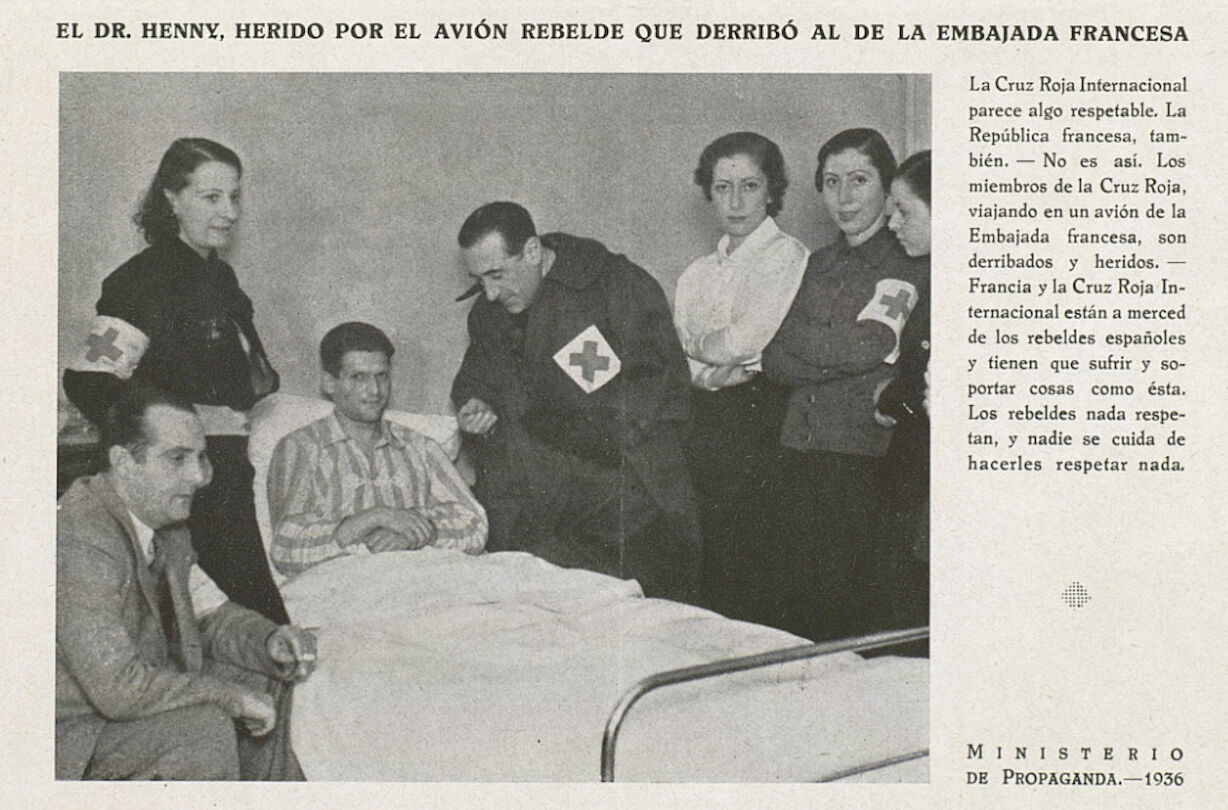

On 8 December 1936, over the town of Pastrana in the Alcarria, a Potez-54 aircraft belonging to the French Embassy in Madrid was strafed by a Republican fighter. The attack caused the plane to crash-land and resulted in gunshot wounds to three of the five passengers. Among the wounded was Georges Henny, a Swiss doctor, delegate in Madrid of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), who had denounced the removal of prisoners from Madrid prisons and their mass murder in Paracuellos de Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz. Libertad Digital publishes today, for the first time in Spanish, the report that Henny himself wrote about the attack that wanted to end his life.

Between Republican repression and Franco’s bombings

At an altitude of over three thousand metres, on board the French Embassy’s Potez-54 mail plane that was taking him from Madrid to Toulouse, the lands of burning Spain must have seemed to the young Dr Georges Henny like a peaceful landscape. He left behind a capital ravaged by Republican repression and Franco’s bombing raids.

The battle continues at the gates of Madrid, we fall asleep to the sound of machine guns and wake up to the sound of cannon or bombs destroying our headquarters. (…) However, this climate of war does not affect me as much as the thousands of people who come to cry at our headquarters and the outrages I hear about every day – he had written to his superiors only six days earlier.

Tension and exhaustion, coupled with dark emotions at the horrors of war, especially that of the thousands of prisoners murdered on the outskirts of Madrid, one of whose freshly covered graves he had seen with his own eyes near Torrejón de Ardoz, had taken their toll on the Red Cross delegate.

I am getting more and more fed up, and if I didn’t feel I was being a little useful here (much less than I would have liked), I would have already announced to you my return to Geneva, which I hope will hardly be delayed – he admitted on 2 December at ICRC headquarters.

The days leading up to the trip

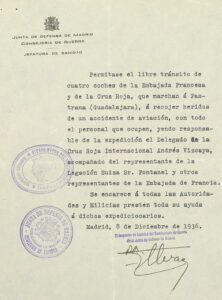

The excuse – planned? untimely? – for leaving Madrid was to accompany two Spanish girls, María Carlota and María Dolores Cabello y Sánchez-Pleités, daughters of Pedro Cabello Maíz, an architect, and María Carlota Sánchez-Pleités y Jiménez, Marquise de Los Soidos, on their departure from Madrid.

Henny had been arranging their repatriation by plane since at least 24 November, according to one of her communications to Geneva. We know that the girls were scheduled to leave on 28 November, but the trip was finally cancelled. At no time did Henny declare her willingness to travel with them. There is, in fact, no prior communication from Henny to the ICRC about her trip from Madrid to Toulouse.

The plane was scheduled to leave on 6 December with Henny and the girls, who were included in the ticket thanks to the efforts of Emmanuele Neuville, the French Consul in Madrid. Also on board were French journalists Louis Delaprée of Paris-Soir and André Château of the Havas agency. The crew consisted of pilot Charles Boyer and radio operator Bougrat.

An engine failure forced them to postpone their departure until the 8th.

The surprise attack

After take-off, and only a few minutes into the flight, the Potez-54 was flanked successively by two Republican fighters, perfectly identified by the pilot of the civilian plane, Boyer, who saluted them with a slight movement of his wings.

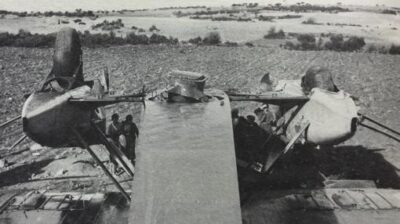

Machine-gunned civilian plane in which Henny was travelling | From the book “Morir en Madrid”, Raíces.

Instantly, the second fighter came under the Potez-54 and strafed it, injuring Henny, Delaprée and Château. Boyer played dead and dropped the aircraft to the ground, pretending to go into a tailspin so that the fighter would not continue firing at them. With great coolness, Boyer managed to crash-land on farmland seven kilometres from Pastrana, where the plane was topped off.

Given the shocking vividness of Georges Henny’s account, which we are publishing today for the first time in Spanish, more than eighty-six years later, there is no need for commentary. But I cannot resist highlighting the scene of the Red Cross delegate, a doctor by profession, coming to the aid of the wounded on one leg, as he too has a bullet embedded in his right calf. After being treated in Pastrana, the wounded were transferred to different hospitals.

Delaprée, aged 34, died three days later in the Hospital de San Luis de los Franceses, at calle Claudio Coello Street 32, in Madrid. It so happens that he had denounced in his chronicles from Madrid the massacres of civilians as a result of the bombardment by Franco’s artillery and air force. His chronicles were published in 2013 under the title Morir en Madrid, published by Raíces, edited by the Hispanist Martin Minchom.

Machine-gunned civilian plane in which Henny was travelling | From the book “Morir en Madrid”, Raíces.

For his part, Château, hospitalised in Guadalajara with a shell wound that fractured his tibia and fibula, suffered the amputation of his right leg. One of the two Spanish girls, Maria Dolores, treated at the French hospital in Madrid, suffered a fractured forearm, and her sister suffered injuries to her face and legs.

Henny was taken to the Palace Hotel hospital in Madrid, where the bullet was removed. The bullet was kept in a safe in the archives of the ICRC in Geneva and later deposited in the Red Cross Museum. Historian Sébastien Farré had it examined a couple of years ago: it corresponded to the ammunition used by the machine guns of the Soviet Polikarpov fighters of the Republican air force.

The confidential report

Henny’s own report on the shoot-down was written a month after the attack, after his repatriation to Geneva on 17 December. It is important to note that he wrote the confidential report after the note of protest that the French government sent on 29 December to Largo Caballero’s government, confirming that a Republican fighter had shot down the aircraft, which Madrid had repeatedly denied, accusing German planes on Franco’s orders.

The French government confirmed that the Potez-54 was the same aircraft that had been flying the Madrid-Toulouse route without incident until then, which refuted the claim that it had not been sufficiently identified, even though it was a bomber converted for civilian flights. According to the protest note, the attack was carried out by two fighters with the distinctive red stripes of the Republican air force.

In his memoirs, the then head of Republican fighter aviation, Andrés García Lacalle, identified Gheorghij Zajarov and Nicolai Shmelkov as the Russian pilots who took part in the shoot-down, although the former justified the attack by saying that the French plane was shooting at him with its machine guns, which was completely impossible as he was unarmed, as they could see when they flew alongside him to identify him and salute the pilot.

Marcelin, a Frenchman in the service of the War Ministry

Dr. Henny leaves no room for doubt about this authorship, especially given the testimony of the pilot Boyer and the radio operator Bougrat. But he adds even more intrigue by referring to the research carried out for the French government by Emmanuele Neuville, consul in Madrid, who identifies the presence, first in Barajas at take-off and then in Pastrana once the shoot-down was known, of a French subject by the name of Marcelin, whom he places in the service of the Republican War Ministry, whose head was Largo Caballero himself. “There is one who won’t make it anyway”, Marcelin said when he finally saw the plane take off at Barajas, according to what Neuville told Henny.

The Frenchman’s name is deleted from the copy of Henny’s report that Jacques Cheneviere, a member of the CIRC, sent on 16 January 1937 to René Massigli, a senior representative of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Henny’s first report has been preserved without item 1 and part of item 2, which is contained in the copy sent to Massigli. I have therefore considered it useful to cross-reference the two copies to obtain the complete version.

What did the Republican government fear?

In Cheneviere’s letter, the Red Cross is grateful that Paris has demanded compensation for Henny and Maria Dolores Cabello from the Spanish government, but informs that the organisation will not be making any claim. This precaution, like all the Red Cross precautions surrounding the shooting down of the French plane, was intended to avoid compromising the safety of the rest of its delegates in the Republican zone.

The ICRC’s Civil War collection being made available by the Spanish Red Cross Documentary Centre raises questions about the version that has been circulating since then, according to which Henny travelled to Geneva with documentary and graphic evidence of the massacres of prisoners in Madrid to coincide with the extraordinary meeting in the Swiss city of the Council of the League of Nations requested by the Spanish government to denounce the military intervention of Germany and Italy.

This version is already recorded in 1938 by Schlayer in his book on popular-front Madrid, from which he was finally expelled in July 1937 after an episode in the port of Valencia, about to embark, which made him fear for his life.

The testimony of Francisco Cortijo Ayuso, a doctor from Pastrana who treated the wounded at the scene of the accident, which was published in the Revista Española de Historia Militar in March 2001 by Felipe Ezquerro and I quote in my book Eso no estaba en mi libro de la Guerra Civil, contributed to the credibility of this account. Dr Cortijo stated that he saw the passengers on the plane burn a leather briefcase and photographs in a bonfire. He also stated that, before the arrival of several cars with authorities from Madrid, Dr. Henny entrusted him with two bags from the diplomatic pouch which he was able to hand over to the secretary of the French Embassy. None of these details appear in Henny’s report.

The injured girl, María Carlota Cabello, would testify in 1941 in Franco’s Causa General, at the age of 20, that Dr. Henny put the pouch under the legs of her sister María Dolores, and that she believed that the delegate was later able to take the pouch out of Spain. He also said that, according to what he was told in Paris, “without being able to specify who or whom”, the suitcase contained a report and a documentary entitled “Spain in flames” about the “red” crimes.

The same file contains a statement by Andrés de Vizcaya, deputy delegate of the ICRC, who went to Pastrana with an ambulance. There he saw the aforementioned Marcelin, whom he identifies as a French agent in the service of the Defence Junta presided over by General Miaja.

With regard to the accusatory material that Henny may have carried with him, Vizcaya claims that at Barajas there were censorship controls by elements of the FAI, despite the fact that Henny says in his report that his luggage was not checked at customs because he was carrying a diplomatic passport. Vizcaya claims, however, that

Dr. Henny could not have carried anything in his luggage that could compromise him, all the more so because the diplomatic pouch of the Swiss Embassy sent to Geneva abundant and specific information on the murders and acts of barbarism committed in the red zone, especially in Madrid, having been sent shortly before the departure of the plane detailed information on the murders and events that took place in the Madrid prison (sic).

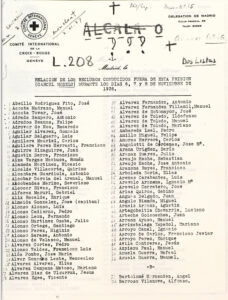

The CIRC delegate had sent two reports, on 24 November and 2 December, on the massacres of prisoners, together with lists of detainees transferred and those executed. Here I agree with Sébastien Farré that, as Vizcaya stated, the ICRC was already fully informed by Henny of what happened in Madrid. As Vizcaya points out, the ICRC delegation did not keep any more information apart from what had already been sent, for fear of a search that could have fatal consequences.

Several protagonists in this story, from the journalist Château to the French consul Neuville, claimed that Henny was the target of the attack. According to the British journalist Sefton Delmer, a correspondent during the Spanish war, the order to shoot down the plane was allegedly given by Alexander Orlov, the head of Russian espionage in Madrid, who was also involved in the kidnapping and assassination of Andreu Nin, leader of the POUM, on Stalin’s orders.

Perhaps the question is no longer whether the shooting down of the Potez-54 was an accident or a mistake, but whether it was a pre-emptive strike, on the suspicion that Henny was carrying new evidence that might damage the Madrid government, or a revenge attack to make him pay for the damage already caused by his denunciations of the international image of the Spanish Popular Front.

The assault on the Finnish embassy

Henny’s unexpected departure from Republican Spain, with the excuse of accompanying two girls on their repatriation, after asking the French consul to allow him to travel as an exceptional favour, which he granted “after some hesitation”, points to a powerful motivation beyond the young doctor’s need for rest after ten weeks in hell.

The reason for this can be found in his telegram to Geneva on the 5th, the day before the first unsuccessful departure of the French plane. At 8.45 p.m., at the CIRC headquarters, Henny “urgently” reported the raid by government forces on the Finnish Embassy, denouncing this violation of the legation’s extraterritoriality as “an affront to the dignity of the diplomatic corps in Madrid”. Its cable contains an alarming appeal: “Violation of several other legations seems very likely, several thousand Spanish lives seriously threatened“. To this end, he called for urgent intervention with the League of Nations “to examine asylum-seekers’ questions and guarantee their safety as quickly as possible”.

This was Henny’s last communication before leaving Madrid. The Red Cross delegate would undoubtedly not have left the city in such dire circumstances if he did not fear a direct threat to his life. That is why he was able to arrange with the French consul Neuville as a matter of urgency to be included on the next day’s plane ticket, claiming that he was leaving with the Cabello girls. Perhaps he thought that if he travelled on a plane under the French flag, his persecutors would be afraid, and even more so if there were other passengers, including two girls.

I would even go so far as to suggest the hypothesis that his hasty departure from Spain, without prior warning to Geneva, was advised by a Republican leader: I am thinking, for example, of the anarchist Melchor Rodriguez, who took up his new post as special delegate for prisons in Madrid on that very day, the 5th.

I do not want to leave aside Sébastien Farré’s recent observations on the downing of the plane. After ruling out that Henny was the target of an in-flight attack because of his revelations about the massacres of government prisoners, Farré assumes that he could have been the target of the attack, but not because he was carrying evidence of Paracuellos, but because he could have been a German or Francoist spy, or because the French plane was carrying information on the defences of Madrid for the rebel side.

Schlayer’s secretary in the Norwegian legation, Manuel Jiménez-Alfaro y Alaminos, referred to this dispatch in a 1944 letter. We have already demonstrated the caution with which the alleged espionage services of Jiménez-Alfaro noted in 1944 had to be taken when, in his prosecution by the victors in 1939 for having remained in the “red” zone, he did not mention them.

Farré at least acknowledges that he has no evidence to support such claims. There is, on the other hand, to rule out that Henny was a Nazi or Francoist spy, an accusation that the Red Cross delegate himself bore at the time with stoicism, as when he noted that “it is difficult to admit here that one can be interested in the prisoners without being a fascist or a spy”.

Henny’s alleged collaboration with the rebel side is also easy to disprove. Suffice it to mention his firm refusal to send Franco the lists of prisoners obtained in the Madrid prisons, as Schlayer intended. Henny considered it “impracticable” to do so because “the CIRC cannot transmit to one of the parties information obtained in some way illegally and to the detriment of the other party”, thereby demonstrating a deep and profound sense of the neutrality of his humanitarian mission.

As Farré points out, Henny is the great forgotten figure in the history of the ICRC in our conflict. He is also forgotten in the history of the Civil War, as one of those heroes who, at the risk of their lives, tried to alleviate the suffering of Spaniards on both sides.

Henny, who left Spain for good on 17 December 1936, died in 1991 after having practised medicine in the Geneva town of Grand-Lacy, after a discreet life, single and without descendants. His name deserves to appear with full honours in the pavilion of the great good men who helped Spain in the worst of its hells, although I would be content for him to have an entry in the biographical dictionary of the Royal Academy of History.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1572 Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva founded the town of Guaduas (Colombia).

- 1578 Brunei becomes a vassal state of Spain.

- 1672 Spanish comic actor Cosme Pérez ("Juan Rana") dies.

- 1693 Painter Claudio Coello dies.

- 1702 The Marquis de la Ensenada was born.

- 1741 Spanish troops break the siege of castle San Felipe in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia).

- 1844 The Royal Order of Access to Historical Archives was promulgated.

- 1898 President Mckinley signed the Joint Resolution, an ultimatum to Spain, which would lead to the Spanish–American War.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021