Source:Libertad Digital

“There was a pit filled with fresh earth. You can imagine what it concealed”. New data and testimonies of the so-called “black expeditions”. Doctor Henny visits the places “of the most dramatic tragedy”.

Dr. Georges Henny, delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Madrid, arrived on 7 November 1936 at the Modelo prison in the hours before several expeditions of prisoners were led to Paracuellos del Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz to be mass murdered. Libertad Digital publishes for the first time in Spanish the full report that Georges Henny sent to the Red Cross in Geneva on these massacres.

The papers from the Documentation Centre of the Spanish Red Cross belonging to the Civil War collection of the ICRC archive reflect Henny’s tireless activity to alleviate the suffering of the victims of the conflict, but also the desolation that the terrible events of the conflict produced in his mind.

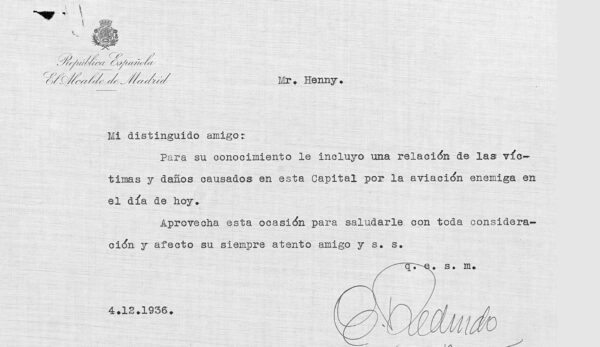

From 23 October, the day of Franco’s first major air raid, which inaugurated the first systematic bombing of a major city in history, Henny was informed daily by the Madrid City Council about the victims of Franco’s bombs, which in November alone caused 305 deaths and 1,197 wounded.

Henny’s concern was also growing about the daily murders, the result of the activity of the three hundred checkas belonging to political parties and unions aligned to the Popular Front and operating in Madrid, and especially about the situation of the prisoners in Madrid’s prisons in view of the imminent assault on the city by the rebels.

The Red Cross delegate’s concern was aggravated by the refusal of the head of the government, the Socialist Francisco Largo Caballero, to send him the lists of prisoners he had repeatedly requested since his arrival in Spain. He was also dismayed by the insistence of the Popular Front government that the detainees under its responsibility could not be protected as prisoners of war in accordance with international conventions, since they were “political prisoners”.

The visit to the Modelo prison

On the same day that Franco’s attack on Madrid began, Saturday, 7 November, Dr. Henny went to the Modelo Prison, near the Plaza de Moncloa, with the Norwegian Consul Felix Schlayer. The departure of the government for Valencia the previous evening had increased the diplomatic corps’ concern for the fate of the prisoners.

Hundreds of Madrid residents at the Red Cross headquarters trying to find out where their missing relatives are | CDCRE, ICRC Archives

On arriving at the Modelo, they found that access to the prison was cut off by barricades and that there were numerous double-decker municipal buses outside the gate. The deputy director of the prison confirmed that the prisoners were being transferred. Young Henny and old Schlayer decided to meet General Miaja, appointed head of the new Madrid Defence Board, and his adviser for Public Order, Santiago Carrillo, to ask for guarantees for the prisoners’ lives. “The prisoners would not be touched a hair”, Miaja told them, Schlayer recounts in his book Diplomático en el Madrid rojo.

On 10 November, the day after the appointment of Melchor Rodriguez, the “Red Angel”, as Inspector General of Prisons, Henny and Schlayer visited the anarchist leader and noted his willingness to guarantee the lives of the prisoners. They did not hesitate to recognise him for his commitment and that of his collaborators to accompany future expeditions between prisons to their destination, and to be “ready to sacrifice their lives in defence of the prisoners”.

Henny will visit the prisons on the 11th and 12th to check that the “black expeditions”, as those that ended up in mass graves were called at the time, are effective. He is doing so despite the fact that warnings about the risk posed by these visits have never made more sense. On the 12th, in fact, the ICRC delegation’s security was reinforced when the militia guards were replaced by assault guards.

Schlayer and Henny’s investigations into the fate of the detainees taken from the Modelo led them to the atrocious discovery, on 13 November, of the place where several hundred of them had been murdered near Torrejón de Ardoz. All of this is recorded in the report that Henny sends on 24 November to the Red Cross headquarters in Geneva through the diplomatic pouch of the Swiss Embassy.

To his report, which we [Libertad Digital] are publishing today for the first time in its entirety, Henny enclosed the report written in Spanish by Schlayer, dated 17 November, for the Norwegian authorities and the diplomatic corps. In his note, Schlayer refers to his own discovery, on 15 November, of the recently covered graves in Paracuellos del Jarama.

I myself saw the day before yesterday – writes Schlayer – mounds of freshly raised earth, stretching from the road to the river in several rows, covering the corpses of at least 700 prisoners who were shot to death right there where there were apparently already ditches opened on purpose.

Schlayer’s report also contains his first testimony on the order to hand over the prisoners of the Modelo, signed by the deputy director general of Security, Vicente Girauta. “I have seen it. However, the order was given by Director General Manuel Muñoz on the night of the 6th to the 7th, before his flight to Valencia”, says the Norwegian Consul.

The testimonies of Henny and Schlayer have the historical value of being the first official notifications of that barbarity, along with the report that Pérez Quesada wrote for his Argentine superiors also on 17 November.

The visit of Henny, Schlayer and Pérez Quesada to the site of the massacre in Torrejón de Ardoz, the date of which has always been doubtful, can be dated with certainty to 13 November. This can be deduced from a communication from his deputy Andrés de Vizcaya, who reports that Henny is visiting prisons with Schlayer on that day.

In fact, they had gone to Alcalá de Henares to check which prisoner expeditions had arrived in the city of Cervantes. Later they went to Torrejón, where, on the basis of confidences, they located in Soto de la Aldovea the site of the mass execution of about 400 prisoners from the Porlier and Modelo prisions.

“In an area of about 200 m there was a pit 2.5 m to 3 m deep filled with fresh earth. You can imagine what this earth concealed”, Henny wrote to Geneva.

On the same day, Henny and Schlayer visited Jesús Galíndez, PNV delegate in Madrid, to whom they recounted their discovery of the massacres – “with a voice cracking with emotion”, their host wrote. This information reached Minister Manuel Irujo, who asked General Miaja and the Minister of the Interior, Ángel Galarza, about the prisoners. Both assured that they were all safe and sound.

The lie about the transfer of prisoners

After his atrocious discovery in Torrejón, Henny is dedicated to confirming with the prisons of Chinchilla (Albacete), Valencia, Alicante or Figueras (Gerona), supposed destinations of the prisoners, whether any of the expeditions have arrived there. None of them have received a single detainee from Madrid, according to Henny, who will never cease to recognise the humanity of the prison officers who collaborate in his investigations.

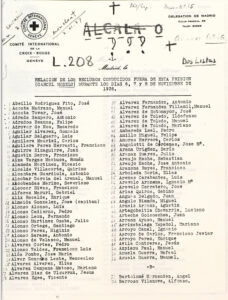

On the 16th, when the Modelo was to be evacuated due to the proximity of Franco’s forces, who were already in the Ciudad Universitaria, Henny entered the prison to supervise the prisoners’ departure. At the same time, he managed to get hold of the lists of the prisoners who, according to his information, had been transferred on the 6th, 7th and 8th. To do so, he was accompanied by Vizcaya and two typists to copy the lists while Franco’s bombs were falling, killing and wounding some prisoners. This circumstance did not deter him, as he returned that same afternoon to continue, under fire from the attackers, the compilation of the names of prisoners who had been transferred.

These lists will accompany the report sent by Henny to Geneva on the 24th, which will include those of the Modelo prisoners transferred on the 16th to other prisons in Madrid, but also others with the detainees, a total of 970, who never reached their destinations in the sacas of 7 and 8 November.

On the 18th, when, after Melchor Rodriguez’s resignation on the 14th, the sacas and killings of prisoners had begun again, Henny and Schlayer went to the women’s prison in the Conde Toreno convent because of a call from the director, who told them that the 1,400 women prisoners refused to be evacuated from the war zone for fear of being killed. Finally, thanks to the assurances offered by Henny and Schlayer, they agreed to leave and were safely rehoused in the San Rafael asylum in Chamartín. A fortnight earlier, according to Schlayer’s memoirs, he and Henny had prevented the sacking and murder of the women.

The Popular Front massacres, an international scandal

The massacres continued until 4 December, the day before Melchor Rodriguez was re-appointed head of Madrid prisons, now as special delegate. His appointment will mean their definitive halt due to the impossibility of continuing to hide them in the face of the international scandal promoted by denunciations such as those of Henny and Schlayer.

During this time, Henny also worked to persuade the Republican authorities to accept the ICRC’s proposal to create a neutral zone, reserved for the non-combatant population, from Paseo de Ronda (today Raimundo Fernández Villaverde) to Génova and Goya, and from Zurbano to Velázquez. Largo Caballero opposed it head-on, although it was viewed favourably by General Miaja.

For the Republican authorities, it would legitimise the rebels’ bombing of the rest of Madrid, as well as being similar to the appeal made by Franco’s propaganda for the civilian population to concentrate in the Salamanca neighbourhood. “I regret the government’s refusal to create a neutral zone, which, despite the difficulty of its realisation, would be very necessary,” Henny wrote to Geneva.

“The situation in Madrid is becoming sadder and sadder,” he wrote in the report, in which he expressed his despair at the effects of the bombing, which even reached the Red Cross hospital on what is now Avenida Reina Victoria. “We also see convoys of people wandering through the rain, carrying their furniture in whatever way they can, or whatever they have deemed most necessary to carry,” he writes.

The setbacks and difficulties of his mission also weigh on his mind. “The work in these conditions is very unpleasant, you get very little satisfaction, less and less, from people who are furious about the bombardments,” he admits.

At the same time, he felt powerless in the face of the ICRC’s inability to stop the attacks by Franco’s air force. Thus, on 18 November, the day after the bombing of Madrid with incendiary bombs, he asked in a telephone call to Geneva: “The ICRC delegation receives numerous complaints on this subject. Does the ICRC believe that it is possible to take measures to put an end to this bombing?”

He was also disheartened that his work was suspected of being sympathetic to the opposing side, if not outright espionage. “It is difficult to admit here that one can be interested in the prisoners without being a fascist or a spy,” Henny assures us.

In his own headquarters, Henny knows that he can be watched by the staff. “I have at my disposal a large number of volunteer staff controlled by the Popular Front Government,” he writes. He also reveals that a former representative of the Spanish Red Cross, Dr. Jacinto Segovia, had declared that “the whole International Committee [of the Red Cross] is composed of extreme right-wing people and generals.” “It is useless to give too much importance to these facts, but I wanted you to know,” he added to his colleagues in Geneva.

The report that shocked the International Red Cross

On 2 December, Henny sent Geneva a new report with new lists of prisoners taken out of the prisons. These were expeditions carried out between 16 and 30 November to Alcalá de Henares. Those of the 27th and 30th, as he reports, are of prisoners “allegedly released”, although he later notes: “Probably executed”.

The data that Henny reveals in this report must have chilled the ICRC. Referring to the evacuation of prisoners and the lack of transport for this purpose, he states that “many are let free”.

However, there are two kinds of freedom, an effective and real freedom and another freedom which frees those who are the object of it definitively and forever from all worries. In fact, all the prisoners who are executed (it is fairer to say murdered) are declared as released in the lists I have obtained and announced as such in official statements – he says.

His information about what happened is becoming more and more accurate, and he has no qualms about bringing it to the attention of his ICRC superiors:

I know that recently – Henny writes -some 470 prisoners have been shot near the Barajas airfield, where a grave was already planned. According to what I have been told, the prisoners were taken by bus to this grave prepared in advance, brought down with their hands tied in groups of ten and shot in front of those who were later to suffer the same fate. These 470 prisoners came from San Antón and must be the ones who appear on the lists as having been released. I have no further information about what happened in other prisons, but I know that in one of them (General Porlier) many other deplorable events took place.

Often, prisoners released in the morning are re-arrested the same afternoon and sometimes killed – says Henny, who points out that those released only wish to take refuge in an embassy with their families -. The embassies are full and can no longer accept any more people. However, they cannot put people on the streets who are in mortal danger – he stresses.

Speaking of the worsening conditions for prisoners due to lack of food, cold and overcrowding, Henny quotes a prison director who confesses his despair at not being able to do anything to improve the situation. Among the detainees were three boys aged between 14 and 15 and a 60-year-old man who had been Azaña’s teacher. “He, who treated the rogues entrusted to him with the greatest kindness and like a gentleman, is forced to behave like a rogue with people who are gentlemen (his own words),” writes the Red Cross delegate.

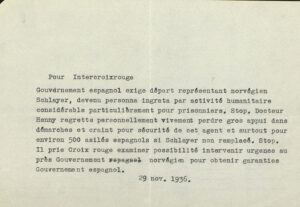

The report of 2 December also denounced the Largo Caballero government’s intention to expel Felix Schlayer, who had been declared persona non grata, from Spain. Henny blames the decision on the Minister of State, Alvarez del Vayo, “who does not like us to examine very closely what is going on in the prisons and around Madrid”. He prevented his friend’s expulsion by mobilising the ICRC and the Norwegian government. To do so, he appealed to the support he had given him in his efforts, the fate of the refugees in the Norwegian legation and, above all, “fear for Schlayer’s safety”.

Barely two months after his arrival in the capital, the young Swiss doctor knew very well what the final price of his humanitarian mission in burning Spain would be. He was already absolutely certain that life in war-torn Madrid was worthless. Even his own.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021