Source:Libertad Digital

Libertad Digital offers Spanish readers for the first time the publication of the documents of the Swiss doctor Georges Henny, delegate in Madrid of the ICRC.

The head of the Republican government, the Socialist Francisco Largo Caballero, refused to provide the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with a list of the detainees in Madrid prisons three days before the massacres of these prisoners began in Paracuellos del Jarama. Libertad Digital offers for the first time to Spanish readers the publication of the documents of the Swiss doctor Georges Henny, ICRC delegate in Madrid.

The meritorious efforts of the Documentation Centre of the Spanish Red Cross to catalogue and digitise the archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Geneva on the Civil War are providing new documents of extraordinary interest on our conflict. Among them are those related to the massacres in Madrid of thousands of prisoners considered to be disaffected with the Popular Front cause between October and December 1936.

This documentation records the activities of the young Swiss doctor Georges Henny, ICRC delegate in Madrid between September and December 1936. Henny was, together with the Norwegian Consul Félix Schlayer, 63, and the Argentinian Chargé d’Affaires Edgardo Pérez Quesada, 54, one of the key witnesses to the rounding up of prisoners from Madrid prisons, who were driven by the thousands to mass murder in the Madrid towns of Aravaca, Rivas-Vaciamadrid, Paracuellos del Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz.

Dr. Henny’s humanitarian work

The reconstruction of Dr. Henny’s activity in pro-populist Madrid through these documents enhances the heroic humanitarian work of the young Swiss philanthropist, who on 8 December 1936 almost lost his life when the French Embassy plane he was flying out of Spain was strafed by a Republican fighter. At the same time, this documentation delves into the abyss into which those who decided to end the lives of thousands of prisoners whose custody was the responsibility of Largo Caballero’s government.

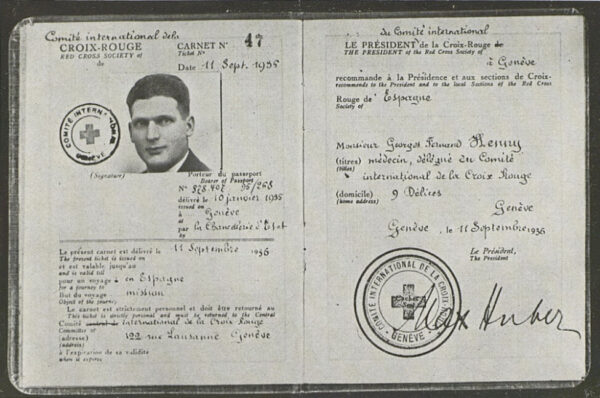

Born in Geneva, Henny was 29 years old, unmarried and a paediatrician at the cantonal hospital when the Civil War broke out. He had to seek permission from his authorities before agreeing to join the ICRC’s humanitarian mission in Spain.

The young doctor signed a one-month contract with the Red Cross, from 11 September to 11 October 1936, which could be extended month by month. His salary was 750 Swiss francs and he was covered by sickness and accident insurance worth 75,000 Swiss francs in the event of invalidity.

Henny will head the ICRC delegation in the capital under Marcel Junod, delegate general in Spain and chief delegate in the governmental zone. He arrived in Madrid on 16 September 1936, just as the rebels were about to take Maqueda (Toledo), 73 km from the capital.

The headquarters of the ICRC delegation was in a small palace at calle José Abascal 55, next to Paseo de la Castellana, where the sculptor Mariano Benlliure had his house-workshop. Very close by, at José Abascal 27, was the Norwegian legation, headed by its honorary consul, Félix Schlayer, which became a refuge for around a thousand persecuted people. Henny maintained a close relationship with Schlayer throughout his humanitarian mission in Spain.

Henny’s deputy delegate was Andrés de Vizcaya Laurent, 33, born in Baden-Baden (Germany) to a Spanish father and French mother, but settled in Barcelona as a businessman. Henny’s first contact in the capital was with the president of the Red Cross in Republican Spain, Aurelio Romeo Lozano, a paediatrician like himself and a civil servant in the Madrid City Council. The twenty or so volunteers who would work with Henny belonged to the Spanish Red Cross.

One of Henny’s first steps was to collaborate with the Chilean ambassador, Aurelio Núñez Morgado, to try to evacuate the women and children from the besieged Alcázar in Toledo. At the same time, he was in charge of the return from the rebel zone of the thousands of children who were enjoying the school summer camps when the military coup broke out.

Appeal for help to Geneva

Since its opening, hundreds of people have been queuing up at the ICRC delegation to secure the release of their relatives or to locate their whereabouts, as well as to contact loved ones left behind in the rebel zone. Between September and December 1936, the delegation received 21,800 requests for information. The prolongation of the conflict would bring the number of requests to 261,400 in 1937.

The fate of those imprisoned by the government forces soon became his main concern. As soon as he arrived in Madrid, on 22 September, Henny informed Geneva that “it is very difficult at the moment to obtain lists of prisoners and to systematically visit the prisons in Madrid, as Dr. Junod had asked me to do”.

The young Dr. Henny soon assumed his role in the face of the disasters of the war. On 30 September, he asked the ICRC in Geneva to make “an energetic and rapid intervention with the governments of Burgos and Valladolid [sic] so that the civilian population and prisoners of war would not be shot and so that the open towns where women and children were victims would not be bombed”.

On 7 October, Henny and his deputy Vizcaya were received by Manuel Azaña, President of the Republic. “He congratulated us on the humanitarian work we were doing and offered us his support”, Henny reported. Azaña asks them for news about his nephew Gregorio Azaña, arrested and shot in August by the rebels in Córdoba. “He may have been shot, but the President doesn’t know that,” Henny tells the CIRC.

On 15 October, Henny reiterates to Geneva his difficulties in obtaining the list of government prisoners, “as provided for in our work programme”. “As soon as I can be received, I will deal with this important question, although I have little hope of obtaining complete satisfaction,” he writes.

Visiting prisons, “very dangerous”

Henny will also visit prisons to inquire into the fate of detainees at the request of their families. He does this in consultation with the diplomatic corps stationed in Madrid. From the beginning, he was accompanied on these visits by Schlayer, who helped him as an interpreter, and Pérez Quesada.

The ICRC delegate immediately received “warnings of caution from friends who considered such steps to be very dangerous in the present circumstances”, as he reported to Geneva on 24 October on the occasion of his visits to the prisons. In this report, Henny reports that he “had the honour” of being received on the same day by the head of the government, Francisco Largo Caballero, to whom he asked for the release of the women detained in Madrid. The Socialist leader rejects the proposal because “he considers that all the women detained in Madrid are the subject of information and that there are no hostages in this city“.

Henny also raised the question of exchanges of non-combatant prisoners under the agreement signed on 3 September by the ICRC and his predecessor, José Giral, and ratified by Largo Caballero himself. The head of the government insisted to Henny that the exchanges should be carried out by the ICRC on its own initiative, avoiding the appearance of “an agreement between two belligerent governments”.

In another report, dated 28 October, Henny informed Geneva that there were more than 10,000 prisoners in Madrid prisons. “In some of them the prisoners were in deplorable conditions, in others the conditions were better”, he writes. He also reports again that he received “several discreet but quite precise warnings, giving me to understand that it was better for me to cease this activity”, alluding to his visit to the prisons.

Henny was also shocked to learn that “small political groups had free access to these prisons where they chose the prisoners they wanted. These people are then reported as disappeared”. He also reports that “on Sunday morning [25 October] more than 134 corpses were collected in the municipality of Madrid alone”. To demonstrate that “the facts I am telling you are not gossip”, he says that “I have personally had the opportunity to go out of the city in the morning and I have seen bodies abandoned in the vacant lots”.

We are looking – Henny continues – for ways to effectively guarantee the protection of prisons, but we can’t find them. We believe that the government feels overtaken by the political parties who really do what they want.

The Popular Front: there are no “hostages” but “political prisoners”

Henny also refers in his report of 28 October to the note that the British government had sent days earlier to the two sides proposing an exchange of the non-combatant prisoners, described in the note as “hostages”, in view of the risk that they would be exterminated en masse, for which it offered the services of the Royal Navy. The Republican government replied that in its zone there were no “hostages” but “political prisoners” who had been arrested “because of their direct involvement in the uprising against the Republic or because they might cause it harm and because of their relations with opponents of the regime”. Henny clarified to Geneva on this point that “it is the same answer I was given in my interview in the Presidency”, referring to his meeting with Largo Caballero.

For Henny, the distinction between political prisoners and prisoners of war mattered little “from a humanitarian point of view”. “We believe that political prisoners, in the present circumstances, are entitled to the same treatment, if not better, than prisoners of war,” Henny told Geneva on 30 October.

We must consider – continues the Red Cross delegate – that most of these so-called political prisoners have had no real political activity, but are detained because they had a right-wing relative, or simply a friend. On the other hand, among them there are a large number of women, and even elderly women who are entitled to some consideration.

This question is very relevant for a full understanding of the mentality that led to the massacres of prisoners by the Republican forces. The massacres had begun the day before this note by Henny, on 29 October, with the first “saca” [removal] of 31 prisoners from the Las Ventas prison, killed in the Aravaca cemetery, among them Ramiro de Maeztu and Ramiro Ledesma.

The criterion for considering political prisoners as prisoners of war was again defended by Henny before Largo Caballero himself in the letter he wrote to him on 2 November 1936, with a copy to Julio Álvarez del Vayo, Minister of State, with whom he had met five days earlier, and to Rodolfo Llopis, Undersecretary of the Presidency. The text was reviewed by the diplomatic corps accredited in Madrid.

I know that it may be objected – wrote the Red Cross delegate to Largo Caballero – that the persons detained in the Madrid prisons are not prisoners of war, but political prisoners. However, considering that they are deprived of their liberty because of the war, and by virtue of the Law of Nations and Article 3 of the Annex to the Hague International Convention of 18 October 1907, I consider that these persons are entitled to the same humanitarian treatment as prisoners of war, and I am sure that the Spanish Government is the first to recognise this.

In the same letter, Henny asked Largo Caballero to authorise him to visit the prisons and to promote prisoner exchanges. He also reminded him that the ICRC had asked his government for “lists of combatant and non-combatant prisoners held in government territory”. Henny guarantees that “such lists would only be communicated confidentially to Geneva in order to facilitate the International Committee’s requested enquiries about persons reported missing”.

Although the ICRC delegate reiterated his request “insisting in particular on the list of combatant prisoners”, he announced to Largo Caballero that he would shortly present “a project of double release based on exchange” for non-combatants.

With his letter, Henny was one day ahead of the appeal that ICRC President Max Huber would make to the two sides, in line with the British note, for the release or exchange of all non-combatant prisoners.

Without aspiring to so much, Henny is confident that his letter will get Largo Caballero’s government to improve the situation of the disaffected prisoners. “Even if I do not obtain complete satisfaction, I dare to hope that by this petition we will try to put a stop to the abuses that are committed daily in the prisons of Madrid,” he assures us. He was soon to be disappointed.

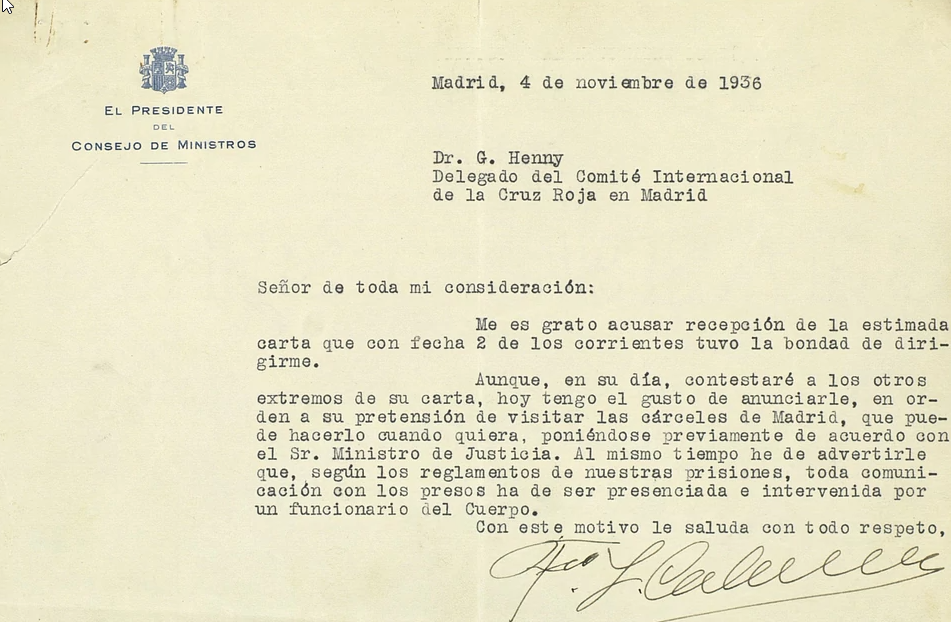

Largo Caballero replied to Henny two days later. He only agreed to his request to visit the prisons. As for the requests concerning the lists of prisoners and the exchange of non-combatants, Largo Caballero replied that “in due course, I will reply to the other points in your letter”. Henny never received a reply on these matters.

The silence of the head of the Republican government on the prisoners in his letter of 4 November is thunderous, given that, as we have said, the rounding up and killing of prisoners had already begun in the Las Ventas prison on the 29th, under the instructions of the Ministry of the Interior itself, which was also headed by the Socialist Ángel Galarza. These round-ups were to be extended to Porlier prison, under the same governmental cover, and then to the Modelo and San Antón prisons from the 7th, only three days after Largo Caballero’s reply to Henny.

The lists would be precisely, as was demonstrated in the midst of the sacas, the only instrument of control and verification in the hands of the Red Cross and the diplomatic corps to try to guarantee the lives or know the fate of the people detained in the prisons of Madrid, although for more than two thousand of these detainees it would already be too late.

The fact that Largo Caballero’s government not only refused to recognise the government detainees as prisoners of war, but also refused, as we now know, to respond to the Red Cross’s request for the lists of prisoners, is an important fact about the role of the Popular Front government in this sinister chapter of the Civil War.

By refusing to provide these lists to the ICRC delegate in Madrid, Largo Caballero further aggravated his responsibility along with all those who, obliged to guarantee the lives of thousands of people held captive in the prisons of the capital, collaborated by action or omission in the largest mass executions committed in the Civil War against unarmed people.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1648 Pedro II of Portugal is born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021