Text adapted from the magazine The Hispanic Roots of the United States published by of Asociación Cultural Héroes de Cavite. The magazine is free to download and we encourage you to read it and share it!

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed along the coast of California between 1542 and 1543, discovering San Diego and Monterey Bays. The beginning of Spanish Pacific Exploration was led by this Juan Cabrillo, long considered to be Portuguese but now known to have been born in Palma del Río, province of Córdoba, Spain. After his death resulting from a confrontation with the Indians, the expedition continued under the command of Bartolomé Ferrelo. It reached Cape Mendocino, named in honor of the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco, and sailed further north along the Oregon coast.

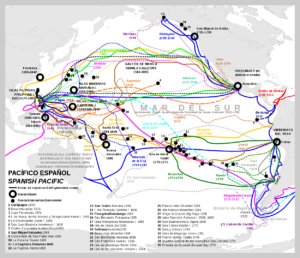

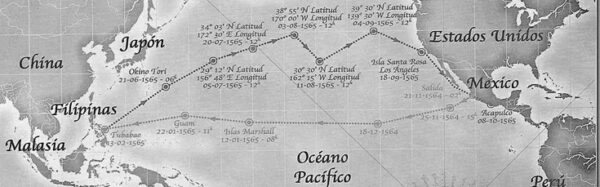

Since 1565, Spanish galleons crossed the Pacific between Acapulco and Manila once a year in each direction, marking the beginning of a financial and commercial globalization between Asia, America, and Europe. The trip from Acapulco to Manila took about three months with a stopover on the island of Guam, known until 1898 by its native name, Guaján. The voyage from Manila to Acapulco was a challenging journey that could take four to six months. Manila, founded in 1571, became the primary port for these voyages, although earlier most galleons operated from Cebu.

The galleons would cross the Pacific with no stopovers, and the first point on the American continent they sighted was Cape Mendocino. From there, the galleons made a relatively easy voyage, making use of the California Current. However, after the 1595 shipwreck of the San Agustín, a decision was made that the Manila galleons would no longer explore that coast and would instead transport their cargo directly to Acapulco.

The Manila Galleon Route

In 1602-1603, Sebastián Vizcaíno traveled the same coasts as Cabrillo, creating meticulous maps and landing several times in Alta California, renaming some of the places discovered by his predecessor. The maps created by Vizcaíno became essential when Visitador General of New Spain, José de Gálvez, prompted the expansion of Spain into Alta California in 1767 to counter the Russian advance from Alaska southward along the Pacific coast. As Sebastián Vizcaíno was compelled to turn back due to scurvy, Martin de Aguilar pressed onward, eventually reaching the Oregon coast, which he was the first to detail in his journal, marking a significant exploration milestone.

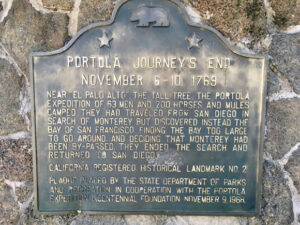

Gaspar de Portolá set out by land from San Diego Bay in 1769, seeking Monterey Bay, but instead discovered San Francisco Bay, which had gone unnoticed for over two centuries. The existence of this bay was unknown not only to Cabrillo, Ferrelo, and Vizcaíno but also to the Manila galleons, which had sailed those waters year after year.

The presence of Russians and English north of Cape Mendocino led to a series of Spanish naval expeditions in the North Pacific. The first expedition, captained by Juan Pérez Hernández with Esteban José Martínez as first officer, took place in 1774. Due to adverse meteorology and currents, the expedition’s results were limited, prompting further explorations.

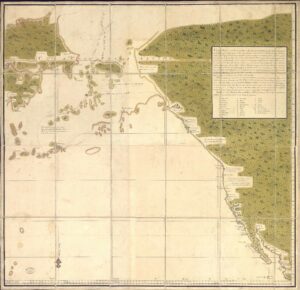

In 1775, the second expedition, commanded by Bruno de Heceta and including Juan Pérez Hernández, Juan de la Bodega y Quadra, and Francisco Antonio Mourelle, discovered and mapped the mouth of the Columbia River. They crossed the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the state of Washington. Shortly after, Heceta had to return due to scurvy, while de la Bodega and Mourelle continued to Alaska, discovering Bucarelli Bay.

The third expedition in 1779, under the command of Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán and including Juan de la Bodega and Francisco Antonio Mourelle, sought to assess Russian penetration into Alaska, search for the Northwest Passage, and capture James Cook, who had died in Hawaii earlier that year.

Reduced Chart of the Northern Coasts and Seas of the Californias formed to the 58th degree of latitude by the observations made by Lieutenant Don Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra and Ensign Don Francisco Antonio Mourelle.

The fourth expedition, captained by Esteban José Martinez, reached Nootka Island in 1788. Here, they established Fort San Miguel and the bastion of San Rafael. The Spanish flag flew there until 1795, after the signing of the third Nootka Convention; Juan de la Bodega represented Spain in its negotiations. Both nations provisionally renounced the sovereignty of that enclave.

Other expeditions continued to travel and map the North Pacific American coast to Alaska. The expedition of Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante (1789-1794), the most important Spanish scientific expedition of the 18th century, named the Malaspina Glacier in Alaska. They also came into contact with the Tlingit indigenous people, leaving numerous pictorial testimonies of the natives and the local flora and fauna. Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés went all over Vancouver Island. In 1791, Salvador Fidalgo built Fort Núñez Gaona (now Neah Bay) and named Cordova Bay (with a “v” and without an accent) and Port Valdez (Valdés). Manuel Quimper sailed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca. In 1792, Jacinto Caamaño thoroughly described the southern coast of Nootka and assigned Spanish place names. Finally, Francisco de Eliza and pilot Juan Martinez y Zayas reconnoitered the mouth of the Columbia River, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and San Francisco Bay. The Hispanic Monarchy continued to consider those Northwest territories to be its own until they were jointly occupied by Great Britain and the United States in 1818. In the end, Spain renounced its sovereignty in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1552 Battle of Bicocca.

- 1565 Miguel López de Legazpi founds Cebu as Villa de San Miguel.

- 1806 María Cristina de Borbón Dos Sicilias was born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021