Source:ABC

Although today there is controversy on the subject, several letters from the time reveal that the British Jeffrey Amherst proposed to deliver smallpox-infested blankets to the natives who besieged For Pitt in the 18th century.

Although it is hard to believe, biological warfare did not start in 1914 when, during World War I, the French used ethyl bromoacetate to force the Germans out of their trenches. According to Teri Shors (University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh) in her dossier “Viruses: A Clinically Oriented Molecular Study”, its origins date back to the 6th century, when “the Assyrians poisoned the water wells of their enemies with ergot of rye” and “the belligerent tribes catapulted the carcasses of sick animals over the castles to infect their opponents”.

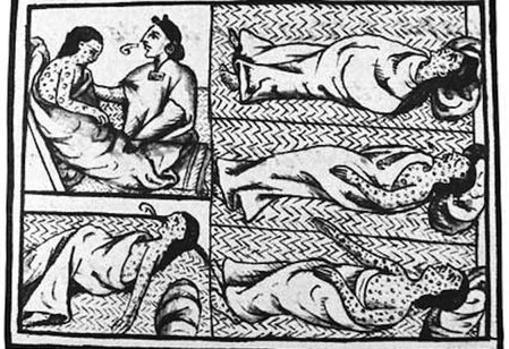

Therefore, it is not surprising that the colonists who traveled to the New World used biological warfare to defeat the Native Americans. Sometimes unintentionally (as happened in many cases with the Spanish conquerors) or, in many others, on purpose. In this sense, the greatest exponent of the use of disease to subdue a population was an English officer: sir Jeffrey Amherst. Commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America during the 18th century, this military man became infamous for having proposed to his subordinates to send the native smallpox-infested blankets to spread smallpox among the people besieging Fort Pitt in 1764.

Although the controversy over this action is still alive (there are many investigations that determine whether or not the blankets were delivered), what is clear is that Amherst sent a letter to his subordinate, Henry Bouquet, in which he urged the use of bacteriological weapons to decimate his enemies. An impossible-to-deny missive in which the soldier stated that “you would do well to try to infect the Indians with blankets, or by some other method” to “eradicate this execrable race”.

This practice, however, was also blamed on Francisco Pizarro’s men, as Shors himself and Charles Volcy (professor of biology in the department of the National University of Colombia) point out in “The Bad and the Ugly of Microbes”. However, experts such as Agustín Muñoz Sanz (head of the infectious pathology unit of the Infanta Cristina Hospital in Badajoz and professor of Infectious Pathology at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Extremadura) have denied over the last few years that Spain had not yet forged itself betting on spreading diseases in a premeditated way.

This practice, however, was also blamed on Francisco Pizarro’s men, as Shors himself and Charles Volcy (professor of biology in the department of the National University of Colombia) point out in “The Bad and the Ugly of Microbes”. However, experts such as Agustín Muñoz Sanz (head of the infectious pathology unit of the Infanta Cristina Hospital in Badajoz and professor of Infectious Pathology at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Extremadura) have denied over the last few years that Spain had not yet forged itself betting on spreading diseases in a premeditated way.

“The English and Dutch wreaked havoc among the natives of the American East Coast (present-day Massachusetts) by infecting and killing them with blankets contaminated with the smallpox virus. Spain did not carry out what we now call biological warfare, no matter how rudimentary it was,” explained Muñoz Sanz himself in an interview for the magazine ” Sinc. Science is news” (“Smallpox and measles were the perfect allies in the successful Spanish conquest of America”). In this interview, the expert added that, despite what the Black Legend has tried to expand, the reality is that the diseases that arrived from Europe were the ones that most natives took to the grave. Although involuntarily.

Towards the poisoned blankets

Getting to the moment in which Amherst sent this letter requires going back in time to the year 1760. This is what Alexis Diomedi (from the Hospital del Salvador Infectious Diseases Unit) states in his dossier “The biological war in the conquest of the New World . A historical and systematic review of the literature”. In it, he explains that, around the year 1760, the Ottawa Bwon-Diac tribe leader (known today as Pontiac due to a bad translation) declared war on the British and French settlers who had settled in the Great Lakes and the North American Middle East.

The fight allowed the tribe to obtain an armistice with the French that lasted several years. However, the same did not happen with the English troops, then under the command of Jeffrey Ambherst, who had arrived two years earlier to present-day New York as commander-in-chief of the British army. This is confirmed by Diomedi himself, who defends that these Europeans repeatedly abused the natives until 1763. That precise year, twelve tribes of Amerindians, including the Ottawa, the Chippewas, the Shawnee, the Mingo, and the Delaware, united to fight against the English settlers in Ohio.

From then on a conflict arose that, as the journalist, sociologist and history writer Gregorio Doval points out in his popular “Brief History of the American Indians”, stood out for its cruelty. The misnamed Pontiac, who had distinguished himself as a soldier under the command of the French shortly before, carried out a successful campaign by which he managed to defeat the English in the open field at Point Pelée, near Lake Erie. “After that, he besieged Fort Detroit, where he killed 56 whites, and 54 more in Bushy Run“, adds the author.

From then on, and despite the fact that the English government tried to draw the borders to avoid continuous massacres, the native incursions claimed the lives of hundreds of settlers.

Repeated attacks by the Indians elicited an even more brutal response from the English. “These incidents prompted the Pennsylvania Assembly to once again offer rewards to anyone who kills any enemy Indian over the age of ten, including women, a practice that had been useful during the Seven Years’ War. The war was brutal and the murder of prisoners, the attack on civilians, and other atrocities were continuous on both sides ”, adds Doval in the aforementioned work.

Fort Pitt

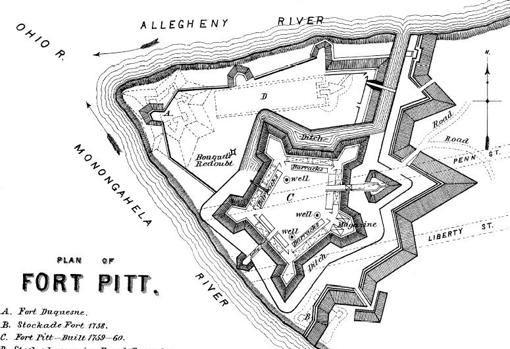

The so-called “Pontiac Rebellion” caused that, in mid-May, nine of the eleven British forts in the region had fallen into the hands of the natives. And the situation was no better for the other two (Fort Pitt and Fort Detroit), who remained under siege. “Fort Pitt, located at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, was under the command of Captain Simeon Ecuyer, who reported its situation to Colonel Henry Bouquet in Philadelphia. He, in turn, reported to General Amherst“, adds Diomedi in his investigation.

As historian Elizabeth Fenn explains in her article “Biological Warfare in 18th Century America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst”, Ecuyer reported on June 16th to his superior that the situation was dire for civilians and merchants who took refuge inside the fort. Not only because of the enemies surrounded its walls, and hunger, but because inside there was an outbreak of smallpox. After receiving this letter, Bouquet forwarded the information in turn to Amherst. As he explained, they needed reinforcements to be able to survive and for the fort not to fall into enemy hands.

To this day it is perfectly documented (the letter is still preserved) that Amherst proposed to his subordinates to use this disease to undermine the natives, whose resistance to European ailments was much lower. This is how Juan F. Jiménez and Sebastián L. Alioto recall it in their dossier “Confinement policies and the impact of smallpox on the native populations of the Pampas-North Patagonia region (1780s and 1880s)”: “The isolation of those populations from the inhabitants of the Old World, made endemic and less lethal diseases on the other side of the ocean became epidemic and highly destructive in American lands. Smallpox outbreaks, in particular – though not solely – decimated the natives on a regular and recurring basis”.

The answer was the following, according to Patrick J. Kieger in his report “Did the colonists give infested blankets to Native Americans as biological warfare?”:

“Couldn’t we find a way to infect these disgruntled Indian tribes with smallpox? We must, in this case, use a stratagem to reduce them.”

The idea pleased Bouquet, who sent him the following response on July 13th:

“I will try to inoculate them with some blankets that fall into their possession, being careful not to contract the disease myself”.

On July 16th, the commanding general sent another letter to his subordinate. The content, which varies depending on the expert you turn to, would be the following according to Diomedi:

“You would do well to try to infect the Indians with blankets, as well as try to use any other method that may serve to eradicate this abhorrent race”.

Reasonable doubts, real epidemic

From this point on, the story fades. A good part of the experts affirms that the delivery of blankets was carried out by order of Amherst. However, Kieger is in favor of the fact that the real culprit was a merchant and militia captain named William Trent. He would have written on June 23rd that he took advantage of the exchange of gifts between factions during the visit of two high tribal dignitaries to the fort to deliver “two blankets and a handkerchief” as a poisoned present. “I hope it has the desired effect”, he explained in his diary.

Fenn claims that days later the merchant sent the Army an invoice for these three objects “to replace kindly those that were taken from people in the hospital to transmit smallpox to the Indians”. The army command accepted and paid the money. However, by then Amherst had already been replaced as colonial commander by Thomas Gage. In any case, what is clear is that – whether it was Trent or not – there is documentation that certifies that this plan was orchestrated. Although, according to historians such as Paul Kelton, it is not clear to this day whether Bouquet gave orders to his men to spread smallpox or not.

In this sense, Diosmedi recalls that, according to several authors, this practice was not strange for the English. “The British army had been systematically spreading smallpox among the Indians since 1755, in connection with the outbreak that decimated the Potawatomis in 1757, then allies of the French, their adversaries in the colonization of North America”, he reveals. Beyond doubts, in the years after the incident a smallpox epidemic spread among the natives near Fort Pitt.

This was confirmed in April 1764 by Gershom Hick, an explorer captured by local tribes just a year earlier. “Smallpox has been rampant and furious among Indians since last spring and that thirty or forty Mingos, Delaware, and a few Shawneese have died of smallpox since then, whilst it is still among them”. However, many other authors are in favor of the fact that the disease could have spread through other sources. Many others also believe that Trent would have boasted in his diary that his plan had worked if it had been successful.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021