Source:Fundación Disenso

On the day of 19 July 1808, one of the most important open field clashes in Spanish history took place: the Battle of Bailén. Taking advantage of the 213th anniversary of the start of hostilities on that battlefield near the town of Bailén in Jaén, Spain, this article aims to describe the main events of the aforementioned battle.

The battles of Vitoria and San Marcial, which took place in June and August 1813 respectively, may be two of the best-known clashes of the Peninsula War due to their political repercussions. However, in the early stages of the war, specifically on 19 July 1808, one of the most important open field clashes of the period took place: the Battle of Bailén.

Background: The military and political context on the Peninsula

News of the 2 May uprising in the capital soon spread throughout the nation. Barely three weeks after the events in Madrid, other insurrections broke out in different parts of Spain. Local Juntas that did not recognise the abdication of Fernando VII were also formed and challenged the authority of Napoleon I by recruiting troops. To better coordinate political and military decisions, the Central or Supreme Junta was set up in Seville and declared war on France on 6 June 1808. Instructions were immediately issued to recruit soldiers, especially in the region of Andalusia because the French armies were not yet present in that territory.

At the beginning of the war, the Spanish army numbered about 100,000 men. Excluding the 20,000 troops of the Marquis of La Romana, that were in Denmark, and the 9,000 men garrisoned in the Balearic archipelago, the number of soldiers available was therefore drastically reduced: some 30,000 men in Andalusia, specifically in the garrisons of Cádiz and Gibraltar, and a further 27,000 soldiers quartered in Galicia, the region to which they had moved after the invasion of Portugal in October 1807. However, the location of these forces was scattered: the traditional enemy had been England, so the armies were designed to defend against possible invasions or landings at coastal points, but not to fight an enemy that already occupied the centre of the peninsula.[sup1sup]

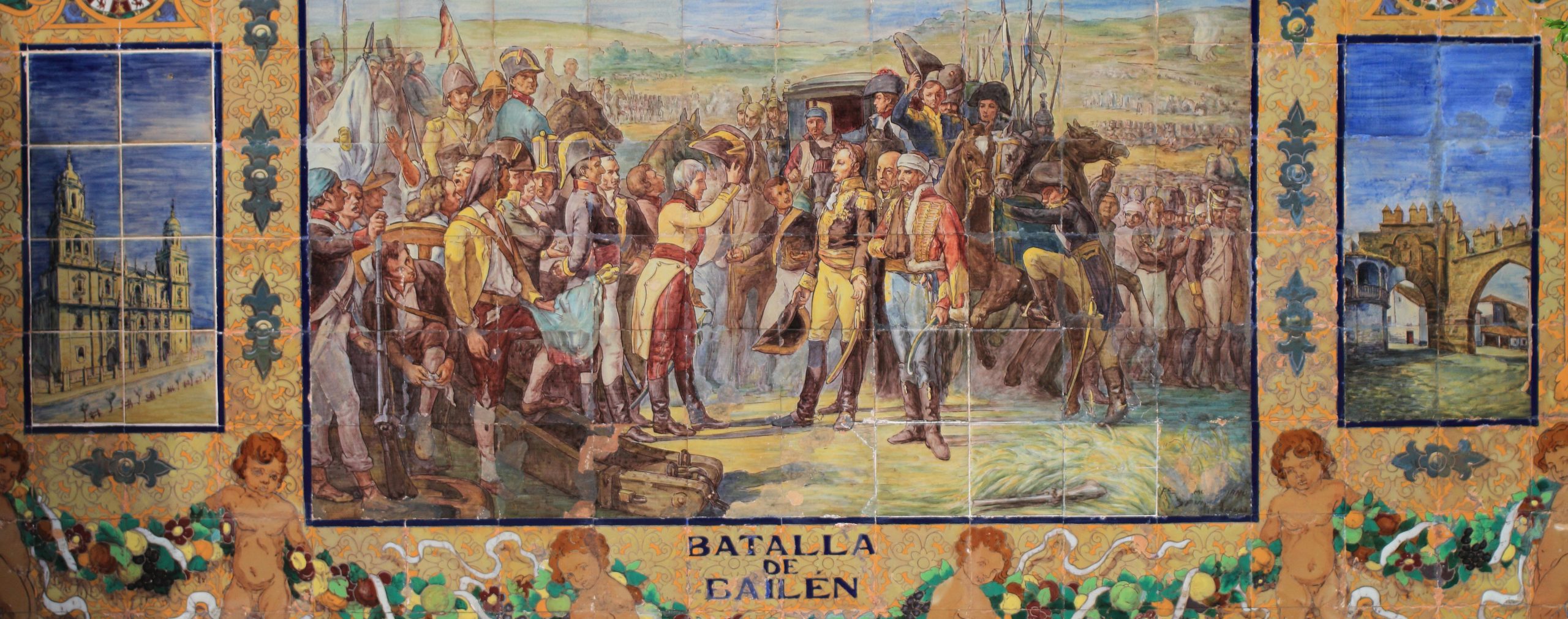

Episode of the Battle of Bailén by Ricardo Balaca y Orejas Canseco. Image copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado

Under the Treaty of Fontainebleau signed between Spain and France in October 1807, French armies were able to cross the Pyrenees to undertake the conquest of Portugal. Once the annexation was completed, the troops remained on the mainland. The French army had a similar number of forces to the Spanish army and was composed of five army corps and a detachment belonging to the Imperial Guard. The French forces were located throughout Pamplona, San Sebastián, Madrid, Toledo, part of Aragon, Old Castile, Catalonia and Lisbon.

Following the declaration of war on France announced by the Junta Suprema de Sevilla on 6 June, the Emperor ordered his generals to neutralise the two largest Spanish contingents located in the regions of Galicia and Andalusia. French Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières, with just 13,000 men, managed to defeat the 25,000 soldiers from Galicia led by Spanish General Joaquín Blake y Joyes at the Battle of Medina de Rioseco (Valladolid).

With the situation in the north resolved, the French turned their attention to Andalusia. The offensive was led by Major General Pierre-Antoine Dupont de l’Étang. Napoleon was confident that his lieutenant could quickly control and quell the insurrections in Cordoba and Seville and neutralise the Spanish forces in the region. To achieve his goal, the emperor appointed 20,000 troops[sup2sup] under the general’s command and felt deeply confident of success: if Bessières had succeeded in destroying a vastly superior armed contingent, Dupont would be able to defeat any enemy put in front of him. But, as Chandler notes, “he was in for an unpleasant surprise, disaster was looming over the French”.3

Dupont’s campaign in Andalusia and the “Porcuña plan”

With these strategic objectives in mind, on 31 May the French general crossed Despeñaperros with the intention of reaching Córdoba. On 7 June, after an uneventful march through La Carolina, Guarromán, Bailén and Andújar, there was a brief clash at the Alcolea bridge, which forced the Spanish garrison in the city to retreat to Écija. Nothing now stood in the way of Dupont and his corps, which demolished the New Gate in the wall of Córdoba and began a brutal sacking, breaking into all kinds of religious and private buildings in the city.4 Meanwhile, news that the juntas of Seville and Granada were forming an army did not go unnoticed by Dupont, indeed, rumours reached him that the Spanish forces numbered more than 50,000 men. Faced with this situation, he considered that the most correct course of action would be to wait for reinforcements from Madrid and move from Córdoba to Andújar, which he reached on the 18th. In this position, he believed he was safe because of its strategic position between two rivers (the Jándula to the west and the Guadalquivir to the south).5

Dupont was convinced that Francisco Javier Castaños, commander-in-chief of the Spanish forces, would attack Andújar. However, he could not have been more mistaken: the Spanish were contemplating another, much bolder strategy. Indeed, the Army of Andalusia, which actually numbered 29,000 troops and 28 artillery pieces,6 did not consider the option of attacking Andújar, as it would have entailed heavy casualties. In these circumstances, on 12 July Castaños’ army concentrated in the town of Porcuña in Jaén, where they devised a plan of attack ─known as the “Porcñna plan”─ which consisted of a large overflow movement through the enclaves of Mengíbar and Bailén to break Dupont’s communications with Madrid, and thus force the French officer to abandon his position in Andújar and present battle.7

Castaños ordered Theodor von Reding, commanding the 1st Division, to proceed to Mengíbar, south of the Bailén position, on the 14th in order to make an attack on the 16th and attempt to occupy Bailén. To do so, he would also have to count on the support of the field marshal and commander of the 2nd Division, the Marquis de Coupigny, who would also attack the French positions in Bailén, but from Villanueva. Meanwhile, General Castaños, with the remaining divisions, ─the 3rd Division led by Field Marshal Félix Jones and the Reserve Division commanded by Lieutenant General Manuel de la Peña─, would simulate several attacks on Andújar to distract Dupont and thus make the French general hold his ground, that is, to believe that the Spanish had the real intention of attacking him in the vicinity of the aforementioned enclave.8 He also ordered the detachments of Cruz Mourgeon and Pedro Valdecañas to position themselves on the enemy flanks to harass the French.

Dupont, faced with this situation, sent a messenger to Vedel requesting reinforcements, so the general set out for Andújar on the morning of the 14th. Meanwhile, Field Marshal von Reding, without showing his real forces (he advanced with only two battalions), began his attack on the positions of Mengíbar, which was under the control of the French general Liger-Belair. The clash forced the French to retreat, but Vedel, who was informed of the Spanish movements, came to his aid on the night of 14-15 July, triggering a heavy firefight that ceased at 08:00. Vedel then decided to withdraw to Bailén to stock up on supplies and resume the march to Andújar. He left only one battalion as a reinforcement, considering that Reding’s forces were in fact very small.9 At nightfall on 17 July, Vedel again received orders from Dupont to return immediately to Bailén and reinforce the positions at Guarromán and La Carolina, enclaves he reached on the evening of 18 July with some 8,000 men.

Meanwhile, Reding’s and Coupigny’s divisions, who probably knew beforehand that the French had abandoned the enclave, took Bailén without having to fight on the morning of 18 July. In all, they totalled more than 17,000 troops and 23 artillery pieces, so Dupont, who had just received word from his scouts that Bailén had been occupied by Spanish forces, was now in dire straits: his communications were completely cut off and he had no choice but to abandon his position at Andújar, engage the Andalusian Army at Bailén to try to reopen his lines of communication and await reinforcements from General Vedel. These troops, however, never arrived because, at the time, the distance separating the two generals was, according to Chandler, approximately 48 kilometres.10

The glorious day of 19 July

After setting out from Andújar at 21:00 on the 18th with approximately 13,000 troops and 27 artillery pieces, the vanguard of the French army led by Commander Teulet crossed the Rumblar River bridge without resistance. At 03:00 on the 19th, one kilometre north of its positions, near the Zumacar Chico hill, it encountered a company of Walloon Guards, who were occupying the Ventorrillo del Rumblar (a small inn) and surrounding positions. Fighting ensued and the company was forced to retreat, which alerted the Spanish vanguard led by Brigadier Francisco Venegas. Venegas, for his part, decides to block the French advance by stationing troops on the hill of La Cruz Blanca.11 General Reding, who was outlining instructions to his lieutenants to march towards Andújar and attack Dupont’s position with Castaños from two fronts, ordered immediate deployment and prepared for battle. Specifically, Reding and Coupigny’s Spanish army formed up in two lines composed of two wings and a centre in which most of the artillery was deployed.

As can be seen, Reding believed that Dupont remained in Andújar, but disinformation was also notorious on the French side. Dupont had always maintained the certainty that the bulk of the Spanish forces were south of the Andujar positions, beyond the Guadalquivir, and that the Spanish forces to the east were no more than small detachments that posed no serious threat. In this sense, what we find in reality is that neither side expected a large-scale confrontation in the vicinity of this town of Jaén.

In order to drive the French from their position on the hill of La Cruz Blanca, Reding ordered a joint attack from two directions: Venegas led from the north, while Brigadier Pedro de Grimarest attacked from the south. The Spanish were successful and captured two French artillery pieces. Shortly afterwards, however, a French counter-attack led by Teulet regained the position, although, due to their numerical inferiority, they eventually opted to retreat in an orderly fashion towards the Rumblar positions.

Dupont, who is aware of his subordinates’ fighting, is not yet aware that he is facing more than half the Army of Andalusia, so he decides to keep the formations in column and try to break the Spanish lines with Teulet’s vanguard and the squadrons of General Maurice Ignace Fresia’s 2nd Cavalry Division. The only thing on his mind is to restart the march as soon as possible to rejoin Vedel and get as far away as possible from Castaños, whom he still considers the main threat.

Dupont then ordered Brigadier General Théodore Chabert, in command of three battalions, and Brigadier General Privé’s cavalry brigade to advance on the Rumblar line. At 6:30, Dupont deploys 4,500 soldiers and 10 artillery pieces (waiting for the brigades of the Swiss generals Joseph Pannetier and the Count of Schramm, who had been left behind escorting the convoy with the loot from the sack of Cordoba, as well as the transport of the wounded and sick); but he was faced with a terrible reality: the Spanish forces in front of him were actually more than half the size of the Andalusian Army, and they outnumbered Dupont’s.

In view of the circumstances, the French general had no choice but to attack before Castaños arrived from the rear and was completely surrounded. Until midday, up to four attacks were to follow, most of them directed against the centre of the Spanish formation. All of them would be repelled, with great effort, by the Spanish infantry lines, which will suffer heavy casualties as a result of the cavalry charges of the French cuirassiers. However, the balance was tipped in favour of the Spaniards due to the action of the artillery, which, with a larger calibre than the French, reduced the enemy columns and forced them to retreat to their initial positions.

At 12:00, in a last desperate attempt to break through the Spanish lines, Dupont forms a large column with the elite troops of his army, the Marines de la Garde, positioned in the vanguard. Dupont and his generals take the lead in the attack and rush against Field Marshal von Reding’s centre. The Spaniards, far from being intimidated, concentrated all their artillery firepower on the French columns, which were again forced to hold off the attack. In addition, Dupont was wounded and finally ordered to fall back to the initial position, i.e. the hill of La Cruz Blanca. At the same time as the French attack on the centre of the Spanish positions, General Schramm advanced on the hill of Haza Walona, which was defended by the Swiss Reding Regiment No. 3 on the left flank. Schramm’s two regiments, which were mostly made up of soldiers of Swiss origin, refused to attack their compatriots and decided to go over to the Spanish side. In these circumstances, General Dupont has no choice but to retreat with the few French units he had under his command.12

At 13:00, Lieutenant-Colonel Cruz Mourgeon’s detachment appears in the French rear and left flank. Dupont, who actually believes he is the vanguard of Castaños’ army, decides to ask Reding for a ceasefire and permission for his troops to withdraw through Bailén. The field marshal agrees to the first demand, but refuses the second request, as it is up to his commander-in-chief to make the most appropriate decision in this regard. At 14:00, the vanguard of General De la Peña, in command of the Reserve Division of the Andalusian Army, crossed the Rumblar river ready to attack the enemy rearguard. Dupont, for his part, ordered a messenger to go to De la Peña’s position to inform him that a ceasefire had been declared and implored him to suspend the attack. Finally, negotiations began to define the terms of the capitulation, a process that lasted until 22 July.

With regard to the number of casualties on the opposing sides, Colonel Sañudo Bayón, based on documentation from the National Historical Archive, maintains that the Spanish side suffered 192 dead, 664 wounded and 1013 missing, i.e. a total of 1869 casualties, while the Imperial side suffered 1,800 casualties between dead and wounded. The rest of the French forces, around 20,000 if one adds those of General Vedel’s division, who decided to surrender along with their commander-in-chief on 24 July, were taken as prisoners of war.13

Under the capitulations, signed on 22 July 1808, it was decided that the French army – consisting of Dupont’s 8,242 soldiers together with the 9,393 troops of Vedel’s and Dufour’s divisions14 – would be repatriated to France. They would be taken to the ports of Rota and Sanlúcar to embark, and would then be disembarked in the port of Rochefort. The Spanish army was also to escort and guarantee the safety of the French soldiers during the journey to the aforementioned ports. Everything seemed to be going according to plan, but the fate of the prisoners changed radically.

The Junta Suprema de Sevilla, at the behest of the military governor of Cádiz, Tomás Marla, refused to evacuate the French. Pressure from the people, who demanded revenge for the sack of Córdoba and, above all, interference from England, which wanted to prevent the French army from fighting again in the future, meant that the Army of Andalusia would not allow the repatriation of the prisoners, except for the officers.15 Because the terms of surrender were not met, the French soldiers had to endure, until the end of the war, dreadful captivity on the island of Cabrera, where thousands of them died of starvation.

Consequences of the battle

If there has been one decision that has been the subject of much historiographical debate, it was undoubtedly the French general’s decision to remain in Andújar for almost a month. It is possible that Dupont, a veteran officer who took part in the decisive battles of Austerlitz and Jena, could not accept the failure to pacify the Andalusian region. This is probably why he fell prey to reckless indecision that ultimately led to the doom of his army and the total failure of the French campaign.16

Be that as it may, the fact remains that the Spanish victory at Bailén not only allowed the war effort to continue but also triggered many of the events that fall within this momentous period in Spanish history. Indeed, Moreno Alonso argues that without the Spanish victory in this confrontation “the Cortes would not have met in Cadiz, nor would the process prior to the convocation, which took place in Seville, have taken place”.17

But the interest of the battle lies not only in the military and political effects that the Spanish victory managed to forge on the peninsular territory but also in the terrible consequences that, from the international point of view, it had on the reputation of invincibility that the Grande Armée had maintained up to that time. In this sense, the belligerent powers of the continuous Coalition Wars renewed their hopes and again took up arms (the Fifth Coalition) in an attempt to counteract the hegemony that the French Empire had established on the continent. The importance of Bailén is therefore decisive if we wish to study not only the Peninsula War, but also the evolution of the Napoleonic Wars in the rest of Europe.

In short, the Battle of Bailén further ignited the fuse of a war that had different characteristics from those with which Napoleon – who was forced to intervene personally in the Peninsula after his brother, Jose I, decided to abandon Madrid and retreat to the Ebro in the face of the advance of General Castaños – had to contend in other European states. A conflict in which victories in battle were not going to lead to a decisive peace, as happened after the French victories at Austerlitz and Friedland, but to an escalation of the conflict. In fact, the enemies of the Napoleonic Empire were not only the bayonets, sabres and cannons of the Spaniards but also the irreducible patriotic commitment of a people who, together with Anglo-Portuguese aid, eventually succeeded in expelling the French armies from the Spanish mainland and bringing about the return of Fernando VII.

Notes

- Emilio DE DIEGO: España, el infierno de Napoleón, La Esfera de los Libros, Madrid, 2008, p. 213.

- Colonel Sañudo Bayón notes that the II Corps of Observation of the Gironde led by Dupont was made up of 21,776 men, 4,798 horses and 40 cannons. See Juan José SAÑUDO BAYÓN: «La batalla de Bailén: mitos y errores históricos». En Francisco ACOSTA RAMÍREZ (coord.): Bailén a las puertas del bicentenario: revisión y nuevas aportaciones. Actas de las séptimas jornadas sobre la batalla de Bailén y la España contemporánea, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, 2008, p. 79.

- David CHANDLER: Las campañas de Napoleón. Un emperador en el campo de batalla: de Tolón a Waterloo (1796-1815), La Esfera de los Libros, Madrid, 2005, p. 658.

- Emilio DE DIEGO: España, el infierno de Napoleón…, p. 221.

- Ibid., p. 222.

- Emilio DE DIEGO: «La formación del Ejército de Andalucía», Desperta Ferro: Historia Moderna, 45, Desperta Ferro, (2020), p. 17.

- Juan José SAÑUDO BAYÓN: «La batalla de Bailén: mitos y errores históricos»…, p. 85.

- Jean-Marc LAFON: «La acción de Mengíbar y el cerco al ejército francés», Desperta Ferro: Historia Moderna, 45, Desperta Ferro, (2020), pp. 28-30.

- Emilio DE DIEGO: España, el infierno de Napoleón…, p. 234.

- David CHANDLER: Las campañas de Napoleón…, p. 659.

- Rafael VIDAL DELGADO: «La batalla de Bailén». En la batalla de Bailén. Actas de las primeras jornadas sobre la batalla de Bailén y la España contemporánea, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, 1999 ,p. 71 y ss.

- Rafael, VIDAL DELGADO: Operaciones en torno a Bailén (la caída de los mitos), Foro para la Paz en el Mediterráneo, Málaga, 2015, pp. 316 y 317.

- Juan José SAÑUDO BAYÓN: «La batalla de Bailén: mitos y errores históricos»…, p. 96. On the other hand, Emilio de Diego points out that “the outcome of the confrontation was clearly favourable to Reding’s men. In the French ranks, there were some 2,600 casualties ─of which 2,200 dead and the rest wounded─, and in the Spanish ranks 978 ─243 dead and 735 wounded─”. Véase Emilio DE DIEGO: España, el infierno de Napoleón…, p. 238.

- Emilio DE DIEGO: España, el infierno de Napoleón…, p. 241.

- Vicente RUIZ GARCÍA: «El destino de los prisioneros. La odisea de los soldados derrotados en Bailén», Desperta Ferro: Historia

Moderna, 45, Desperta Ferro, (2020), p. 53. - It should be borne in mind that Dupont’s decision was based on two different motives: military and personal. On the military level, because Dupont, according to Sañudo Bayón, “did not consider Andújar to be a position to defend, other than as his base from which to continue the occupation of Andalusia”. Véase SAÑUDO BAYÓN: «La batalla de Bailén: mitos y errores históricos»…, p. 84. Finally, there were the officer’s own personal motives: according to the French historian Jean-Marc Lafon, a decisive victory in the region could have facilitated Dupont’s promotion to Marshal of the Empire. See Jean-Marc LAFON: «La acción de Mengíbar y el cerco al ejército francés», Desperta Ferro: Historia Moderna, 45, Desperta Ferro, (2020), p. 27.

- Manuel MORENO ALONSO: La batalla de Bailén. El surgimiento de una nación, Sílex, Madrid, 2008, p. 19.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1648 Pedro II of Portugal is born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021