Source:Medigrafic

Paper presented at the V Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Historia y Filosofía de la Medicina, Querétaro, November 1998

Exclusive hospitals for attention to sick natives were founded in New Spain. The most important of these were established by Franciscan missionaries at the Valley of Mexico and by the Agustinians in Western Mexico. In addition, foundation of the hospitals towns at Michoacan’s bishop, designed by Don Vasco de Quiroga, were based on the utopic and humanistic ideas of Thomas More. In this article we offer a revision of their origins, their multiple forms of economic support, the administrative operation, hospital organization with the extraordinary participation of the Indian natives the trust deposited in these institutions by the users, the peak and consolidation in the 16th and 17th centuries, as well as decadence and cancellation in the 19th century.

Introduction

After the European invasion and conquest of continental America, the consolidation of the Spanish colonial enterprise was completed in the ideological field by a group of men belonging to various monastic orders, among them Franciscans, Augustinians and Dominicans.

Some of them, influenced by the theses of Renaissance utopias, carried out extraordinary collective projects in the newly colonised indigenous peoples in Mexico.

The massive foundation of hospitals in the 16th century was one of the most successful strategies of the Catholic missionaries. The creation of infirmaries and hospitals in Mexico City, Xochimilco, Texcoco, Acámbaro and other places by the Franciscans, and the hospital towns in Michoacán by Don Vasco de Quiroga, demonstrate the vision, transcendence and importance of the religious and humanitarian work that guided these men (Figure 1).

Faced with novel situations, the missionaries implemented with pragmatism, altruism and enormous sensitivity, a series of socio-political and socio-cultural transformations, the consequences of which can still be perceived in the indigenous peoples they benefited. In this sense, M. León-Portilla refers that:

… the natural realities of the conquered country and the social and cultural realities of its native inhabitants, forced in many cases to modify and adapt the institutions that were intended to be implemented and even sometimes, to design others, in which the indigenous element and the new circumstances were widely taken into account …1

For the last three years we have been investigating the socio-cultural criteria for guaranteeing sufficient quality of medical care in public and private hospitals located in the indigenous villages of Mexico and other Hispanic American countries with a high percentage of native population.

Among other indicators, we are looking at the use of the indigenous language, the use of local foods, the relationship with traditional therapists, the application of herbal therapeutic resources, the use of local furniture, the hiring of indigenous personnel, and so on.

What happens when trying to apply these indicators in the indigenous hospitals founded by the Spanish during the viceroyalty?

In the following lines we will summarise the main findings from the compilation, reading and analysis of well-known works on the history of hospital medicine in Mexico. We refer to the works of Enrique Cárdenas de la Peña2, Donald Cooper3, Josefina Muriel,4 Marcela Suárez5, Carmen Venegas6, Benedict Warren7, and Antonio Zedillo8, who studied and reviewed Spanish documentation, while Miguel León Portilla – with wisdom and erudition – also draws on original indigenous sources.

General historical background

During pre-Hispanic times, there is no documentary or material evidence of specialised buildings to house the sick. Based on the assertion – not supported by documentary sources – of Dr. Francisco Flores in his Historia de la Medicina en México that: “the Aztecs had something similar to our hospitals”, C. Venegas is inclined towards the existence of hospital spaces in Tenochtitlan9, however, León-Portilla shows his disagreement because:

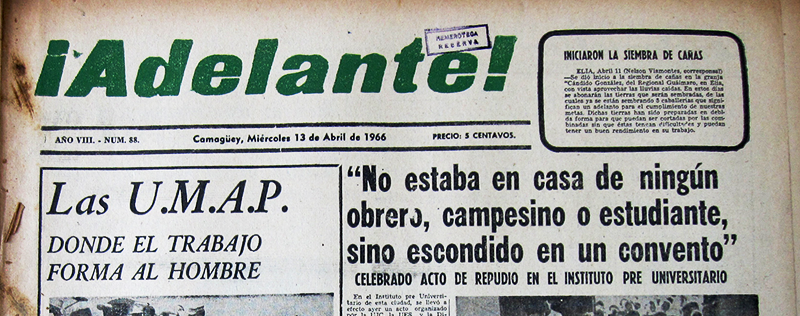

Although Alonso de Molina includes in his Vocabulario the word cocoxcalli, “house of the sick”, as a correspondence of “infirmary, hospital”, it has not been possible to document -as far as I know- the use of this word in any testimony of the pre-Hispanic tradition in Nahuatl10. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Tlacuilo’s version of the hospital for Indians in the Codex Osuna.

What is fully documented is that upon the arrival of the Spaniards, they began to build hospitals similar to those existing in Europe. The conquistador Hernán Cortés himself ordered the first hospital for the care of Spaniards and indigenous nobility. But it was the Franciscans who were the first to establish an infirmary for the poorest indigenous people in Mexico City in 1529, which later became the Real Hospital de San José de los Naturales in 1553. On the other hand, Don Vasco de Quiroga would multiply hospital establishments throughout the west of the country, creating hospital towns but also simpler facilities.

Reasons for the opening of hospitals

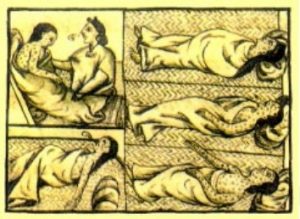

The aftermath of the bloody struggle of conquest, the outbreak of epidemics with diseases unknown in the American world (such as smallpox, measles and others), the intial colonial rule based on abuse, violence and exploitation of indigenous labour, and the recurrent famines in the urban centres of New Spain, led to one of the most dramatic demographic catastrophes of the last 500 years (Figure 3).

Thus, the high morbidity and mortality of the native population in the 16th century produced a significant loss of labour force that affected the economic interests of the newly arrived conquistadores. Associated with this was the spiritual conquest of the Indian peoples, whose idealistic expression of charity, beneficence and the realisation of Renaissance utopias was mixed with the compulsive conversion of the Indians to the new Judeo-Christian religious forms.

It is in this context that hospitals appeared as novel centres of healing but also as spaces of conversion to Christianity, that is, as instruments of social, ideological and even political control. Thus:

The priests recommended as a suitable means to convert them [the indians] to the new religion and adapt them to Spanish life, founding hospitals where it was easy to achieve religious and political ends11.

In 1541, Emperor Carlos I ordered the construction of the hospitals:

We order and command our Viceroys, Audiences and Governors to take special care to provide that hospitals be founded in all the Spanish and Indian towns in their provinces and jurisdictions, where the sick poor can be cured and Christian charity can be exercised12.

Figure 3. The dreaded epidemics that afflicted hundreds of Indians hastened the founding of hospitals exclusively for them. Florentine Codex.

In May 1553, the heir Felipe II in a royal decree indicated the installation of what would be the most important hospital for Indians in New Spain: … it is very necessary that in the city of Mexico there should be a hospital where the poor Indians can be cured, because when they fall ill there is nowhere to cure them, nor where to keep them who come from outside13 (Figure 4).

With a broader vision, and with the aim of concentrating the material and spiritual life of previously dispersed Indian families and communities, Don Vasco de Quiroga managed to create his hospital-villages in Santa Fe de Mexico, Tzintzuntzan, Santa Fe de la Laguna, among many other places. By the census of 1681, the Bishopric of Michoacán (which also included the present-day states of Guanajuato, Colima, and part of Jalisco, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas and Guerrero) had 254 hospital establishments14. In all cases, the hospitals constituted links in a chain that aimed at the complete social control of the Indians. Nevertheless, the establishment of the hospitals was an interesting strategy for dealing with the complexity of the indigenous problem of the time, a concept which, by the way, began to be coined in the viceroyalty as an expression of the conflict that the intense presence of the Indians meant for the privileged class.

Economic support

The sources of funding were multiple. At the beginning, the main one was the donation in money and in kind from the Spanish crown. Other resources came from the town councils that expropriated productive and uncultivated land, donations from wealthy individuals, inheritances or through important voluntary contributions such as those made by Vasco de Quiroga.

No less important were the support and donations from the Indians themselves. While the indigenous nobility gave property, livestock, mills, fulling mills, looms and other possessions, the Macehual Indians contributed their handicraft products and their very poor alms, which, when added together, meant a strong and magnificent income15.

By the end of the 18th century, the annual and obligatory indigenous tributes (which amounted to half a real) became the main sources of income. For example, in the Hospital Real de Naturales in 1778, such a tax accounted for 62% of total revenues, while rentas accounted for 28%, censos and printing 6%, and the caja real only 3.7%16.

Administrative organisation

Hospital administration varied according to the socio-political conditions prevailing in each region of the country, the religious order involved, the stipulations of the internal ordinances and regulations, and – of course – the complexity of the hospital in question.

Figure 5. Physical destruction of the Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales in this century for the extension of Avenida San Juan de Letrán, today Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas.

Thus, the highest-ranking and most obviously privileged was the Royal Hospital of San José de los Naturales17. At the highest level of its organisation was the Royal Board of Trustees, which included the viceroy but not the civil and ecclesiastical authorities based in Mexico City. The Board appointed solvent persons (e.g. doctors, bachelors or priests) to the posts of steward and administrator.

It also selected the medical and nursing staff. In turn, the administrator had the services of a notary and an accountant.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the participation of the brotherhood of Saint Hippolyte was requested, improving the hospital care on a temporary basis, since by 1730, due to the licentious life of its members, it was necessary to replace them with secular servants. By 1778, the ordinances of the Royal Hospital created by Viceroy Antonio María Bucareli established a reorganisation in which the Hospital Board, in addition to the steward and the administrator, established the existence of 4 university doctors, 4 surgeons, 10 major practitioners, several minor ones, 2 senior nurses (male and female) an undetermined number of junior nurses (both male and female), 2 maids, 9 to 10 waiters, 2 mattress makers, 2 cooks, several tortilla makers, atoleras and kitchen porters, a supplier with his assistant, a sweeper, an apothecary, a porter, at least four chaplains and a sacristan18.

Most of the support workers were indigenous19. And this was also the case in the simpler hospitals where the Indians themselves ran and managed their operations. It is worth noting that the indigenous nobility often took these management positions for themselves because …they saw it as a good opportunity to exercise their diminished power and even to make some financial gain20.

Trustworthiness

At first, the indigenous people distrusted the hospital centres, as there were no similar institutions in the pre-Hispanic culture. Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta noted resistance and rejection: ...[the Indians] more want a tortilla in their huts, than a good ration in a palace or in a strange house, and more directly he says:

Neither I can, nor can it be done away with the Indians who enter the hospital to be cured, unless it is some poor person who has no one to look after him. The rest want to die in their homes more than they want to be healthy in the hospital21.

For the sick natives, hospitalisation was tantamount to death and the process could even be accelerated because:

…the Indians from the day that they were oteaban considered themselves dismissed from life and from that point they no longer made remedies for life, nor ate a single morsel (Joan de Grijalva, quoted by León-Portilla)22.

We must not only consider the rejection of the hospital structure per se, but also the strangeness and repudiation of European medical theory and practice and of the colonisers themselves, seen as foreign invaders. Still in the 18th century, a priest living in Tlalnepantla (near Mexico City) stated that:

…those who have had experience with the Indians (as I have, who out of my sixty years of age, have handled them thirty-five) will relate how they are opposed to treatment with Spanish medicine, and how they spend their lives convinced that the Spaniards are deceiving them23.

On the contrary, Mendieta himself mentions that a different behaviour is observed in the Michoacán territory where …all [the Indians] from the youngest to the oldest go to be cured and to die in the hospital24, which demonstrates the broad benefits of the Quiroga project where the deep and intense community participation managed to penetrate the Purepecha culture and to lower the obstacles of indigenous insecurity and mistrust.

Evolution, decline and disappearance

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the hospitals maintained their continuity, and even experienced a certain upturn with the arrival of new hospital orders25. The 18th century saw the beginning of a period of crisis that led to the closures that took place during the first half of the 19th century.

We know for certain that the frequency and intensity of the dangerous epidemics had already diminished; that religious conversion was no longer a priority for ecclesiastical leaders; that the civil authorities had already suppressed some monastic orders and were taking over the activities that the Church had assigned itself; and that, politically, the Indians were of secondary interest in the face of the overwhelming emergence of Creole and mestizo social groups in independent Mexico.

Utopias and evangelising goals forgotten, the Church transformed the exemplary community life of the indigenous peoples into free labour, as Viceroy Revillagigedo recounts in his 1790 report:

The work of Don Vasco, the work of the Augustinians, and the Franciscans had been undone. The parish priests had turned the hospitals into institutions of servitude. The Indians and their children were as if enslaved to them.

On the financial front, the independence movement that began in 1810 disrupted the royal allocations given by the dying viceregal government. The various revenues were gradually reduced, and the all-important annual half-real tax paid by the Indians was cancelled first in 1814 and finally in 1822.

Figure 6. Main entrance of the Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales in Mexico City.

The Hospital Real de Naturales experimented with multiple survival strategies such as external indebtedness, increasing revenues, reducing salaries, staff and the number of beds. All to no avail. On 21 February 1822, the most important Indian hospital in America was closed.

The real reason for the closure had to do with the idea of the longed-for equality among all Mexicans and the supposed abolition of racial differences, where the Indians were not to enjoy any privileges or particular perks27. The bill published in Puebla is very clear in this respect: The corresponding order will be given so that the other Hospitals will admit sick Indians, like any other citizen28 (Figure 5).

Socio-cultural adaptations

We will now discuss the concrete strategies implemented by the monastic orders and the civil authorities in the hospital foundations to achieve a better approximation to the needs and demands of the newly conquered indigenous peoples.

We must remember that these apparently charitable and humanitarian actions cannot be decontextualised from a general colonialist policy that sought – more than the mere exercise of armed occupation – hegemony and social and ideological legitimacy through the execution of collective works. In this sense, most of the indigenous hospitals were administered, directed and controlled by Europeans, but in some cases Indian participation was overwhelming, i.e. they adopted the initially imposed institution and made it their own.

Some of the issues that will be described and analysed below are: the exclusivity of the hospital service to indigenous peoples, the adoption of sufficient architectural forms and spaces, the use of native human resources, the amazing community participation, the employment of priests and academic doctors sensitive to the intercultural situation, the use of the knowledge and practices of indigenous doctors, and finally, the use of material and symbolic resources referring to medicinal herbal medicine, temazcals, thermal baths, regional foods and spiritual assistance.

Exclusivity

Except for Indians suffering from leprosy, madness and antoninos,

…All the Indians of New Spain, regardless of their place of origin or residence, had the right to be cured in the Royal Hospital of Naturals, with no other condition than that of being Indians29.

Figura 7. Acceso al patio principal del Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales.

In this sense, although the humanist, charitable and just thinking of the Franciscan missionaries was at work in the founding of hospitals exclusively for the Indians, this division also allowed the evangelising effort to be concentrated on the defeated Indian peoples, thus transferring armed domination to the realm of politics and ideology, but also simultaneously reproducing the rigid social and cultural scheme of caste.

A royal decree signed by the Spanish monarch in April 1701 points out this separation with extreme clarity:

…and because this kind of people, due to their special nature of ailments and bad smell, need to be separated from the Spaniards and other mistos, not being well with each other and contrary to the fact that the Spaniards were being treated with patience, I beg you to order that the aforementioned Hospital de la Charidad del Espiritu Santo of that city not admit Indians in its infirmaries, ordering you, my Viceroy, to go and send all the sick and suffering in the Royal Hospital, which is deputed for them….. . .30.

As far as we know this order was strictly complied with and in the ordinances of the Royal Hospital for Naturals:

… may not the Exmôs. Señores Virreyes, the board of the said Hospital, the administrator of the same, nor any other Minister, nor any other Sugeto, admit to cure in it any Person who is not precisely Indian, in view of the fact that it is solely and specifically established for them31 and it was even argued that with the admission of the sick of Spaniards and other castes the Indians would be defrauded of what is theirs, and because there are other Hospitals to go to…32.

On the other hand, in the hospitals established by Vasco de Quiroga this exclusivity was not so radical in the acceptance or rejection of non-Indian users, since the functions of the hospital went beyond the realm of healing by receiving travellers in transit.

Architecture

Contrary to what might be believed, the buildings destined for Indian hospitals – at least in Mexico City and elsewhere – were of good quality. Civil and ecclesiastical chroniclers describe them in glowing terms. Thus, about the hospital located in Tiripitío (Michoacán), Fray Matias de Escobar refers to … that no one, on seeing its pride and grandeur, would judge it to be a work for poor miserable Indians33 adding that it has large and spacious rooms and offices, large windows and a garden with medicinal, ornamental and edible plants. The same friar points out that the Hospital of Uruapan is …so costly and capable that by itself it is a memorable work34.

Figure 8. Architectural plan of the church belonging to the Royal Hospital of San José de los Naturales.

The selection of a suitable site for the hospital was also very important as it was intended that it should be built on a site as

to be built on as healthy a site as possible. The one in Ocotlán, Jalisco had to be a decent, comfortable and clean place and the building of good walls, well mudded and whitewashed, covered with good wood and at the most well covered with straw35. This also demonstrates the use of local materials.

With regard to the Royal Hospital of San José de los Naturales in Mexico City, Cervantes de Salazar describes it as early as 1554 as … a hospital with very good tents that the Indians have made for sale, where the poor and sick Indians are cured36.

By the 18th century it had two levels (Figure 6). On the ground floor there were the accessories, the apothecary, two chapels, a bell tower, a main courtyard, laundry rooms, a laundry room, a room for anatomical dissections, the cemetery, the storage rooms, the kitchen, the atolería, the porter’s room and the temazcal bath (Figure 7).

On the upper floor there were eight general rooms, some for men and others for women, one for contagious patients, the dining room, the laundry, the storeroom for the pantry, special rooms for nurses, doctors and practitioners, chaplains, the administrator and the normal bathrooms. When there was overcrowding due to epidemics, the corridors were used.

According to J. Muriel … the intention was to give the Indians the best hospital service37 and we add that the spaces were subordinated to the needs of the sick, including, as we will detail later, the temazcal and other rooms where tortillas and atole, indigenous foods par excellence, were prepared (Figure 8).

Native personnel and community participation

In the hospitals founded by Vasco de Quiroga there was an extraordinary collective organisation that fully involved the indigenous communities. In the Reglas y Ordenanzas para el gobierno de los Hospitales de Santa Fe de México y Michoacán the collective work is indicated to obtain communal and family benefit for the participating Indians through the equal distribution of goods according to criteria of need and quality38 since the aim is that you live without need and [with] security and without idleness and out of danger and infamy of it…39 (Figure 9).

In addition to general recommendations on the usufruct of orchards, teaching agricultural and trade skills to children, ideal ages for marriage, family breeding of domestic animals, horticultural care and other activities, reference is made to the number of families who should participate in hospital activities, their working attire, election of authorities, repair and maintenance of the building, settlement of complaints and lawsuits, the review of land intended for hospital service, and the need for bodily and spiritual cleanliness40.

Figure 9. Reglamento de los pueblos-hospitales created by Bishop Vasco de Quiroga.

Working in the hospital meant a voluntary effort that freed the Indians from personal service to the Spanish encomenderos and exempted them from tribute in general. The volunteer couples called semaneros (because they worked a full week) had to lead an almost monastic life, where sexuality was suspended, and hospital activities were concentrated on the careful care of the sick and pilgrims, the preparation of food, washing clothes, cleaning and making beds.

The presence of the Indian weekwatchers was vital, as the sick had great confidence in them.

Thus Muriel relates that:

The natives went to them without fear and with the same confidence with which they attended school or the workshop (…). In the other hospitals the sick were segregated from society, in the infirmaries of Santa Fe they were more closely united with it, which took them under its protection, which gave them the best it had in food, clothing, etc. and even more, taking turns to visit them and attend to them personally. All the inhabitants of the village knew that at some time or other they would go to the infirmary, either as sick or as their nurse.

In the day-to-day organisation of the hospital, the friars were in charge, but the Indians themselves elected the hospital authorities, with the prioste or prelate being selected from among the oldest Indians.

Another organisational form that was directly linked to the hospital were the cofradías, or groups of Indians dedicated to fostering religious life within the hospital. They had their own property and celebrated the patron saint’s feasts with great splendour. In the Ordenanzas of Fray Alonso de Molina, the confraternities had the following functions:

… … to wash the sick, apply medicine, attend to all their needs, feed them and give them food, call the priests to give them the last sacraments, call the notary in the case of the sick person having wealth, to have a will made, to help the sick to die well without abandoning them for a moment during their agony, and to warn all the confreres by ringing a bell when death occurred, so that prayers could be said immediately for the deceased42.

The dedication and commitment of the semaneros and the cofrades astonished the Spaniards. Fray Toribio de Motolinía in his Historia de los indios de Nueva España reports that:

The Indians have made many hospitals where they cure the sick and poor, and from their poverty they provide them abundantly, and as they know how to serve so well, that it seems they were born for it, they lack nothing …43.

Although the hospital was a European technological concept, the Indians showed a great affinity for this form of collective care for illness. This is why we can understand the enormous number of hospital buildings that were founded all over New Spain in the 16th century, since every town had its own hospital or wanted one, either on the initiative of the missionaries and civil authorities, or at the express request of the Indian towns. In all cases, indigenous participation was always sought. In 1580 the bishop of Michoacán, Fray Juan de Medina Rincón said that:

There is hardly a town with twenty or thirty houses that does not have its hospital and is proud of it (…) The way to support them is that all the men and women go to serve, so many Indians according to the need of the hospital, and they all do their alms and work for the hospital44.

It should not be forgotten that apart from a few Spanish authorities, all the hospital staff were natives and this – in a way – guaranteed the influx of poor and sick Indians as they belonged to the same social group, also suffered the calamities following the conquest and shared with them their language, worldview and illnesses.

Trained academic doctors

Since the sick in the hospitals were indigenous people who had little or no command of Spanish, the friars were obliged to know and express themselves in the local languages. In the case of the Hospital Real de Naturales, the rector and the chaplains had to be fluent in Náhuatl and Otomí (or ñañú) because the patients were from the central highlands of Mexico, the Sierra de Puebla, the valley of Morelos and the Balsas Basin. Obviously, the evangelisation and religious conversion of the Indians were fundamental and a priority for the spiritual salvation of the Indians and the physical survival of the colonial regime.

In the case of doctors, complete mastery of the native languages was not required. In the Constituciones y Ordenanzas para el regimen, y govierno del Hospital Real y general de los Indios de esta Nueva España (1778), the criteria requested was that they should be:

… always of the most skilful, and of the greatest acceptance in it, active, and of long experience, knowledge of the country, consequently of the natures and complexions of the Indians, their way of life, the food and drink they use, the illnesses that are usually proper to their native natures and complexions, since all this can lead to success in curing their ailments, especially the epidemics to which they are prone45.

As can be seen, the requirement did not go so far as to require them to speak Nahuatl or Nañú, but he was supposed to have a minimum of information about the local cultures (Figure 10).

Acceptable indigenous doctors

One of the fundamental developments of the sixteenth century in Novo-Hispanic healing practice was the full and open participation of indigenous physicians in Indian hospitals. In the ordinances of Fray Alonso de Molina, translated from Latin by Miguel León-Portilla, it is stated that:

And it is necessary that the true shamans be asked, those who experimentally know the herbs, not the tricksters, those who look [divinate] in the water, those who are servants of the devil. But a very great service of the confreres will be that they make the medical titici enter the hospital, but let those enter who are tlamatinime, true sages, those who know experimentally the herbs, of what condition the various diseases are. Only these there will live [in the hospital] those who are true sages, those who know by experience the herbs, so it will be healing […]46.

Molina’s insistence is more than notorious, the entrance is only for the indigenous doctors who know the medicinal plants, that is to say, the yerbateros. The others, the witchdoctors, are openly excluded. Another specialist who will have access will be the temazcalero, but surely dispossessed of his identity and link with the goddess of the temazcales. In the mid-18th century temazcals were so frequent in Mexico that the Ordinances of the Royal Hospital for Naturals state … that there is no village, however unhappy it may be, where there are none, and many of those who can keep them in their own houses47. As for their usefulness, Fray Matías de Escobar relates that the curative benefits are widely esteemed and praised by his fellow religious48.

Finally, midwives from outside the hospital attended to pregnant women, although the documentation does not provide us with any further details.

According to J. Muriel, the ordinances also established that the indigenous doctors should transmit their knowledge to other Indians, which would mean that it was not enough to apply herbal remedies alone, but that the reproduction of traditional knowledge was also present49.

Medicinal herbalism

Again, in his Ordenanzas, Alonso de Molina points out that

It is required that the confreres first of all confer, that they seek all kinds of remedies, the zacalpatli, grass [or common] remedy or any other valuable one, because it is so written in the divine word [the Sacred Scriptures], any herb, grass or any other, is applied by virtue of the Lord our God50.

In this sense, New Spain’s hospitals would begin to test the salutary properties of some plants, and there would even be a mutual interrelation between indigenous doctors and academics in terms of herbal products, which would increase notably when Dr Francisco Hernández established his residence in the Royal Hospital of Naturals, where he would experiment clinically with the herbs collected on his travels through some of the territories of New Spain. Doctor Alonso López de Hinojosos -who worked at the Hospital- is a witness (and possible actor) of this experimentation by Francisco Hernández in the 16th century. Thermal baths

It is interesting to note that in addition to the temazcal baths, some patients were taken to the thermal baths located at the foot of the Peñón, to the east of the city, and had to be transported by canoe. The Hospital had a fixed room that was rented on a continuous basis.

Regional food

The food at the Royal Hospital – according to the regulations of Fray Alonso de Molina in the 16th century – was to be that which the sick desired, that is to say, that to which they were accustomed.

In the 18th century ordinances we find an evident concern for offering adequate food. In 1734, the administrator Agustín de Vidarte stated that the dietary regime was to be shaped according to the indications of the doctors and surgeons, the type of illness and the characteristics of the Indians themselves:

… because it is recognised that the nature of the Yndios is preserved, and is better with the proper drink of atole, and tortillas, that one and the other are made of corn, the usual fruit and seed of this land, and with which they are connaturalised51.

Thus it is known that the hospital had women cooks, others dedicated to the preparation of atoles and others to the making of tortillas, and there was even a special room in the Royal Hospital called the tortilla office52.

The chaplains, the butler and the practitioners were in charge of the distribution and consumption of food. The introduction of foreign food was forbidden, and the porter: …will be very careful that those who come in to see the sick do not bring them food or drink, much less [the] white pulque53.

Spiritual care

All the hospitals in New Spain had a regular religious service which allowed for the continuity of the evangelising goal and the satisfaction of the spiritual needs of the hospitalised sick, which is why the presence of altars and the celebration of masses in the hospitals were as essential as medical care and the provision of medicines54.

Figure 10. Regulation of 1776 for the better functioning of the Royal Hospital of San José de los Naturales.

In the Hospital Real de Naturales, the ordinances obliged the chaplains on duty to immediately assist the newly admitted patient in order to instruct him and catechise him, ensuring that in this hospital he was not only provided with an abundance of corporal medicine, but also with spiritual medicine55.

Each infirmary room had its own altar (to Saint Xavier in the women’s ward, and to Saint Michael in the men’s), where the chaplains administered the sacraments, led the daily prayers and taught catechism.

Among the ordinances of Vasco de Quiroga it was indicated that: … on weekday mornings do not miss mass if possible56, and mass was even celebrated in the middle of the courtyard so that all the sick could hear the mass.

Epilogue

The importance that the Catholic missionaries gave to the evangelisation of the newly conquered Indian villages is unquestionable. One of the best strategies was the establishment of hospitals whose mission was twofold and simultaneous: on the one hand, to alleviate the suffering of the sick and, on the other hand, to bring about an ideological change in favour of Christianity.

The description and analysis of the daily life of the New Spanish hospitals founded by the monks Pedro de Gante, Alonso de Molina, Juan de San Miguel, Vasco de Quiroga and others shows that it is possible to find a balance between modernity and tradition, biomedicine and popular medicine, drugs and medicinal plants.

Today there are hospitals for indigenous people in Mexico where they offer industrialised boxed bread instead of tortillas, bottled soft drinks instead of pozol or chicha de maíz, where they speak to them in Spanish and not in their native language, where they use only beds and not a few hammocks, only academic medicine, disregarding the human, material and symbolic resources of indigenous medicines.

There is a need for changes that respond to the cultural particularities of indigenous peoples.

Appropriate intercultural medicine must be practised, where modern and up-to-date medical technology coexists with native socio-cultural expressions. It is to create an integral hospital space for quality care for indigenous patients57.

It requires a multidisciplinary organisation and infrastructure that favours the application and adaptation of services to local indigenous cultures.

The objective is to achieve cultural identification between the hospital and the indigenous people(s) through the use of rural schedules, preferential use of the indigenous language, preparation of regional food, positive interaction between academic doctors and traditional therapists, recognition of medicinal herbal medicine, obligatory intercultural training for social service interns and doctors working in indigenous regions, and the development of health programmes that take into account community values and norms, among other aspects.

Why were we interested in this historical enquiry? Simply because the founders of these hospitals used common sense to make significant modifications so that these spaces would be accepted and appropriated by the conquered Indians. Now, this common sense can also serve us, but medical anthropology can provide an updated evaluation with better methodological instruments that will lead us to achieve more coherent and systematised modifications that will result in the proper functioning of institutional and private hospitals, and above all, in obtaining the desired quality of services through the satisfaction of the hospitalised indigenous patient.

We can conclude that the lessons of the past – which enable us to avoid the mistakes of the present – are to be found in the history of medicine. This history will serve to build the present and guide the future. Thus there will be an alliance between history and medical anthropology. The uses of history and anthropology in the service of the most needy men, women and children of our Hispanic American countries, of our Indians.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021