Source:La Razón

They have been used for bullfighting spectacles, as barracks and prisons, for music concerts and to sponsor political movements

The world of bullfighting is not for everyone. It is well known the confrontation that has existed between anti-bullfighting and bullfighting for decades, and the campaigns that certain political groups have launched to eliminate one of our best known traditions at an international level. Talking about bullrings can, therefore, be somewhat delicate. But let’s forget about bullfighting for a second. Let’s erase all ideologies. Let’s empty the bullrings full to overflowing with enthusiasts with the brave little bull panting with thick, shiny blood running down its back. Let’s imagine that we are not excited primates and forget the good or bad of bullfighting, the ideologies, let’s definitely become human beings with the potential to reach a fourth dimension. Bullrings are much more than killing centres, as some say. They are buildings. And as buildings they not only have multiple uses (what self-respecting Spaniard has never been to a concert in a bullring?) but they are also owners of a particular and admirable beauty that is worth visiting.

Today we can take the carcass of our popular festival and we can applaud it as we do the Reichstag in Berlin (despite the fact that Hitler organised the worst massacres inside it) or the Invalides in Paris (even though a man who caused the death of millions of Europeans is buried there), simply for what it is, a carcass. Independent of humanoid vices. Here are the five most emblematic squares in Spain (although there will be some more).

Las Ventas bullring

Built in a neo-Mudejar style thanks to the designs of the architect José Espelius, this is one of the architectural symbols of our capital. And it may seem curious, but it was inaugurated twice: the first time in 1931, although it was quickly closed again because its accesses were not yet finished; the second time was in 1934, and then definitively. It seems paradoxical that the instigators of a third republic want to demolish what they built in the second republic, but we said we would not talk about politics and that is what we are going to do. It seems paradoxical, that’s all. It has a capacity for 23,798 spectators. Its ring measures 61.5 metres in diameter, the second largest in the world, and the width of the alley is 2.2 metres. Although occasional bullfights are held inside the bullring, mainly during the San Isidro festival in May, it is also common for concerts and other events aimed at the public to be held inside. It was even used by Francisco Franco in 1939 as a provisional prison camp.

Ronda Bullring

The historical importance of bullrings finds its ideal representative in Ronda. It was inaugurated on 19 May 1785, exactly 300 years after the reconquest of the town by the Catholic Monarchs, and is not only one of the oldest bullrings in Spain, but its 66-metre diameter ring is considered to be the widest in the world, including Mexico. Dozens of ghosts haunt this square and a hundred legends swarm around it. It was used as a barracks by Napoleon’s despicable troops, who, as was usual for them, left the square in ruins before fleeing back to France, forcing it to be restored. It also served for a few months as a camp for Republican prisoners. And of all the bullfights that have been held here (I imagine we could fill the bullring to overflowing with all the blood that has been spilt in the ring) only one ended with a fatal goring. Legend has it that Francisco Herrera, known as “Curro Guillén”, was gored here in 1820 and buried next to the bullring chiqueros (paddocks for the bulls). During restoration work carried out on the bullring decades later, his remains were found where the legend said they would be.

Bullring of La Maestranza

Seville: castanets, tablaos, red sequined colours, manzanilla, olé, olé, wine, bullfighting, olé, the Giralda, olé, Seville is the standard-bearer of the Spanish brand all over the world. No city better expresses the cultural clichés that foreigners have about us. So it seems only natural that its bullring is one of the most emblematic in our country. Among bullfighters it is known for the respectful silence that prevails during its bullfights, as if the spectators were parishioners who listen, bow their heads, move their lips while the priest with the cape recites the prayer. It is known among tourists for the beautiful image it leaves in the city. Its whitewashed walls and white paint underlined with a pastel yellow colour, its baroque style contrasts sharply with the style of the Madrid square, giving us a glimpse of the architectural versatility of these buildings that resemble the open mouth of a city. Inside you can visit the Bullfighting Museum (excellent for learning, for better or worse, about this ancient spectacle) and the chapel of the Bullfighters, coloured in gold and illuminated.

Seville: castanets, tablaos, red sequined colours, manzanilla, olé, olé, wine, bullfighting, olé, the Giralda, olé, Seville is the standard-bearer of the Spanish brand all over the world. No city better expresses the cultural clichés that foreigners have about us. So it seems only natural that its bullring is one of the most emblematic in our country. Among bullfighters it is known for the respectful silence that prevails during its bullfights, as if the spectators were parishioners who listen, bow their heads, move their lips while the priest with the cape recites the prayer. It is known among tourists for the beautiful image it leaves in the city. Its whitewashed walls and white paint underlined with a pastel yellow colour, its baroque style contrasts sharply with the style of the Madrid square, giving us a glimpse of the architectural versatility of these buildings that resemble the open mouth of a city. Inside you can visit the Bullfighting Museum (excellent for learning, for better or worse, about this ancient spectacle) and the chapel of the Bullfighters, coloured in gold and illuminated.

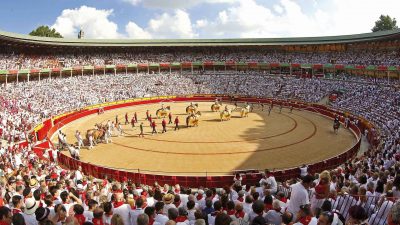

Monumental Bullring of Pamplona

The Sanfermines do not end until the last bull of the afternoon expires. One of the most internationally recognised bullfighting traditions has its beating and vigorous heart in the bullring of Pamplona. Where the bullfights of Seville are silent and almost seem to be done by stealth, in Pamplona there is a shouting match seasoned with calimochos (alcoholic drink made with equal parts of wine and cola), sandwiches, shouts, enthusiasm, bustle, serpentines. Built in 1920 and with a capacity for 19,529 spectators, it is the exact place where the San Fermín runs end, as if the streets of Pamplona were veins, the characters dressed in their scarves their red blood cells and the bullring their heart pumping blood. Sticking to a purely aesthetic judgement, we cannot say that it is as beautiful as other bullrings in our country. The beauty in this case contains more abstract dyes, the beauty is in a tradition, in those screams, in the drunks. It is a beauty that can be heard and smelt but that can hardly be seen, if you don’t have your eyes ready for it. And the stories surrounding this building are not few. For example, there is one that tells that in 1898 the bullfight on the 10th of July and its bull run were cancelled. It turned out that the bulls had escaped when they were being transferred from the Sario to the corral in the Rochapea. The last bull was not found until 14th October. It was grazing peacefully on Usquía mountain, near Lizarbe.

The Sanfermines do not end until the last bull of the afternoon expires. One of the most internationally recognised bullfighting traditions has its beating and vigorous heart in the bullring of Pamplona. Where the bullfights of Seville are silent and almost seem to be done by stealth, in Pamplona there is a shouting match seasoned with calimochos (alcoholic drink made with equal parts of wine and cola), sandwiches, shouts, enthusiasm, bustle, serpentines. Built in 1920 and with a capacity for 19,529 spectators, it is the exact place where the San Fermín runs end, as if the streets of Pamplona were veins, the characters dressed in their scarves their red blood cells and the bullring their heart pumping blood. Sticking to a purely aesthetic judgement, we cannot say that it is as beautiful as other bullrings in our country. The beauty in this case contains more abstract dyes, the beauty is in a tradition, in those screams, in the drunks. It is a beauty that can be heard and smelt but that can hardly be seen, if you don’t have your eyes ready for it. And the stories surrounding this building are not few. For example, there is one that tells that in 1898 the bullfight on the 10th of July and its bull run were cancelled. It turned out that the bulls had escaped when they were being transferred from the Sario to the corral in the Rochapea. The last bull was not found until 14th October. It was grazing peacefully on Usquía mountain, near Lizarbe.

Béjar Bullring

They say that the bullfighting tradition in Spain goes back to the time of Asterix and Obelix but the rain and wind have taken away the oldest bullrings, unless we consider the old Roman amphitheatres and their wild beasts as the primitive spectacle that later became bullfighting. So the oldest bullring still standing in Spain is in Béjar and was inaugurated in 1711. It is known as La Ancianita. Built with brick and lacking the frills and decorations that make up previous bullrings, representing an almost professional sobriety, the bullring seems to open its eyes to tell us in a deep voice: “things happen in here”. And then it closes its eyes again and doesn’t speak to anyone for another two hundred years. But no, he thinks better of it, he opens them again to tell us something else: “since my inauguration, bullfights have been banned more than a few times: during the reigns of Fernando VII, Carlos III and carlos IV, if we are precise. This bullfighting and anti-bullfighting business is as old as Alfonso X, although some smart alecs play the progressive game. And I don’t mind if now they ban and then they don’t, as long as some imbecile doesn’t come and knock me down to express a political message.” Because this ring thinks that bullfighting is a matter of each individual, changing with history, but that to demolish historical buildings without rhyme or reason (as it is rumoured that they intend to do in Barcelona) is a bit of a brute.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1648 Pedro II of Portugal is born.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021