Source:Libertad Digital

The order was allegedly given by Alexander Orlov, head of the NKVD, the Russian espionage, who was also involved in the kidnapping and assassination of Andreu Nin, leader of the POUM, on Stalin’s orders.

On 8 December 1936, while flying over the town of Pastrana in Alcarria at an altitude of 3,000 metres, a twin-engine Potez-54 belonging to the French Embassy in Madrid, which had taken off from Barajas at 12.20 p.m. with two crew members and five passengers, was strafed by a fighter plane.

As a result of the strafing, which caused gunshot wounds to three of the five passengers, the French aircraft had to make a forced landing in a field four kilometres from Pastrana. Due to the impact, the plane capsized and then overturned.

Among the wounded was Georges Henny, a Swiss doctor who had been the delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Spain since 11 September 1936. Together with Felix Schlayer, the Norwegian consul, he had seen at first hand the massacres in the prisons of Madrid and the massacres at Paracuellos and Torrejón de Ardoz in November and December 1936. According to the Red Cross archives in Geneva, Henny had reported in November the departure of nearly a thousand prisoners from the Modelo , San Antón and Ventas prisons, of whom he noted that only 196 had arrived in Alcalá.

As a result of the strafing of the Potez-54, Henny was shot in the right calf. Schlayer claimed that Henny was carrying documentation on the killings in Madrid to report on them in Geneva.

At that time, the Council of the League of Nations was to meet in the Swiss city, which the Republican government had requested to convene, and where the Republican Minister of State, Julio Álvarez del Vayo, was to speak against the military intervention of Germany and Italy in the Spanish conflict. Henny’s documentation would have called into question the intended effect of Álvarez del Vayo’s denunciation.

French journalist Louis Delaprée, correspondent of “Paris-Soir”, was also wounded in the downing of the plane, hit in the groin and belly by bullets from the attacking plane. As a result of these wounds, Delaprée died three days later in the San Luis de los Franceses hospital in Calle Claudio Coello, 32, Madrid. He was 34 years old and left behind a widow and four children.

Georges Henny, delegate of the International Red Cross, recovers from his injuries in a Madrid hospital after the plane was shot down | Ministry of Culture

Delaprée had strongly denounced in his chronicles from Madrid the massacres of civilians as a result of the bombardment by Franco’s artillery and air force. He was on his way back to France at the end of his reporting mission in Spain and after a disagreement with the editors of his newspaper, whom he accused of giving less importance to the murder of a hundred children than to “a sigh from Mrs Simpson, the king’s whore”, in reference to the mistress of the British monarch Edward VII. In 2013 his book Morir en Madrid was published, which brings together his chronicles from the Spanish capital, edited by the Hispanist Martin Minchom.

Another journalist, André Château, a correspondent for the Havas agency, was also hit by machine gun fire. He was wounded in the leg by a shell from the attacking plane, which fractured his tibia and fibula. Doctors eventually had to amputate the limb.

Two Spanish girls were also on the plane: María Carlota and María Dolores Cabello y Sánchez-Pleités. In various sources they appear as “Pleytas” or “Cabello”, but their true identity was unknown until today. My research has finally identified them as the daughters of the marriage between the architect Pedro Cabello Maíz and María Carlota Sánchez-Pleités y Jiménez, Marquise de Los Soidos y de Fromistá, Grandee of Spain. Little María Dolores suffered a broken forearm when the plane landed. Before taking off from Barajas, Louis Delaprée kindly offered to exchange seats with María Dolores so that she would be more comfortable on the journey. That decision cost the journalist his life and probably saved her life.

Pilot Charles Boyer and radio operator Bougrat were the crew of the French Embassy plane. Their skill prevented further damage by landing in a farm field four kilometres from Pastrana (Guadalajara), on the right-hand side of the road leading from Pastrana to Fuentelaencina. An examination of the landing site reinforces the idea that the plane overturned and was left upside down due to the unevenness between the boundaries separating the fields.

The injured were attended to by Francisco Cortijo Ayuso, a doctor from Pastrana quoted by Camilo José Cela in his Viaje a la Alcarria, who rushed to the scene of the accident. His testimony was reported in the Revista de Historia Militar of March 2001 by Felipe Exquerro Ezquerro, one of the great specialists in the history of aeronautics in Spain. Dr. Cortijo stated that he saw the plane’s passengers burn a leather briefcase and photographs in a bonfire. He also affirmed that, before the arrival of several cars with authorities from Madrid and Guadalajara, Dr. Henny entrusted him with two bags of the diplomatic pouch which he was later able to hand over to the Secretary of the French Embassy.

The newspaper “Paris-soir” reports on 10 December 1936 that its correspondent in Spain, Louis Delaprée, was wounded in the attack. He died a day later.

The event immediately provoked a reaction from the press in the Republican zone, which did not hesitate to blame the attack on the civilian plane on the “Fascist air force”. The Madrid daily “La Voz” went so far as to headline on 9 December: “Germany fires again on French planes”. However, doubts about this version soon began to be raised.

The unknowns

In the first days of January 1937, several French newspapers echoed an unofficial report published on 31 December, according to which the French government had confirmed, after an investigation, that the attack had been carried out by Republican aircraft.

In his book Paracuellos, cómo fue, republished in 2005, the hispanist Ian Gibson writes that

…it appears that the French government carried out an investigation into the incident in the skies above Pastrana. If such a report is ever published, it may shed light on an episode that has so far been shrouded in mystery.

The report exists and is kept in the archives of French diplomacy in Nantes. The hispanist Martin Minchom consulted it years ago and used it to document his article El ‘Guernica’ de Picasso y “la prensa que miente, la prensa que mata”, published in 2012.

The Potez-54 plane belonging to the French Embassy in Madrid, shot down in Pastrana (Guadalajara) on 8 December 1936.

The report confirmed that the attack on the Potez-54 of the French Embassy in Madrid had been carried out by two fighters with the distinctive red stripes of the Republican air force: a monoplane that identified the French aircraft and a biplane that, after that identification, strafed it.

In the light of this conclusion, Minchom places the leaking of the report’s conclusions to the press in the context of the confrontation in France between supporters and opponents of the Spanish Republic. This confrontation had been exacerbated by the death, as a result of the attack, of Louis Delaprée, correspondent of Paris-Soir, one of the staunchest denouncers of the brutal effects of Franco’s bombings on the civilian population of Madrid.

The left-wing media campaign was, however, countered by Delaprée’s widow, Camille, who sent a telegram to L’Humanité, the Communist Party’s newspaper, assuring them that “they have no right to use the name of the man I loved so much for political purposes” and that her husband “hated only one thing: war”.

The leaking of the report, according to Minchom, was a trick played by the Quai d’Orsay in the midst of the controversy, given its “ambivalent attitude” towards the Republican side. This ambivalence, which for other authors was open hostility, marked the position of French diplomacy under the popular-front government of Léon Blum, fearing that it would lose the support of Britain and leave France isolated if it had intervened directly in favour of Madrid.

There is one important element, however, that Minchom may have overlooked in this matter. Once the report had been completed, the French government confined itself to sending the Republican authorities a formal note of protest, but without giving it any publicity, demanding that they punish the perpetrators of the attack and compensate the victims. But Largo Caballero‘s government, far from taking the matter lying down, continued to blame the attack on Franco’s air force.

The Minister of State, Julio Álvarez del Vayo, did so on 3 January 1937, five days after receiving the protest note, in response to leaks in the French press that blamed the attack on Republican aircraft.

According to the note from the Fabra agency published by La Vanguardia on 5 January,

… in a letter officially addressed by Álvarez del Vayo to the French Chargé d’Affaires in Valencia, the Spanish Minister of State states categorically that the legal government has incontestable proof that the plane in which the journalist Delaprée was travelling was attacked by a rebel aircraft and not by a government plane, as certain reports in the right-wing French press have tried to make people believe.

On the same day that the incident took place – Alvarez del Vayo’s letter pointed out – and a few hours after it, the airfield at Alcalá de Henares was attacked by rebel planes, bombing and fighter planes, which undoubtedly included the attacker of the French Embassy plane. An hour earlier, the rebel planes had made a reconnaissance flight in the area around Pastrana.

The Fabra agency’s dispatch reported that

the Spanish government ends by advising the French government to help carry out a survey to refute the fantastic information published by the fascist newspaper L’Echo of Paris, according to which the government wanted to shoot down the plane of the French Embassy because Hery (sic), delegate of the International Red Cross in Madrid, was travelling on it.

Fabra’s note ended in a truly fantastic way, assuring that, according to Álvarez del Vayo, “Hery (sic) was assassinated a few days ago by 1,500 soldiers of the Tercio (sic) under the orders of the rebel generals”. The fact is that Georges Henny, a delegate of the International Red Cross, who unequivocally claimed to have been the target of the attack on the French Potez-54, left Republican Spain shortly after the incident, never to return.

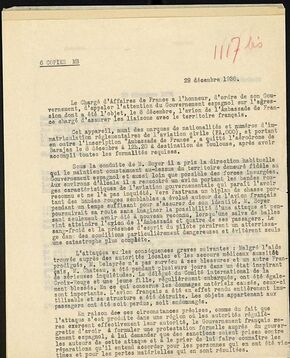

Note of protest from the French government to the Spanish Republican authorities, denouncing the shooting down of the plane by government fighters.

It was in response to these statements by Álvarez del Vayo that the Quai d’Orsay finally decided, ten days after writing it, to publish in the press the note of protest it had sent to the Republican government. It is possible that the leak of the conclusions of the official investigation, pointing to the authorship of Republican planes, could have been the work of right-wing elements in the French Foreign Department, as Minchom insinuates. But what is clear is that Blum’s government had until then preferred not to make public its note of protest to the Madrid authorities so as not to damage the cause of the Spanish Republic.

The French government’s protest note, which we reproduce in full, makes the identity of the attacking aircraft very clear:

29 December 1936

The Chargé d’Affaires of France has the honour, by order of his Government, to draw the attention of the Spanish Government to the aggression to which the French Embassy aircraft in charge of securing connections with French territory was subjected on 8 December.

This aircraft, bearing the nationality markings and registration numbers required for civil aviation (FA.000), and also bearing the inscription “French Embassy”, left Barajas aerodrome at 12.20 p.m. on 8 December for Toulouse, after completing all the required formalities.

Piloted by Mr. Boyer, it took the usual course that keeps it constantly over territory that has remained loyal to the Spanish government and as far away as possible from the insurgent forces. In the vicinity of Alcala he came across an aircraft bearing the red bands characteristic of government aviation, which seemed to have recognised him, so he did not worry. Towards Pastrana, a fighter biplane with similar red stripes hovered around the French plane long enough to be sure of its identity. Mr Boyer continued on his way, not imagining the possibility of an attack and thinking only that he had been recognised again, when a volley of bullets hit the Embassy plane and four of its passengers. The pilot’s coolness and presence of mind allowed a landing under particularly dangerous conditions and prevented an even greater catastrophe.

The attack had the following serious consequences: despite help from the local authorities and immediate medical aid, Mr. Delaprée did not survive his injuries, and another Frenchman, Mr. Chateau, was in a very worrying condition for several days. The delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross and a young woman, who were on board, were also injured. The material damage caused was considerable. The French plane was completely disabled and its structure destroyed. Objects belonging to the passengers were either lost or damaged.

In these circumstances, as well as the fact that the attack took place in a region where the government authorities actually exercise their authority, the French Government regrets to have to make a formal protest to the Spanish Government, to ask it to punish the perpetrators of this attack and to ask it to inform it of the reparations it intends to grant for the victims and for the material losses resulting from it.

Despite the clear identification of the attacking aircraft by the pilot Charles Boyer, Minchom maintains that the French government had “reasonable suspicions, but little firm evidence” to attribute the attack to the Republican air force, and bets that “the French Embassy plane was attacked by mistake, perhaps by Francoist planes, perhaps by Republican planes”. In other words, he goes back to square one.

The French government’s note of protest does, however, leave one strong piece of evidence: that of the testimony of a pilot flying over a nation involved in a civil war and who is assumed to have sufficient knowledge to identify without any doubt the markings of the contending aircraft. The note also confirms that the Potez-54 was the same aircraft that had been flying between Madrid and Toulouse without any mishap until then, which refutes the hypothesis that it was not sufficiently identified, even though it was a bomber converted for civilian flights.

The journalist André Château, who lost his leg as a result of injuries sustained in the attack, considered the International Red Cross delegate to be an “uncomfortable witness”. The French consul in Madrid, Emmanuel Neuville, also had no doubts about this. But most importantly, Henny himself was certain that the attack had been aimed at eliminating him, indicating his absolute conviction that he was the perpetrator.

Over the years, the then head of the Republic’s fighter aviation, Andrés García Lacalle, identified Gheorghij Zakharov and Nicolai Shmelkov in his memoirs, Mitos y verdades, as the Russian pilots who had been involved in identifying and shooting down the Potez-54. According to the British journalist Sefton Delmer, a correspondent during the Spanish war in the 1960s, the order to shoot down the plane was allegedly given by Alexander Orlov, head of the NKVD, the Russian intelligence service in Madrid, who was also involved in the kidnapping and assassination of Andreu Nin, leader of the POUM, on Stalin’s orders.

The attempt to eliminate an inconvenient witness to the Paracuellos and Torrejón massacres, none other than the delegate of the International Red Cross in the Republican zone, proved unsuccessful. But even if the assassination of Georges Henny had been carried out, nothing would have prevented the greatest massacre of civilians of the Civil War, perpetrated under the instructions and with the collaboration of some of the authorities in besieged Madrid and the consent of the others.

(Excerpt from the book Eso no estaba en mi libro de la Guerra Civil, Editorial Almuzara).

Share this article

On This Day

- 1572 Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva founded the town of Guaduas (Colombia).

- 1578 Brunei becomes a vassal state of Spain.

- 1672 Spanish comic actor Cosme Pérez ("Juan Rana") dies.

- 1693 Painter Claudio Coello dies.

- 1702 The Marquis de la Ensenada was born.

- 1741 Spanish troops break the siege of castle San Felipe in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia).

- 1844 The Royal Order of Access to Historical Archives was promulgated.

- 1898 President Mckinley signed the Joint Resolution, an ultimatum to Spain, which would lead to the Spanish–American War.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021