Source:A orillas del Potomac

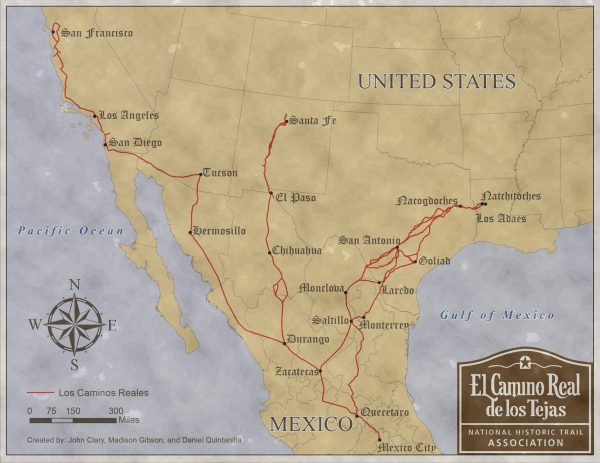

The Spanish colonisers drew “the points” in a vast territory on which colonisation was based: they built missions, presidios (that is, forts), planned cities and created toponymy. Roads (the 5 Caminos Reales), tens of thousands of kilometres long, were laid out to connect settlements and population centres over a large part of the western territory of what is now the United States from the late 16th to the 18th century. Therefore, this civilising work took place centuries before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in the 19th century, who found a fairly structured and well-communicated territory. The Spanish constructions in the USA facilitated the later Anglo-Saxon colonisation, although they hardly ever acknowledge it … You are welcome! These Spanish constructions covered very extensive territories, although not in a dense way.

The reason for this article

On the occasion of my visit to the recent exhibition at the former Spanish Ambassadors’ Residence on L Street in Washington DC, “Designing America: Spain’s Imprint in the U.S.”, organised by the Spanish Embassy, I thought it would be interesting to prepare a commentary on the exhibition.

The exhibition developed the relevant contribution of Spain in the construction of the United States.

Thus, it is emphasised that Spain’s greatest legacy is its imprint on the territory: in the establishment of cities, presidios or forts and missions; the influence on popular architecture and urban planning. Let’s see:

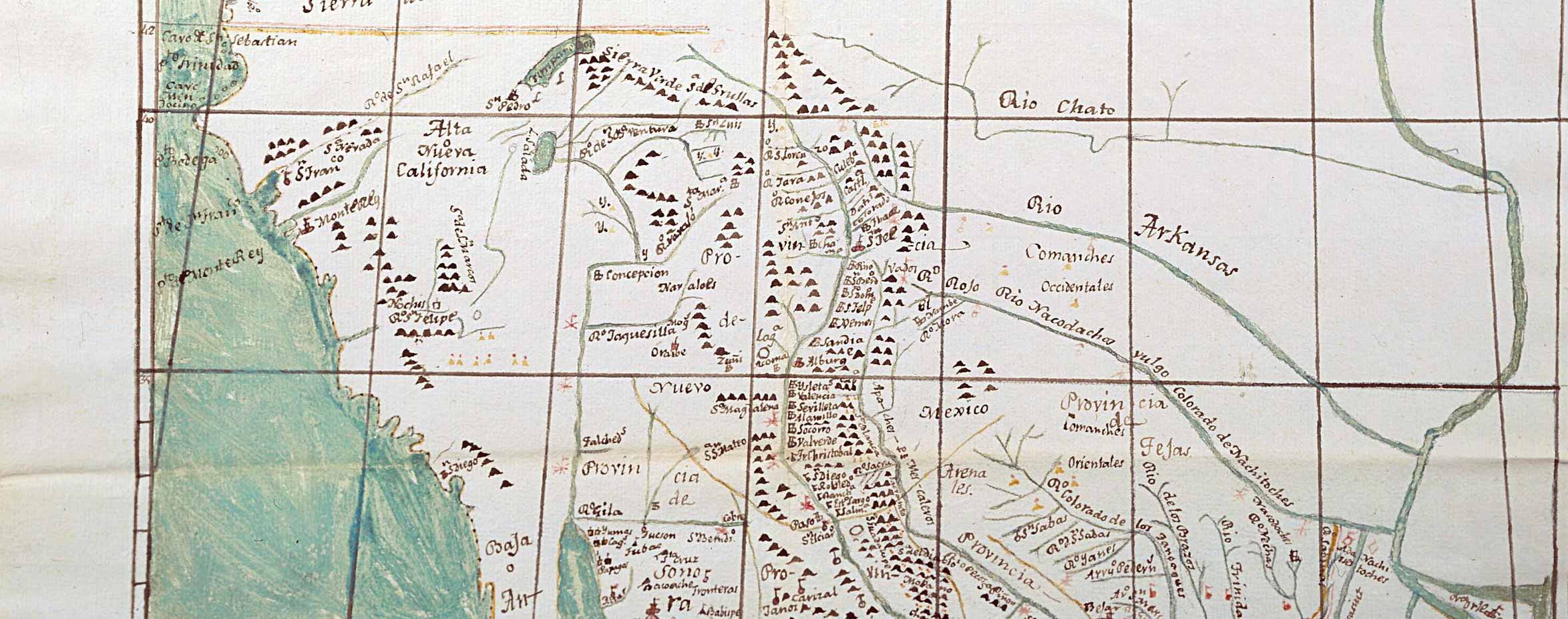

- A large part of the territory of what is now the United States was put on the map by Spanish expeditions: the American landscape and space were mapped thanks to the many voyages of exploration and scientific expeditions that advanced knowledge of nautical charts, geography, botany, etc.

- The new cities of St. Augustine and Santa Fe began to lay out the territorial structure in Florida and New Mexico respectively and promoted the development of hydraulic infrastructures that facilitated colonisation.

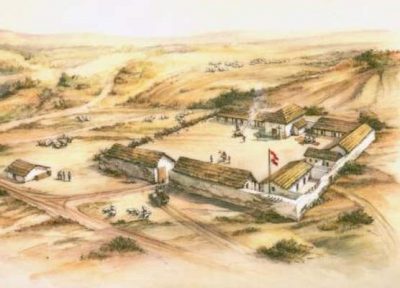

- For their part, the military forts – known at the time as presidios – are a unique example of frontier defensive architecture from the Gulf of Mexico coast to Arizona.

- The network of Franciscan missions along the Pacific coast opened up new trade routes, and the future 21 missions would be the nucleus of many of the most important cities in what is now the state of California.

- Roads (the 5 Caminos Reales) were laid out to link settlements and population centres.

- The first European settlements in the interior of the USA at St. Helena (St. Helena Island, South Carolina) and Fort San Juan (Joara City, North Carolina) were established by the Spanish in 1566 and 1567, respectively. Thus, some 18 years before the “Lost Colony” at Roanoke (which disappeared, perhaps due to an Indian attack) and 40 years before Jamestown (which, since 1607, has stood to this day). The fledgling town of St. Augustine, on Florida’s Atlantic coast, had been officially incorporated in September 1565 (the first of all) and has remained continuously inhabited to the present.

[In 2018, Gustavo Jaso discussed the process of Spanish colonisation of California in some detail in an article.] [In 2019, GJ exposed, on the basis of a solid bibliography, how it was the Americans (of Anglo-Saxon origin) and not the Spanish conquistadors, who almost exterminated the indigenous people of present-day California].

Spanish colonisers trace “the dots” on the territory of the United States.

In short:

Spanish colonisers plotted “the points” in the territory on which colonisation would settle: they erected missions, built presidios (i.e. forts), planned towns and created toponymy. To this praiseworthy work of reconnoitring the territory and opening roads, we should mention the missionaries, civilian settlers, explorers, military men, doctors, botanists, engineers…

During the 19th century, with the disappearance of the Spanish Empire in the Indies (that is, in the American continent), the independence of Mexico (1821) and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 between the USA and Mexico (which meant the annexation by the United States of almost half of the neighbouring country, integrating a huge Spanish-speaking population), a new common identity, Hispanic or Latin, and a new language variety appeared. According to statistical projections, by 2050, it is estimated that between 25% and 30% of the US population will be Hispanic.

These are some of the most important historical, architectural and cultural aspects that make up Spain’s living heritage in America and which, in areas such as California, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana and Florida, have left a great influence that we are now going to develop.

1.- The image of America: colonisers and voyages of exploration; scientific expeditions.

The occupation and colonisation of the territory was accompanied by cartography. From 1513 onwards, there was a succession of campaigns or expeditions of exploration that penetrated the continent:

- Florida: in 1513 Juan Ponce de León reached Florida; in 1525 Esteban Gómez and Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón surveyed the Atlantic coast from Florida to Canada;

- Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1527 explored along the Florida coast, the Mississippi delta to Texas and much of what is now the Mexican border (Rio Grande). His strenuous itinerary – which he recounts in “La relación y comentarios del gobernador Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca de lo acaecido en las dos jornadas que hizo a las Indias” published in 1555 – was due to his desire to escape death by storms, hunger or poisoned arrows from the Indians or slavery (he spent 6 years as a prisoner of the Indians)[1]. The governor’s journey to the Indies was a great success.

- Arizona-California: The two great expeditions of Hernando de Soto (1539) and Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1540) explore the south and centre of the present-day United States, discovering the Mississippi River, the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado Canyon. Coronado reached Oklahoma and Kansas. Meanwhile, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (1542) and Sebastián Vizcaíno (1602) reached California for the first time.

- In the 18th century, maritime expeditions were undertaken to explore the Northwest coast of the Pacific, being the first to map this territory, reaching as far as Alaska. There were up to 6 expeditions to Alaska, which spread the customs of the Indians and gave an account of a previously unknown territory[2][3].

In the explorations and scientific expeditions travelled chroniclers, naturalists, doctors, cartographers, geographers, military men and Franciscan missionaries.

Thanks to these accounts, news of the climate, flora, fauna, indigenous people, linguistics, etc. were obtained. It is worth mentioning works such as the Recopilación de Leyes de los Reynos de las Indias by Carlos II, published in 1682, which includes all the provisions regulating the government, administration of justice, war and finance of the Indies. The epic poem “The Surrender of Panzacola (present-day Pensacola) and the Conquest of West Florida by Count Bernardo de Gálvez” (1785) narrates the exploits of the Spanish sailor who fought alone against the English defences of Florida.

Over the centuries, this colonising work was confronted with three major problems:

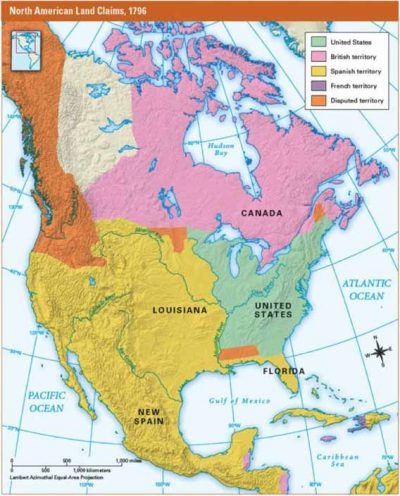

- The very complexity of internal administration given the vastness of the territory. Thus, after the end of the War of Independence of the 13 colonies (with the Versailles Peace Treaty of 1783), the Spanish domain integrated into the Viceroyalty of New Spain, recognised by the other states (France, the United Kingdom and the new nation of the United States of America) extended across the territory from the Gulf of Mexico to California, and in the north, New Mexico extended into Louisiana (almost 70% of the territory that today comprises the USA). In the construction of the territory of what we know as the United States, much of its western and southern borders were set in relation to Spain. The first boundaries between the two countries were established at the Mississippi and, with great controversy, north of Florida[4].

- The expansionist zeal of the English, French and Russian monarchies (the latter attempted to colonise the entire Pacific coast, from what is now Alaska to the present-day states of Washington and Oregon).

- The configuration of a frontier marked by clashes with the Apaches who – under pressure from the Prairie Indians – were forced to move south. Along with this, the very characteristics of the Indians, groups of tribes of diverse origins and customs, the hostility of an adverse physical environment prone to drought and famine, and the enormous distances from metropolitan centres or stable ports. Thus, in the face of the nomadic and belligerent Apaches and Comanches of Texas, a system was established with a predominance of defensive presidios, while with the Pima of Arizona and the Yuma of California the relationship revolved around the missions, with which the indigenous population was grouped and settled.

2.- Cities and Presidios or forts.

The Spanish colonisation system was always based on the figure of the city as the centre of activity and the source of economic, religious and military power. Its urban planning was based on a grid.

Thus, the new cities built by the Spaniards in the 16th century on the American continent followed a uniform model: a checkerboard of rectilinear streets, which defined a set of equal blocks that were generally square. This model was imposed from the beginning of the conquest and was codified in 1573, in the time of Felipe II, in what was the first town planning law of the modern age.

On the other hand, the Spaniards introduced two fundamental innovations in the traditional native construction of housing (which was made of mud and straw): the use of prefabricated blocks or adobes (mud baked in the sun) and the construction of interior spaces.

The core of the colonial city was located in the geometric centre of the layout and was identified by the simple operation of eliminating, or reducing, some blocks in that area. With this gesture, an empty urban space of a public nature was generated, which was to be the main square. The most important public buildings of the city, such as the church, the market or the municipal government palace, faced onto this square.

The American cities of San Francisco, Chicago or Houston, created in the westward expansion, followed the Spanish colonial city model, with a grid layout, albeit with many variations.

The Spanish founded the following cities:

- 1565. San Agustín de la Florida by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, for defensive needs. It predates the rest of the cities whose founding will be governed by the Laws of the Indies (Ordinances of Felipe II and the Compilation of Laws of the Kingdoms of the Indies in 1680).

- 1609 Santa Fe (New Mexico) by Pedro de Peralta, which largely preserved its original urban layout (razed by the Indian revolts in 1680 and redrawn in 1692) as a frontier city (far from the traditional centres of Spanish power in the Americas). Its foundation was due to the interest in consolidating the claim to unexplored territories in one of the most conflictive border areas, populated by warrior Indians who required pacification strategies developed over decades from the presidios and complemented by the work of the missions. Incidentally, it is surprising how difficult it was to survive in an arid, poorly communicated area with few mineral resources.

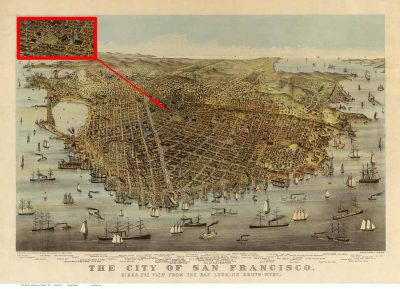

- San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, San Jose, Santa Barbara and El Paso not only bear Spanish names but have their origins in the population centres that sprang from the missions and Spanish civilian colonisation.

- The cities of San Antonio (Texas) and Gálvez in Louisiana were born from the Spanish settlements in Texas[6], concentrating in the south, on the banks of the Rio Grande[6].

- 1763. St. Louis (in present-day Missouri).

- 1781. Los Angeles (in California).

Other enclaves whose founding is due to the Spanish presence are: San Juan (on the island of Puerto Rico), Panzacola -now Pensacola-, being a military rather than urban enclave; in fact, the fortifications that defended the port are still in use by the US Navy, and New Orleans.

San Juan de Puerto Rico, founded in 1521, is the second oldest capital in the Americas (the first was Santo Domingo, founded in 1496) and belonged to Spain until 1898. New Orleans, although founded by France in 1718, grew in importance during the period of Spanish control, with the replacement (due to fires) of the original wooden structures (1762-1803) with others of stone, iron and brick that today make up the characteristic architecture of the so-called French Quarter.

The presidio or military barracks (with barely 50 men in each) completed, together with the mission and the ranchos, the set of settlement elements with which the Spanish colonial advance was structured. The Presidios of San Diego, Santa Bárbara, Monterrey and San Francisco are worth mentioning.

3.- Missions and Royal Roads

The colonising expeditions of Alta California in 1769 on the Pacific coast allowed the founding of 21 missions in a period of about 20 years by the Franciscans and, in particular, by Fray Junípero Serra[7].

But the Spaniards did not limit themselves to the coastal strips. From their settlements, they traced roads in all directions towards the continental interior. These routes were called Caminos Reales (Royal Roads). The five Spanish roads that are now National Historic Trails in the United States were already included in the map drawn by Alexander Von Humboldt in 1827 in his Atlas Geográfico y Físico de la Nueva España, and are as follows:

- Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (Royal Inland Road): it was laid out thanks to the expedition of Juan de Oñate in 1598. It linked Mexico City (capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain) with Santa Fe (capital of the province of New Mexico). One of the longest in North America, it is over 2,000 km long in Mexico and 650 km long in the USA.

- El Camino Real de los Tejas: established in 1680 to mark the Spanish presence against the claims of French Louisiana. It starts from the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro in Mexican territory and forks to cross the Rio Grande River to reach inland San Antonio and arrive to the bay. It is 4,150 km long. The 5 great missions of San Antonio are on the inland branch of this road.

- Juan Bautista de Anza Trail: Opened by Creole Captain Juan Bautista de Anza in 1774-76 to bring settlers and supplies to the Alta California settlements, it is 1,900 km long and runs from Nogales (Arizona) to San Francisco.

- El Camino Real de las Misiones de Alta California: “El Camino Real” (present-day Highway 101, north-south) links the 21 missions and the four presidios or forts of San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey and San Francisco. The bell symbolises the distance that used to be travelled in a day’s journey on horseback.

- “Old Spanish Trail” from Santa Fe (New Mexico) to Los Angeles: It is 4,300 km long. The first to travel it in its entirety was Antonio Armijo in 1829, when the American West was no longer Spanish[8]. This trail favoured the incessant traffic of traders and settlers between the towns of Upper California and those of the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico, continuing eastwards, especially in the years of the gold rush of 1848.

- The Santa Fe Trail: it provides a link between St. Louis (in Missouri) and Santa Fe (in New Mexico) and stretches 1,936 km. It was useful for the USA when they entered New Mexico in the war of 1846-1848 and continues westwards to California, linking up with the Old Spanish Trail.

4.- The Spanish contribution to American urban planning: architectural and engineering heritage

Among the works developed during the period of Spanish rule in North America (1513-1821), the following missions stand out for their architectural quality: Santa Bárbara in California, San Javier del Bac in Arizona and San José in Texas.

The best-preserved presidios are those of La Bahía in Texas and San Marcos in the city of San Agustín;

The best examples of urban civil architecture are the Governor’s Palaces in St. Augustine and Santa Fe, the Cabildo in New Orleans and the Customs House in Monterey (California). It gave rise to the so-called “colonial” style, especially present in the Southwest and California, also known as Spanish Colonial Revival or Mission Revival reflected in the characteristic haciendas; the use of white walls and ceramic tile roofs continued into the 18th and 19th centuries (example: the Santa Barbara County Courthouse, by architect William Mooser III).

Even after the end of the Spanish presence in the USA, Spanish architects and engineers continued to work in the area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One such architect is Rafael Guastavino, who introduced the vaulting system, the bóveda tabicada or catalana. Thanks to the advantages of this system (light, resistant and economical), his company, together with the best architects of the time, built nearly a thousand buildings throughout the country (e.g. the Avery Library, Columbia University NY).

City Hall subway station in New York City, closed since 1945, featuring examples of Catalan vaults by Gustavino.

In the most current architectural iconography of the American city, the following are worthy of note: Josep Luis Sert, Rafael Moneo or Ignacio Avalos, the three directors of the Department of Architecture of the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Conclusions

It is difficult to summarise the magnitude of Spain’s presence in the United States. Suffice it to mention that, on the occasion of the commemoration of the centenary of US Independence in 1883, the 129 most important Spanish expeditions prior to 1783 recorded in the Archives were mentioned. From 1783 until Spain’s withdrawal in 1821, there were several others.

Spain’s built work in the United States constitutes a great historical heritage: forts, irrigation ditches, other hydraulic constructions, public buildings, missions, etc. But this work does not end with the colonial presence, but continues to this day through the work of Spanish architects and engineers, right up to the present day. The New York Subway, roads and highways, a solar power plant in Nevada, etc. allow Spain to be considered one of the first and main contributors to the American national heritage.

Notes:

- In his story Naufragios, he recounts what he found on his voyage: scattered populations of backward people who could barely subsist, with makeshift shelters made of mats, with hardly any social structures beyond clan or tribal relations. He experienced fierce experiences of raging storms, and of violence, cannibalism and slavery. In what is now Tampa, the first point of arrival, he describes the terrain he passes through, the flora (walnut and laurel trees, sweetgum trees, cedars, junipers, oaks, pines and oaks and cornfields) and the fauna (rabbits and hares, bears and lions). They were enslaved by the Indians for 6 years in Galveston.

- Nutka Territory (or St. Lawrence of Nutca) included Nutca, Quadra and Vancouver, and Flores islands and others in the Strait of Georgia, the entirety of the present-day Lower Mainland in British Columbia and the southern half of this Canadian province; as well as much of the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana in the United States. It was governed from Mexico City from 1789 to 1795, when it was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spanish under Esteban José Martínez built Fort San Miguel in Nutka Bay, now Vancouver Island.

- These were the scientific voyages to map the Pacific coast in 1770 (where the naturalists Mociño and Maldonado studied the characteristics of the area) or Malaspina’s scientific expedition, which sought to verify the existence of a supposed passage that connected the Pacific and Atlantic oceans at 60º north latitude. The Pacific coast was explored in an ambitious project led by the naval captains Alejando Malaspina and Luis de Bustamante, who from 1789 to 1794 travelled around the Spanish dominions in America, Asia and Oceania, drawing up maps and collecting a complete sample of the American flora. In 1791, the corvettes Descubierta and Atrevida, which had sailed north from Acapulco, arrived at Cape Engaño in present-day Alaska. The main objective was to reconnoitre Yakutat Bay, where there is a glacier called Malaspina.

- The Viceroyalty of New Spain was a territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established in much of North America by the Crown during its rule of the New World between the 16th and 19th centuries, known as the Mexican colonial period. It was created after the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the main event of the Conquest, which did not really end until much later as the territory of New Spain continued to grow northwards at the expense of the territories of the indigenous peoples of the desert. The viceroyalty of New Spain was officially created on 8 March 1535. Its first viceroy was Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco and the capital of the viceroyalty was Mexico City, established on the site of ancient Tenochtitlan. The viceroyalty of New Spain came to encompass Spain’s territories in North America, Central America, Asia and Oceania.

- The territory of New Mexico changed its sovereignty in 1821 with Mexican independence. A brief struggle for independence between Texas and Mexico began years later, ending with Mexico’s unrecognised signing of the Treaty of Velasco in 1838. The independence of the Republic of Texas and its annexation to the USA provoked the first war between the United States and Mexico in 1846-1848, which ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, resulting in the loss of more than half of the Mexican territories in the border area, including New Mexico and its capital Santa Fe.

- As a consequence of the undetermined boundaries of Louisiana, ceded by the French Crown to Spain and then sold by France to the United States, diplomatic conflicts between the Spanish Crown and the American Union took place, ending with the Treaty negotiated by President John Quincy Adams and Luis de Onis between 1819 and 1821 … According to the Treaty, the USA gave up its claim to Texas as part of Louisiana in exchange for recognition of its possession of Florida.

- In addition to its religious motivation, there was a strategic purpose: the Pacific territory was threatened by Russian traders who, under the pretext of having exhausted the otter beds near Alaska, were scouring the coast for Russian settlements in the vicinity of San Francisco. The creation of missions alongside existing settlements and presidios was able to contain the foreign presence. With them along the coast, the two Californias, the Upper and Lower Californias, were linked.

- Armijo made his journey with 60 men and 100 mules and in 86 he reached his goal, which was to trade blankets and textiles he was carrying from New Mexico for thousands of horses that were surplus to requirements in California and cheap.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1572 Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva founded the town of Guaduas (Colombia).

- 1578 Brunei becomes a vassal state of Spain.

- 1672 Spanish comic actor Cosme Pérez ("Juan Rana") dies.

- 1693 Painter Claudio Coello dies.

- 1702 The Marquis de la Ensenada was born.

- 1741 Spanish troops break the siege of castle San Felipe in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia).

- 1844 The Royal Order of Access to Historical Archives was promulgated.

- 1898 President Mckinley signed the Joint Resolution, an ultimatum to Spain, which would lead to the Spanish–American War.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021