Source:Libertad Digital

The centre was the only political sector for which democracy and the Republic were ends in themselves, as a constitutional legal system and not as a system of radical reformist, social or cultural objectives.

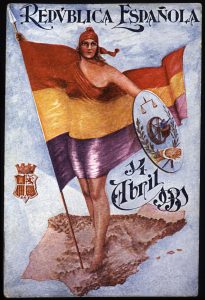

Although technically the Republican alliance did not win the municipal elections of 12 April 1931 and there was never a plebiscite or referendum to legitimise the resulting Republic, the legitimacy of the regime born on 14 April 1931 was widely accepted in Spain. The Republican alliance had failed in its attempt to carry out a military pronunciamiento in December 1930 but claimed victory in the municipal elections because it won significant majorities in the larger cities, where mobilisation was most intense. Alfonso XIII chose not to question the result obtained by the Republicans and Spanish public opinion overwhelmingly accepted the legal basis of what was overwhelmingly understood to be a democratic republic.

In retrospect, it can be argued that a democratic reform of the parliamentary monarchy would have provided a more solid foundation for this new democratic system than the leap into the void represented by the new regime, but the Republic maintained a relative continuity with monarchical legal structures and institutions, except for the fundamental separation of Church and State. During the first months, the new regime encountered opposition only among a small minority of monarchists and communists, on the extreme right and the extreme left. Even the revolutionary anarcho-syndicalists of the CNT at first reconsidered their disagreement with the new regime, whose bloodless implementation was seen as an example of Spain’s new civic maturity, putting a definitive end to the previous period of civil wars.

Between 1931 and 1932, the vast majority of Spanish political society was defined by five main political sectors: the centre, the moderate left, the moderate right, the extreme left and the radical right. The centre was made up of republican democrats and liberals, represented above all, though not exclusively, by the Radical Republican Party, led by the veteran Alejandro Lerroux. Other major figures in the centre were Niceto Alcalá-Zamora (who became President of the Republic) and Miguel Maura, both practising Catholics, at the head of small independent parties.

The moderate left was mostly composed of the “left republicans”, also called the “bourgeois left”, and included different parties, among which Izquierda Republicana (Republican Left), led by Manuel Azaña, became the most important. The moderate left differed from the centre above all in its insistence that the Republic should consist of a series of radical cultural and institutional reforms, reforms which, rather than the rule of law, represented the “essence” of the Republic.

The moderate left was mostly composed of the “left republicans”, also called the “bourgeois left”, and included different parties, among which Izquierda Republicana (Republican Left), led by Manuel Azaña, became the most important. The moderate left differed from the centre above all in its insistence that the Republic should consist of a series of radical cultural and institutional reforms, reforms which, rather than the rule of law, represented the “essence” of the Republic.

The extreme left, or revolutionary left, was initially led by the CNT, which did not opt for direct, violent revolution until late 1931, but also included the tiny Communist Party of Spain (PCE – Partido Comunista de España) and other minor communist parties.

Straddling the moderate and revolutionary left was the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE – Partido Socialista Obrero Español), which became part of the initial ruling coalition along with the left-wing Republicans and the centrists. For the socialists, republican democracy was not a goal in itself, but a stepping stone to a socialist economy and a socialist republic. In 1931, the PSOE aligned itself with the moderate left, assuming that political democracy would produce the desired results, even if they did not have a defined alternative in case it did not.

By the end of 1932, the moderate right was composed of the first major Catholic political party in Spanish history, the Spanish Independent Rights Confederation (CEDA-Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas). Although the left wing of the CEDA defined itself as Christian Democratic in its values and orientation, this party was not, in general, a Christian Democratic party, as it sought to transform the political regime into a system of Catholic corporatism like those being organised in Portugal or Austria. However, because of its commitment to legality and its rejection of violence, the CEDA firmly represented the thesis of the moderate right.

The radical right was, at first, made up of a few monarchist minorities who were hardly relevant. The alfonsinos, supporters of the deposed king, ended up organising themselves into the Renovación Española party, which rejected the principles of parliamentary monarchy in favour of the establishment, rather than the mere restoration, of a corporatist, authoritarian and Catholic monarchist regime of a “neo-traditionalist” nature. (This group became the first precursor of the subsequent Franco regime). The original traditionalist monarchists, or Carlists, were strengthened by the Republican attack on Catholicism, but, although they continued to be active, they had little support outside Navarra.

The first groups to reject the new regime by violence and insurrection were the anarcho-syndicalists and the communists. The weakness of the latter hindered their projects, but the FAI-CNT activists launched three different revolutionary insurrections in January 1932 and in January and December 1933. Each one spread over half a dozen provinces, and neither their lack of organisation nor their nil chance of success prevented them from killing more than 200 people.

Some small sectors of the radical right also organised a military revolt, led by the eminent General José Sanjurjo, which broke out on 10 August 1932. The so-called “Sanjurjada” was ignored by most of the army and only had some success in Seville for a few hours. Ten people died in this failed coup. During the first three years of the Republic, therefore, the extreme enemies of this system of government enjoyed little support. The four attempted uprisings – three by the extreme left and one by the extreme right – never posed a serious threat to the new regime.

As the Republican government carried out a series of important reforms between 1931 and 1933, the ruling coalition was gradually weakened. First, most of the centrists left, citing the socialists’ incompatibility with a republicanism constitutionally based on democracy and private property. In the end, in September 1933, the alliance between the left republicans and the socialists broke down, leading to new elections that same year.

In these elections, the Socialists refused to ally themselves with the Left Republicans, and public opinion had already begun to react negatively to the results of Republican reformism, especially with regard to its denial of full civil rights to both Catholics and the Church. In the new elections, the CEDA won a plurality, if not a majority of the votes, becoming the largest party in the Cortes, followed by the Radicals. The outcome of these second elections was almost diametrically opposed to that of the first elections in 1931.

The leaders of the left-wing Republicans and the Socialists responded by demanding that President Alcalá-Zamora cancel the results of the vote and allow them to modify the electoral law so that, in the new referendum, the electoral victory of the left would be guaranteed. They did not allege the illegality of the vote; they only objected that the right had won. They rejected the basic principle that constitutional democracy depends on the rules of the game and the rule of law, what has sometimes been called “fixed rules and uncertain outcomes” and insisted on guaranteeing themselves an outcome – power for themselves – that could only be achieved by endlessly manipulating the laws.

While the CEDA had accepted electoral laws drawn up by its left-wing opponents, the moderate left claimed that the Catholic party could not be allowed to win the elections – even by applying the laws of the left – because the CEDA intended to introduce certain basic changes in the republican system. The left itself had just fundamentally changed the Spanish system, while the socialists intended to go much further, introducing full socialism, and yet the left parties argued that the moderate right had no right to win an election and implement its own changes. The left insisted that the Republic was not a democratic system equal for all, but a special regime, identified with the moderate left and not with the wishes, expressed at the ballot box, of the majority of Spanish society, which, depending on their political content, could be ignored.

Not surprisingly, President Alcalá-Zamora rejected four different requests from the moderate left to cancel the election results and change the laws ex post facto. At least in 1933, he insisted on fixed rules and uncertain results. Moreover, the fact that the moderate left, largely responsible for the laws and reforms of the Republic, disdained electoral democracy as soon as they lost the elections meant that the prospects of the new regime becoming a democracy were extremely limited. It was not possible in principle for democracy to depend on the centre, and perhaps on the moderate right, for although the latter accepted legality, its ultimate goal was not the maintenance of the democratic republic but its conversion into a different kind of regime, and it was highly unlikely that the liberal centre democrats, who barely had 20% of the popular vote, could maintain a democratic regime on their own.

However, quite a few modern political systems have taken their first steps in a climate of uncertainty, so the end of 1933 did not doom the Republic, for there could have been several positive developments: the centre could have grown or strengthened, and the moderate right could have moved towards the centre or the moderate left become more democratic, accepting equal rights for all.

Unfortunately, none of this happened: the centre became smaller and weaker, the moderate right did not move decisively towards the centre and the moderate left became more exclusionary, insisting on a left-only Republic, while a large part of the socialist movement embraced violent revolution.

Chapter of the book 40 preguntas fundamentales de la Guerra Civil (La Esfera de los Libros, 2006)

Share this article

On This Day

- 1503 Battle of Cerignola (Italy).

- 1522 Santiago de Cuba is granted the city status by Carlos I.

- 1589 Margarita de Saboya is born.

- 1611 Archbishop Miguel de Benavides founded the University of St Thomas in Manila.

- 1777 José Primo de Rivera, Hero of the Sieges, was born in Algeciras.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021