Source:piomoa.es

Since their appearance on Earth, human groups have travelled to expand over most of the emerged planet, whether by a semi-conscious impulse to explore, to search for resources to live on, driven by climatic variations or other causes. Of these migrations, nomadic movements and invasions over thousands of years before history, that is, before the so-called Neolithic revolution, there are scattered archaeological traces and other more verifiable genetic, linguistic and more general cultural traces. It is somewhat difficult to explain how the human physical and mental constitution, being essentially the same, has given rise to such strong cultural differences that they have been seen as incompatible with each other even in regions in close proximity to each other and with similar physical and climatic characteristics.

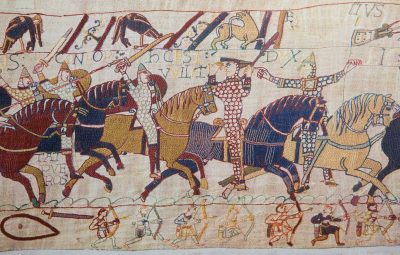

What is certain is that these migrations have been accompanied by clashes, invasions and conquests: some groups have subjugated others, sometimes exterminating them, or mixing with them. Fighting and invasion have been frequent, even if they have been followed by periods of mingling or peaceful dissolution of the invaders among the invaded. Often, too, the invaders have been much smaller but better-structured groups than the invaded. The Romans who conquered Spain were very few in number, as were the Visigoths or the Arabs. The same can be said of the Franks, the Angles and Saxons or later the Normans who imposed themselves on the others in England after the Battle of Hastings.

As every human society is a culture, i.e. a set of structuring ideas, rites and religious, political, economic and artistic actions, elaborated in a different spirit by each somewhat large human group, each tends to assume itself superior to others, and its military dominance is often seen as the demonstration of such superiority. The opposite may well be true, however. Thus, the Roman invasion of Hispania (or the rest of that empire) came from a cultural superiority which it transmitted to numerous “nations”, unifying them in that sense. By contrast, the invasions that destroyed the Western Empire brought with them an age of barbarism, with the destruction or ruin of cities, libraries, institutions of law and learning, crops, industry, trade and communications. It was the age of survival or Early Middle Ages, in which what we now call European civilisation may have died in embryo, and was only overcome after five centuries of gruelling effort from the 11th century onwards, when the Romanesque and Gothic periods ushered in the Age of Settlement or Late Middle Ages. Still in the 13th century the Mongol invasion seriously threatened civilisation, which was saved almost by chance.

Invasions and conquests are thus one of the determining phenomena of history, consequences of the diversity or opposition of group interests and feelings, and of their cultural elaborations. It must also be said that when we speak of European civilisation at the time we are referring in a special way to the Christian unifying element, and that the end of foreign invasions and conquests did not mean the end of invasions and conquests between the various European nations. These have continued into the 20th century itself, and if they have ceased since the end of the Second World War, it has been due to general European weakness. Another manifestation of this has been the attempt by the once most powerful European nations to retain their colonial empires, in which they have reaped little more than defeat and failure.

When we speak of the conquest of America we must understand it in this general historical framework, and it is from this point of view that it must be approached.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1483 The conquest of the Canary Islands is completed.

- 1521 Hernán Cortés starts the "Conquest of Mexico".

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021