Source:ABC

Tomorrow the statue of Blas de Lezo will be unveiled in Madrid, in the Plaza de Colón. There is no better day to remember the most memorable battle of his career.

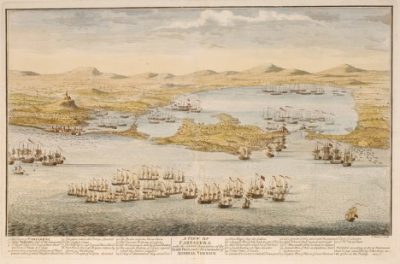

On 13 March 1741, the astonished New Grenadians living in Cartagena saw 135 sails on the horizon, of which 36 were ships of the line and the rest transports. And so began the great Cartagena de Indias play.

In March and May of the previous year, Vernon had bombarded the city of Cartagena de Indias, then under the command of D. Blas de Lezo, and the heroic “Mediohombre” (half-man) took measures to improve the quality of bastions and batteries and the effectiveness of their fire fields.

Admiral Edward Vernon, painted by Phillips

When the viceroy of New Granada, Don Sebastián de Eslava, learned that Vernon was coming in force to try to conquer Cartagena, and as the city was without a military governor, he decided, to his credit, to take personal command of the defence, so that Don Blas de Lezo, head of the apostadise and squadron (six ships of the line) became his immediate subordinate.

Eslava initially set up a sealine defense in which, under the orders of Don Blas de Lezo, all the forts and castles on the coast immediately around Bocachica, the passage finally chosen by the enemy to force their way into the bay, were integrated. Bocagrande, at that time, was impracticable due to lack of draught, and the proximity of the Tesca marsh and the Juan de Angola channel to the Boquilla made it inadvisable for Admiral Vernon to disembark there as originally planned.

Still of the reconstruction of Cartagena de Indias

The colonel of Engineers D. Carlos Desnaux (whom Lezo called “de Enaut”) was appointed second to Don Blas, with his command post in the castle of San Luis de Bocachica, and the captain of the Marine Battalions D. Lorenzo de Alderete y Barrié was appointed second to Don Blas, with his command post in the castle of San Luis de Bocachica. Lorenzo de Alderete y Barrientos took command of the forts of “San Felipe” and “Santiago”, reporting directly to the former.

Don Blas anchored four of his ships in Bocachica, hoisting his insignia on the Galicia from which he directed operations during the first 17 days of the siege, fundamental days that undermined English resistance due to the tenacious Spanish defence, the damage they suffered from the fire of ships and bastions, and the unhealthy tropical climate. The other two ships were anchored off Bocagrande. Don Blas used various merchant ships, which were in the bay, for various logistical and liaison tasks between his different forces, and even armed one of them with 30 cannon.

View of Cartagena according to the 3D rendering

Development of operations.

The enemy’s initial plan was to land on the south bank of the Boquilla and, after fording the Juan de Angola channel, take the Quinta and attack the castle of San Felipe de Barajas or San Lázaro from there, while another detachment took over the mouth of the Sinú, at Pasacaballos, to completely cut off supplies to the city and thus be able to surrender it by starvation.

Vernon sailed from Jamaica on 07 February 1741 (the departure operations had begun on the 3rd when the 1st of the 3 divisions into which the squadron was organised left) in search of Guadeloupe to make sure that the French squadron was in Port Louis and probably with the intention of destroying it so as not to leave enemies to windward but, after certain errors in the information he gathered, he was certain that Antin had sailed for Europe on the same day that he had sailed from Jamaica. After assembling a council of war of general officers, he sailed for Cartagena.

View of Cartagena de Indias, according to the rendering exhibited at the Naval Museum as part of the exhibition dedicated to the Mediohombre.

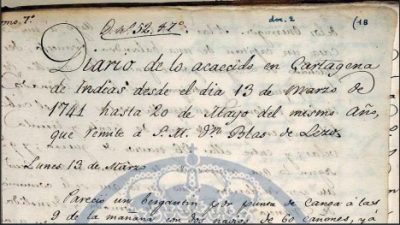

On 9 March, Vernon sent Captain Knowles with the ships Wermouth and Experiment, and the corvette Spencer, to scout the coast of Cartagena to prepare for the landing and choose anchorages for the squadron and convoy. Knowles’ reports, which would surely indicate the marshy terrain surrounding the Tesca marsh and the lack of sheltered anchorages on the coasts immediately around the beautiful bay, led to a change in the initial plan, with the first priority being the forcing of Bocachica and the occupation of the bay, before the definitive assault on the Plaza. This Knowles division anchored on the 13th of the same month in the shelter of Punta Canoa. That same day, Blas de Lezo began to write his diary, in which he recorded what he had ordered and arranged to prepare the defence and the reports and orders he received, the friction and disagreements he had with the Viceroy and the details of the operations.

On the 15th, the English squadron and the convoy of troops were anchored at Playa Grande. Don Blas de Lezo, after receiving the viceroy’s orders, went to Bocachica the following day, embarking in his flagship, and found the bastions and castles: “…lacking in everything, and I immediately sent provisions and people, gunpowder, bullets, cartridges…“ That same day, the 16th, the enemy made a diversion on the Boquilla with multiple movements of launches and boats, but the Spaniards immediately realised the threat and D. Blas worked to improve the state of defence of his front.

On the 20th, Lezo clearly perceived that the enemy would try to force Bocachica and, indeed, at 11:00 that same day, two English ships began to beat the forts of San Felipe and Santiago, beginning the Bocachica operations that would end on the 5th of May with the withdrawal of the surviving Spanish forces to the city of Cartagena and the sinking of the four ships that had pushed the defence of that mouth to the limit of the impossible. The haste with which the order to withdraw from the fort of San Luis de Bocachica was given partly spoiled the disposition that Lezo had taken to seal off the channel with the sacrifice of his ships; nevertheless, it was a hard feat of seamanship for the English to enter the bay by spying and helping themselves with smaller vessels.

Among the many criticisms that Blas de Lezo makes in his diary about this phase of the battle, the most important is the one that shows his clear vision of the weakness of the amphibious operations at the very moment of landing, the moment when the defender must do his utmost to prevent the assailants from stepping on the shore. Using the reserves with agility, multiplying in order not to ignore the landing of any detachment, preventing the landing of the siege artillery …. felling to prevent the enemy from taking shelter in the forest, sieving to protect the servants from their own artillery, and above all “ATTACKING” the first detachments that landed with energy and decision, was what he recommended and which, it seems, was not listened to, although his stubborn obstinacy in defence contributed to the subsequent triumph at San Lázaro.

A View of Cartagena with the several dispositions of the British Fleet under the Command of Admiral Vernon. Isaac Basire. London 1741

The seventeen days of resistance in Bocachica, plus the difficulties that the British ships had in entering the port, meant that the bulk of the British troops could not disembark at Tejar de Gracia until Sunday 16th April. In that month and three days, in addition to the numerous casualties in combat, the British force suffered greatly from disease and the terrible tropical climate to which it was not accustomed.

Sunday 9 April is quite decisive in the history of this defence of Cartagena and the decisions taken that day by Viceroy Eslava caused deep bitterness in Don Blas de Lezo, who stated that: “…[for him] it was very sensible to abandon the castle [Grande, on the recommendation of Desnaux] and ships without the corresponding defence and without the enemies specifying us, to which he replied that the only remedy [as everyone said] was that if the two ships were sunk, the channel would be closed so that the enemies could not enter… to beat this city…”

Vernon, after softening as much as he could of the defences of the forts that protected the city to the SouthWest, ordered the landing on the island of Manga for the operation that he planned to complete with the capture of Cartagena. At 0200 on Sunday 16 April, 1,400 men disembarked and were joined on land by 200 Americans and a detachment of negros, who occupied La Quinta and the convent of La Popa, and then prepared the assault on San Felipe de Barajas or San Lázaro. Given the time elapsed since the beginning of the operations, the impatience of the English admiral, and his serious disagreements with the chief of the landing force General Wentworth (much harsher and ruder than those suffered on our side) they did not wait to have the siege artillery ready to open the breach and the English, with their characteristic bravery, did not wait to open the breach, launched themselves uphill, in the early hours of the morning of 21st April, to assault the castle of San Lázaro on the side of the Cabrero ravine, which was defended by two marine pickets and three from the Aragón regiment, and were defeated by our forces. Don Sebastián Eslava, decisively supported by Lezo despite the disagreements, judiciously used his scarce reserves and, at 07:00 am, the enemy fled precipitously, leaving 170 dead and 459 wounded on the field who, according to the English account, were treated with the utmost humanity by the Spaniards.

On 30 April, at the request of the British command, an exchange of prisoners took place and through these the Spanish commanders learned that the British had planned a second attack on San Felipe de Barajas but gave up because the troops refused to carry it out: “… so it was necessary to withdraw them from the land after decimating them, 50 men passing through the arms for manifest disobedience to the enemy”. Perhaps the figure is exaggerated but there is no doubt that the British were defeated, they had lost the will to fight.

Vernon, to cover the avalanche of criticism that he foresaw was coming his way, because after entering the bay he thought the case had been solved and he had dispatched a frigate to London communicating the victory and the famous coins minted with the “Spanish humiliation” had begun to circulate, had the battered Galicia armed as a floating battery and mounted a bombardment that was so energetically repulsed that the poor former flagship of Lezo went to the bottom.

In view of the impossibility of taking the city, the British withdrew and, after reembarking the troops, the sick and wounded, set sail for Jamaica.

The scurvy at sea, the lack of water, which was partly alleviated when the English squadron entered the bay, the mosquitoes on land, and the well-known tropical diseases: yellow fever (or black vomit), malaria, tropical dysentery, etc., softened up the English more than they could have imagined. The logistical lines were not well set up, the detachments sent into the interior to provide fresh food were unsuccessful, the arguments over the distribution of water and food between sailors and troops undermined the morale of the combatants. In any case, it is worth admiring the brave English charge, uphill, in the middle of the night and with the equipment to scale the walls of San Felipe de Barajas on their shoulders, which, made by infantrymen, recalls the futility of that made by their cavalry at Balaclava in the following century.

Statue of Blas de Lezo that Don Juan Carlos will unveil on Saturday 15 November in Madrid. PHOTO José Ramón Ladra

The total losses of the British were estimated at:

Six ships set on fire by themselves as they were rendered useless.

- Seventeen ships damaged.

- 9,000 casualties.

- 18,000 cannonballs and 6,068 bombs expended.

Spanish losses:

- Six ships self-sinking.

- Six hundred casualties

On 8th and 28th June, Viceroy Eslava wrote letters censuring and warning H.M. the King against Don Blas de Lezo, the result of which was the R.O. of 21st October 1741, dismissing Lezo who, as he had died on 7th September of the previous month, never found out about such an injustice.

The Navy has always remembered with pride the legendary figure of Don Blas de Lezo, a French-trained midshipman, a loyal Spanish officer, devoted to his King and his homeland, a Basque born in one of the most generous nurseries of the Royal Navy. A gunboat, a cruiser and a destroyer bore his name in gilded brass letters on wooden metopes painted in red, perhaps to evoke the much blood he shed during his forty years of service. His name is currently borne by a frigate of the “Almirante D. Juan de Borbón” class.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021