Source:A orillas del Potomac

In 1798, the British country doctor Edward Jenner obtained the first institutional recognition for his newly devised (1796) smallpox vaccine; the Royal Society finally published its documentation, although the scientific and social controversy continued for several more years. It was the birth of modern immunology and the first vaccine.

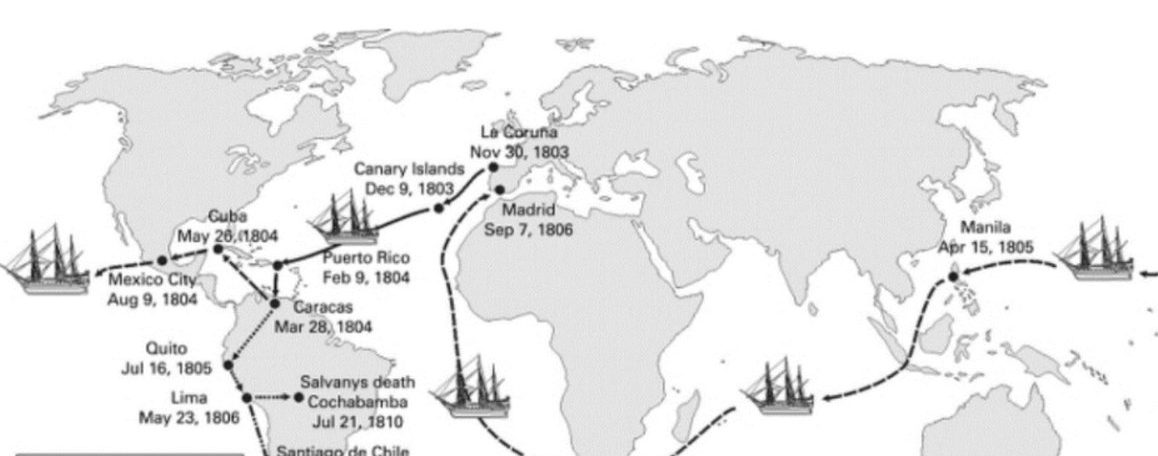

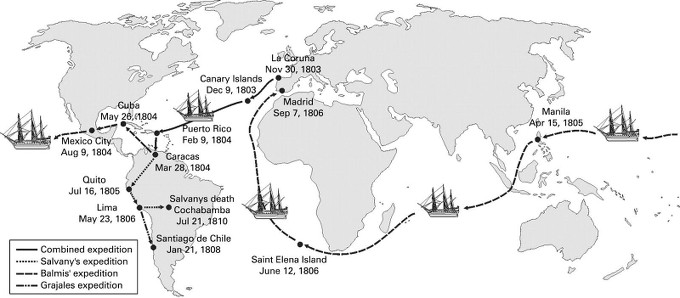

Route of the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition. 1803 – 1806.

Only 5 years later (in 1803), the Spanish Crown chartered a ship with three doctors, two practitioners, four nurses and twenty-two children (aged 3 to 9 years). For almost 3 years (until 1806), they vaccinated many hundreds of thousands of people, from two continents: America and Far East Asia.

More importantly, they taught local doctors to continue to do so, creating specific institutions (Vaccine Boards, which in several cases eventually became national vaccination institutes). They vaccinated both the settlers and the local indigenous people. The disease did not distinguish between social classes or races.

Although the sea voyage ended in Spain in September 1806, part of the original medical team continued the work of vaccination and teaching in the territory of present-day Bolivia and, later, present-day Chile until January 1812. This makes a total of 8 years and 2 months of that health campaign: 1803 – 1812.

Opinion of vaccine discoverer Edward Jenner

The discoverer of the smallpox vaccine himself, the Briton Edward Jenner, wrote about this expedition: “I cannot imagine that the annals of history can provide a nobler and more extensive example of philanthropy than this one.”

It is regarded as the first international sanitary expedition in history.

Alexander von Humboldt’s opinion

Alexander von Humboldt, the illustrious Prussian geographer and explorer, wrote in 1825: “This voyage will remain the most memorable in the annals of history.”

The British deployed a vaccination campaign on a few of their Caribbean islands in the early 19th century, but its extent is not remotely comparable to the Spanish expedition, nor were specialised institutions set up to continue the effort.

According to Spain’s Revista de Historia Naval (link in Spanish), “after that medical enterprise, more than a hundred years had to pass before the League of Nations [1920 to 1946, the predecessor of the United Nations] launched new global health campaigns similar to that one in the [early] twentieth century.”

Its official name was the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition, personally promoted by King Carlos IV.

Before going any further, it occurs to one to wonder why this and many other exploits carried out in the past by Spaniards are not recounted in our country’s schools. Stories of lesser importance and significance are explained to all the schoolchildren of France and the United Kingdom, which is the right thing to do for a self-respecting nation.

Origin and approach of the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition

Its aim was to reach every corner of the Spanish Empire with the smallpox vaccine, as the high mortality rate of the virus was causing the death of thousands of children.

In my article of 25 September 2018, I discussed the severe impact that infectious diseases from Europe had on the indigenous people of the Americas.

It was only in December 1800 that the vaccine had arrived in Spain (Puigcerdá) for the first time, from Britain. Three years later the Royal Expedition was launched, which was a prodigy of speed.

“It is estimated that this disease caused the death(link in Spanish) of the sufferer in 30 percent of the cases, while the same percentage of those who managed to overcome the disease had important sequelae for the rest of their lives”, normally paralysis of the legs.

“Recent historical studies have shown that at the beginning of the 18th century (link in Spanish) – coinciding with years of unusually low temperatures that affected the Old Continent, a period historically known as the “Little Ice Age” – around 400,000 people died annually in Europe due to smallpox.”

The King of Spain supported and paid for the health campaign

King Carlos IV supported and financed with public funds the Court physician, Dr Francisco Javier Balmis, from Alicante, in his idea of a general vaccination of children throughout the Empire, as his own daughter, the Infanta Maria Teresa, had suffered from the disease and died shortly afterwards.

Along with Dr Balmis, Dr Salvany, who ended up dying in Cochabamba (now Bolivia) in 1810, while continuing his work of vaccination and teaching in 1810, also deserves to be remembered.

The military doctor Santiago Granado and Dr Grajales continued the expedition along the Pacific coast as far as Chile. Dr Grajales was the one who extended his work the longest, until January 1812, in Chilean territory.

The royal decree issued by King Carlos IV concerning the Vaccine Expedition arrived in New Spain in August 1803, addressed to the viceroy of Mexico … The royal decree stipulated, among many other detailed instructions, that “the vaccine would be transported by means of children (link in Spanish), who would be inoculated successively during the journey until they reached the Indies”. This operation was called “arm to arm” and was considered the safest way to preserve and enforce the efficacy of the vaccine at the time of its application.

The 22 Spanish children

Of the 22 Spanish children who set off from La Coruña, only one would die, during the first journey.

In his ambitious vaccination plan, the far-sighted doctor from Alicante, Balmis, had the happy idea of taking 500 copies of his Tratado histórico y práctico de la vacuna, which were distributed throughout the main cities of America.

One of the main expenses that the expedition had to face was the purchase of the first-aid kit. This was composed of pieces of canvas for vaccinations, 2,000 pairs of glasses to keep the bovine fluid, a pneumatic machine, 4 barometers and 4 thermometers.

Once the expeditionaries arrived in America and other Spanish territories, the local Spanish authorities (who had been informed directly from the Court) were obliged to provide services to the medical team and the other members of the expedition, including the children.

As was to be expected, some authorities did a better job than others.

Development of the international health campaign

The Expedition began with the departure of the ships from La Coruña on 30 November 1803.

The port of La Coruña was chosen because it was the port from which the Navy’s mail ships regularly departed for Havana, Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

The geographical scope of the expedition covered much of the American continent: the Caribbean, New Spain (now Mexico), Central America, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Bolivia and present-day Argentina. In the present-day USA, it appears to have operated only south of the present-day state of New Mexico.

In fact, before making the Atlantic leap, the expedition began its work in the Canary Islands.

Route of the expedition in the Philippines. 1805

It also fanned out to several of the Philippine islands, reaching as far as the cities of Macau and Canton in China. Finally, it carried out its charitable work on a British island in the South Atlantic.

San Juan de Puerto Rico was the first Caribbean port where they anchored and where they undertook their work. From there, they travelled to Caracas, “in whose territory of influence he created, on 23 April 1804, the first Vaccination Board of the American continent”.

The health campaign was split into two

Due to the enormity of the territory to be covered, Dr Balmis decided to split the expedition into two. In fact, each of the two legs of the expedition split into smaller ones in order to be able to extend its work. This work was particularly arduous in the interior, where communications were very poor.

“Once in La Guaira, on 8 May 1804, Balmis (director of the expedition) and Salvany (deputy director) split up. The former continued, together with half the team and Isabel Zendal, through North America, via Cuba, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and from there, following the route of the Manila galleon, to the Philippines and China.”

“Dr. Salvany, for his part, continued with the other half of the Spanish health workers who had sailed from the port of La Coruña, to take the vaccine to the territories of Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile.”

Although the sea voyages of the Expedition ended on the Iberian Peninsula in September 1806, part of it (led by Dr Salvany) continued until his death in July 1810 in the city of Cochabamba (in the Bolivian highlands).

In addition, until January 1812, the group of Dr Santiago Granado (military) and Dr Grajales continued throughout present-day Chile. “Grajales’ group vaccinated, established vaccination boards and created vaccination plans throughout the Captaincy General of Chile”.

Tour of the expedition in the Philippines. 1805

They also vaccinated on the British island of Saint Helena

On its return voyage to Spain from the Philippines, the ship crossed the Indian Ocean, rounding the Cape of Good Hope, that is, the southern tip of Africa, entering the southern Atlantic.

When the ship arrived at the island of Saint Helena, situated at a considerable distance off the coast of Angola, they found that the smallpox vaccine was not known there. Despite the fact that this island was (and still is) administered by Great Britain, Dr Balmis did not hesitate to carry out vaccinations.

“Of all those involved in the Royal Philanthropic Smallpox Expedition, only its director, Francisco Javier Balmis, was able to return to Spain [in 1806] and be received as the hero he was.” Not that the others all died early, but – as with the children – they remained in Mexico or other Spanish cities.

Long-term effects of the Royal Expedition

In 1980 – one hundred and seventy-four years after the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition – the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared smallpox eradicated from the planet.

More specifically, and according to Dr José Tuells, director of the Balmis Chair of Vaccinology at the University of Alicante, “the fact that America was precisely the continent where smallpox [1971], polio [1991] and measles [2002] were eradicated first was largely due to the Balmis expedition and the Vaccination Boards that the Spanish doctor promoted on the continent…”

The “first time” this happened was in the developing continents (including Central and South America), as Europe, the USA, Canada, Japan and Australia had eradicated these diseases earlier.

Bibliography

The most complete work available in recent years is the extensive joint study by university professors José Tuells Hernández (Univ. Alicante) and Susana Ramírez Martín (UCM. Madrid), entitled “Balmis y Variola” (link in Spanish), published in 2003 by the Consejería de Sanidad de La Generalidad Valenciana. It contains an extensive bibliography.

These two authors, separately, have also published articles on this subject.

Also interesting is the article Balmis y la Real Expedición Filantrópica de la Vacuna (1803-1806) (link in Spanish), by the reserve frigate ensign Luis Negro Marco, published in the Revista de Historia Naval. 2018. Nº 140.

The novel A flor de piel, by Javier Moro, 2015, repeatedly alludes to this Royal Expedition.

María Solar’s recent novel (2017) Los niños de la viruela (Os nenos da varíola, in Galician), published by Edit. Anaya, is about the 22 children who left Spain in 1803. Children to whom the City Council of La Coruña dedicated a monument in the city, indicating their names.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1528 Prince Felipe is sworn as heir to the Spanish kingdoms in Madrid.

- 1593 The city of San Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina) is founded by Francisco Argañaraz y Murguía.

- 1776 Battle of Lexington and Concord (United States).

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021