Source:El cierre digital

In the work “1936: Fraud and Violence”, authored by professors Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García, two historians who, after 5 years of research, have dismantled all the fallacies that had been written about the resounding triumph of the Left in those elections that led a few months later to the Civil War. According to the historian Stanley G. Payne, the work represents “the end of the last of the great political myths of the 20th century”.

Scraped census and changed digits to add more votes than the real ones for the Popular Front candidates in Jaén, where there were ballot boxes with more votes than voters; seriously adulterated recount in La Coruña; fraud in Cáceres, Valencia -with scrutinies behind closed doors without witnesses- or Santa Cruz de Tenerife, where “the unofficial victory of the centre-right turned into a short-lived triumph of the PF, which scored the four seats of the majorities”; diversion of votes in Berlanga, Don Benito and Llerena to the detriment of the CEDA (Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right wing parties). .. At least 10% of the total number of seats distributed (which amounts to more than 50) was not the result of free electoral competition, argue Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García, the authors of 1936: Fraude y Violencia. The book marks, according to historian Stanley G. Payne, “the end of the last of the great political myths of the 20th century”. “Spain has become Coruña”, wrote Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, referring to the generalisation of what happened in La Coruña, which for the former President of the Republic exemplified “those posthumous and shameful rectifications” that took place with the electoral records. If from the 240 seats won by the Frente Popular we subtract those that were the result of fraud, the remaining would not have been enough to form a government.

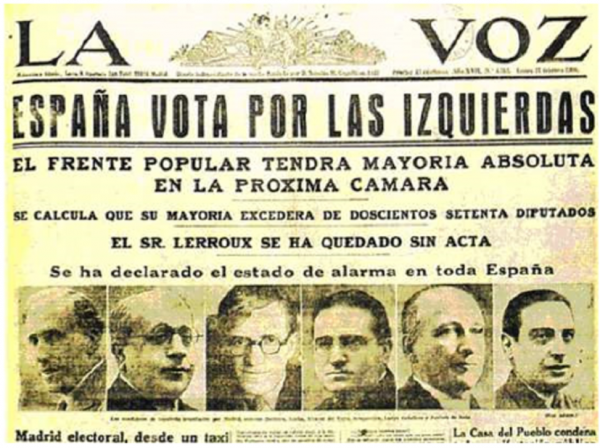

After meticulous detective work, consulting and dusting off the archives and minutes, one by one, of each province, as well as other primary sources – memories and press – the prestigious historians Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García have reconstructed, almost minute by minute, the account of the count of the last general elections before the Civil War. And they publish, for the first time, after consulting all the minutes, the official results of the elections of 16 February 1936, which went down in history as the great victory of the Popular Front and placed Manuel Azaña at the head of the Government of the Second Republic. They not only confirm that the right wing won by 700,000 votes in Spain as a whole, but also explain the most scandalous cases of fraud.

Incredible overturns and interrupted recounts of ballots. Ballots that appear at the last minute, en bloc and sometimes in open envelopes, to decide the result at a polling station. Others with erasures, erasures and scratches? In La Coruña, Orense, Cáceres, Málaga, Jaén, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Granada and Cuenca very strange things happened. All of them were influenced by a well-known but relatively unnoticed circumstance: in the middle of the recount – which took several days – the Portela government – whom the authors hold largely responsible for the mess – resigned. The new government, “Azaña’s men only”, as the President of the Republic, Alcalá Zamora, would say to emphasise that it was made up of secondary figures from the Republican Left and the Republican Union, conditioned the decisive hours of the count.

The February 1936 elections were clean; the campaign was very dirty. According to the authors, the campaign ended with 41 dead and 80 seriously wounded. Violence took hold on the streets and the elections took on a plebiscitary character in a foul, radicalised, polarised and cannibalistic atmosphere. They were elections on a war footing in which the future of the Republic seemed to be up in the air.

Now the book by historians and experts on the period, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García uncovers the truth of what happened. It is a massive and absolutely groundbreaking investigation which, as the Hispanist Stanley Payne stresses, puts an end to one of the “great political myths of the 20th century”.

Because the professors at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Álvarez teaches History of Political Thought there and Villa, Political History) dismantle the legends built up around the victory of the left. What happened during the days following the vote were not demonstrations of enthusiasm, celebration and jubilation by supporters of the Popular Front, but coercive and intimidating practices organised and instigated by the provincial interim authorities, who took advantage of the sudden change of government on the 19th. They spread throughout the country, generated a climate of legal uncertainty surrounding the count and influenced the results that were finally admitted.

In addition to publishing the official results of those elections for the first time, the authors identify cases of fraud, falsification and manipulation. They detail case by case, unexplained overturns and interrupted recounts; ballots that appear at the last minute, en bloc, in order to decide the result at one polling station and others with erasures, erasures and scratches. They show that slightly more than 10% of the total number of seats in these new Cortes, more than 50, was not the result of free electoral competition.

There was never a single official result sheet. The Provincial Boards reported the tally to the Central Board, which passed it on to Congress. The final tally was to appear in the statistical yearbooks of the following year. This was not the case. So far, historians made projections based on the relationship between the figures published in the press and the final allocation of seats.

The fraud was either directly promoted or passively supported by the Popular Front‘s interim provincial authorities, who acted with total impunity and were able to get hold of the electoral documentation after the change of government, which led to the resignation of the civil governors and presidents of the provincial councils or simply their expulsion or arrest – in some cases to preserve “their security”. Of course, the wave of violence unleashed between the 16th and 19th precipitated events. In some places, rioters forced the authorities of a leper hospital to let the sick go.

The elections were falsified, mainly at polling stations in Malaga and Santa Cruz de Tenerife, where the voting had to be repeated. Although without the supervision and presence of proxies of centrists and right-wing representatives. They were, according to the new book, a real farce.

On the 20th, 57 polling stations were to be reopened in the city of Malaga. No less than 29,000 votes were in dispute. The results of the 16th favoured the FP by a wide margin. It is therefore a mystery that the coalition changed its candidate (legal practice), the socialist Luis Dorado, who had to win 13,000 votes more than the right winger to secure his seat. The day before, PF militants occupied the headquarters of the Civil Government and replaced the governor with a sympathetic councillor. They did the same in the Town Hall and the Provincial Council. The new governor closed down the headquarters of the CEDA and Falange and arrested several members. Finally, the Cedista Emilio Hermida withdrew his candidacy (which did not prevent him from being voted in). There were riots and shootings, but everyone voted: some 29,000 registered voters. Almost 28,000 voted for the socialist Dorado.

In Santa Cruz de Tenerife the victory seemed assured for the centre-right representative, who had, according to the Civil Government and with the last polling stations still to be opened, a lead of 11,000 votes. The centrist Félix Benítez de Lugo, who considered himself the winner, called for a vote for the republican candidates to stop the socialists and communists (the electoral system was a list system with a majority in multi-member constituencies).

On the 19th there was an unexpected twist: PF candidates invited the governor to leave his post. The reason was simple: it made no sense for him to remain in office if his government had resigned. Members of UGT and CNT (unions) and the Popular Front demanded that Azaña open prisons to free the “social prisoners” in several cities and hand over the town halls to the left, the latter to prevent the right from altering the results. On the 20th a state of war was declared in the city. The radical candidate withdrew. A general strike was proclaimed and the elections were not held. However, in eight out of nine polling stations, Popular Front ballots appeared: 3,700 ghost votes which, together with other manipulations of the electoral rolls, contributed to the overturning of the result in the province.

Voters in the town of Alcaudete in Jaén were also due to vote on the 20th. They went to the polls while the Provincial Council was counting the votes. In all, the left won in this traditionally conservative fiefdom by 599 to 0. In Linares there were unsealed ballot boxes and in five of the province there were more votes than registered voters. Likewise, in Valencia, La Coruña and Cáceres ballot boxes were broken or intercepted.

In Valencia the forces were evenly matched. The change of government precipitated a messy recount in 21 municipalities: the left won by 400 votes, just enough. The Provincial Junta refused an official recount, because “it had already been done behind closed doors“.

Cover of the book 1936: Fraude y Violencia

In La Coruña the recount was prolonged until the 24th: the results of 188 tally sheets did not correspond with the certifications of the polling stations. “Spain has become Coruña”, wrote Alcalá Zamora. There the interim authorities demanded the immediate submission of the results of 56 polling stations and threatened a general strike if a solution “satisfactory to the left” was not found. Right-wing candidates were arrested for a day on charges of fraud.

And in seven municipalities of Cáceres the documentation arrived at the Provincial Board with the sealing torn and the envelopes opened. In five polling stations, the minutes of the voting disappeared. The investigators illustrate with many examples of similar manoeuvres that the change of authorities modified the final distribution of seats. They interrupted the count where the race was closest.

On the 20th, when the Provincial Boards met, the procedure to introduce confusion was similar in many places: the left denounced the right for manipulation and fraud, contested the results and even arrested their representatives. Up to that point, the Popular Front majority was only “taken for granted”.

Portela himself, whose seat for Pontevedra was up in the air, refused to advance results before the 20th. Some embassies were predicting a dead heat on the 18th, which made the second round decisive, but in the end it was irrelevant, despite the fact that it had to be held in a good number of provinces. The left put its propaganda apparatus into action: the Popular Front “would not let victory be snatched away”; “Do the half a million votes won in Madrid and Barcelona have the same value, politically, as the 50,000 wrested from the peasants of Palencia by the caciquismo?” The PCE’s (COmmunist Party) slogans were addressed to the new government, whose duty it was to adjust the Cortes, “freed of impurities”, to the electoral preferences, which had nothing to do with those of “a captain of industry like March”.

Women voting

The left was not prepared to accept a ballot that did not give them victory. According to the state of opinion that was created, on the basis of the advantage they had gained, any reversal during the ballot was fraudulent. The Popular Front would win in number of seats, but a sufficient parliamentary majority was at stake: 240 seats.

¡Bingo!, they won more than 50 seats in a dubious way. The numbers added up after the change of government, because before that date and in the first two days of counting, the figures handled by Alcalá Zamora, Azaña and the British ambassador coincided: between 216 and 217 deputies for the Popular Front. If from the 240 seats won by the Frente Popular we subtract those that were the result of fraud, the left alone would not have form a government. In total there were 473 seats up for grabs.

Azaña’s government was legal and legitimate, as it was up to the president to dissolve it and appoint another one, but his “political intelligence” does not come off well. This book details everything that happened in those four days. The 19th changed everything. After Portela’s “flight”, the Popular Front seized local power, which was decisive in conditioning the recount and creating an intimidating atmosphere. The unrest was not a reaction to rumours of a coup but to ensure a parliamentary majority for the Popular Front. The rule of law was de facto suspended.

The work that Tardío and Villa have done is prodigious. To prove the fraud they have followed a scrupulous method of verifying the legal and formal aspects of the elections. They then compared the votes counted at the polling stations with the results proclaimed by the polling stations – this is the mother of the fraud. And finally, they analysed the justification for the challenges.

It has been more than five years of investigation. They do not resort to secret documents. They are all public. They had to be purged, put in order and the puzzle had to be constructed. Most of the papers had not been consulted before. The authors have travelled around Spain and have scrutinised the archives of the British Foreign Office, the Quai d’Orsay and the Vatican archives to recount from different angles six decisive months in the history of Spain, from December 1935 to the spring of 1936.

The authors test the democratic quality of the Republic and argue that the CEDA resisted electorally. They show that there was a solid sociological basis for building an inclusive Republic. Unfortunately, they argue in conversation with Crónica, “the strategy of the Popular Front in the discussion of the acts in Congress and the fact that the Republican left, with Azaña at its head, did not stand up to socialist radicalism, was what once again dynamited the bridges of dialogue with the conservative opposition. This was a serious blow to the consolidation of the young republican democracy”. In any case, they do not encourage the revisionist theses that project certain events onto the coup of 1936. Rarely can it be said of a book that it is definitive. 1936: Fraude y Violencia is so.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021