Source:ABC

Believe it or not, Conchinchina existed. It is not a Spanish saying to cite what is far away. Conchinchina is what we know today as Vietnam and a Spanish contingent went there to defend the Dominican mission that was brutally attacked by the Spanish.

The temples of Angkor, in Cambodia, were the great unknown of the West until Henri Mouhot, a 19th century French explorer, discovered them. However, few knew then that 300 years earlier a pair of adventurous Spanish missionaries, Gabriel Quiroga de San Antonio and Diego Aduarte, had already witnessed for the first time the beauty and majesty of these architectural treasures. Two visionaries, no doubt, for Angkor has been a World Heritage Site since 1992.

The Spanish mission

Both friars corresponded routinely with King Felipe III. In their letters they already recounted the ins and outs of the Spanish spearhead in the Cochin-China region. Adventurers of Spanish lands in difficult terrain, they set out to conquer new experiences and riches for the Crown of Spain.

It is true that during the reign of Isabella II, Spain had little presence in Asia, with the exception of the Philippines, a very active colony where Spanish traders had their sights set and missionary activity was booming. This active life in favour of the Christianisation of the locals and the expansion of the culture of the bull skin, meant that little by little they moved towards the Cochin-China, today’s Vietnam.

The isolation of the missionaries and the adventurousness of their work led to a series of revolts that gradually became the breeding ground for the detonation of the Spanish mission in the Cochin-China: the murder of Spanish and French missionary monks. Burnt churches, destroyed schools and sacked missions inflamed the natural patriotic ardour of our ancestors. Sentiment overflowed with the murder of the Spanish bishop José María Díaz Sanjurjo. His head was cut off.

This spilling of Spanish blood put the Spanish Foreign Minister in check, who fleetingly communicated with his French counterpart. The latter announced that Napoleon III had already given orders for the French squadron to head for the area and requested the participation of the Spanish fleet stationed in the Philippines, to which the government immediately agreed, intoxicated with Spanish passion and in defence of the faith. But France did not have such noble intentions, and seeing that it did not possess any territory in the area, the situation seemed perfect for them to legitimise their expansionist ambitions, which were greatly favoured by Spain’s greedy position in the Philippines.

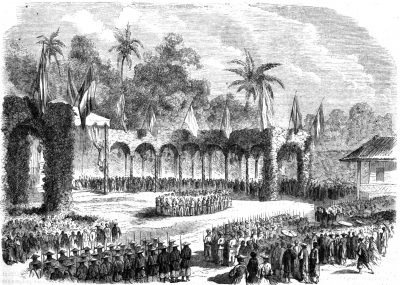

Spain sent a contingent of 1,650 soldiers from the Philippines who set sail under Colonel Bernardo Ruiz de Lanzarote, joining the French troops led by Rear Admiral Rigault de Genouilly. Later, in 1860, the Spanish mission was reinforced by an expedition corps under Colonel Carlos Palanca. The Spanish army added the warship Jorge Juan to the cause, which was later joined by the corvette Narváez and the schooner Constancia in 1860. An infantry regiment, two companies of Hunters, three sections of artillery and the auxiliary force reinforced the contingent and completed the determined and noble Spanish cause.

Although Colonel Palanca encountered a dramatic picture of the Franco-Spanish military campaign, in the end the joint punitive action won out. Our troops were strong and modern, and although the enemy was numerous, they could not defeat the European armies. But as time went on, the Spaniards realised the true intentions of the French and the Colonel informed the Spanish government. In the end, it was the French leader of the joint expedition who ordered the withdrawal of troops without the consent of the Spanish government. After the occupation of the southern part of the country, peace was signed on 14 April 1862 without any Spanish presence, and Emperor Tu ceded the occupied zone to France, leaving the Spanish army hanging and retreating.

France began its colonial penetration of Indochina and Spain was seen by the international community as a French sidekick. However, in the words of General José Cervera Pery, Auditor of the Navy’s Legal Corps and contributor to the Institute of Military History and Culture: “Spain returned with the pride of having done its duty and satisfied with the lesson well learned. Spain, traditionally allied with France, always suffered from illogical situations, for while the Spaniards moved in a crusading spirit, the French were always driven by other, more banal interests. But thanks to unsung heroes like General Palanca, the bravery and gallantry of the Spanish will always be on everyone’s lips.”

And so the Spaniards defended tooth and nail the adventurous missions that travelled there. Motivated by the spirit of crusade, they may not have accumulated vast tracts of Asian land, but the freedom of worship and the work of the Spanish missionaries remained intact. We Spaniards were the last in the Philippines and… the first in La Cochin-China.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021