Source:ABC

Contrasting what this party maintains in Granada, where the end of the conflict was agreed, with what they say in the Balearic Islands, where these days they commemorate the Diada de Mallorca, the conquest of what is now Palma by the troops of King Jaime I, who put 25,000 Muslims to the sword.

The Granada Abierta platform brings together trade unions, feminist associations and political parties such as Podemos and Izquierda Unida (Left United) in the persistent demand, year after year, to suspend all events celebrating the anniversary of the Fall of Granada, which was commemorated last Sunday (January 2nd) under capacity limitations due to the pandemic. This platform considers the festivity to be “racist and exclusionary”, a “historical falsification” of an event which, in their words, celebrates the non-fulfilment of the conditions signed by the Catholic Monarchs with the people of Granada and “hatred of diversity”.

What Podemos maintains in Granada, where the end of the conflict was agreed and even guaranteed safe conduct to all Muslims who wanted to leave the city, contrasts with what this same party believes in the Balearic Islands, where it is celebrating with its support these days the Diada de Mallorca, that is, the conquest of the ancient Madina Mayurga (now Palma) by the troops of King Jaime I, who put 25,000 Muslims to the sword as the icing on the cake of the campaign. But, above all, it is a present-day reading of a historical event that marked Spain’s passage towards modernity as a state and which took place at a time when politics and religion were one and the same thing.

At the dawn of the Modern Age, Granada became the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula. Postponed during the unstable reigns of Juan II and Enrique IV, the conquest of Granada became a priority for the Catholic Monarchs, who had grown up under the threat posed by the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which in 1453 succeeded in the taking of Constantinople, and were unwilling to tolerate the defiance of Muley Hacen, the emir of Granada, who during this period seized several strongholds on the Christian frontier and failed to pay the tribute stipulated with the Christians. Even the Arab chroniclers emphasised the bellicosity of this emir: “Magnanimous and courageous, a lover of wars and the dangers and horrors they caused”.

On learning in Medina del Campo of the Muslim attack on Zahara, Fernando, the Catholic King, said aloud: “I am sorry for the deaths of the Christians, but I am happy to put into action very quickly what we had in mind to do”. This place, whose inhabitants were enslaved or killed, had been conquered by the Aragonese’s grandfather, Fernando of Antequera, in 1410. It was a family matter for him to strike back.

Pope Sixtus VI supported the military enterprise by instituting a Crusade, by way of financial assistance. The Crusade bull was extended every two years until in its last year, 1492, it raised 500 million maravedis. Three quarters of the funds that financed this war, rich in episodes of great violence on both sides, came from ecclesiastical taxes. The nobility, the high clergy, Italian bankers and the Jewish communities provided the rest of the funds. In addition, important economic remittances arrived from various European countries and, above all, German, English, Burgundian and German knights and adventurers came to take part in the last Crusade of the Christian West.

Nor was the popular support for the Granada enterprise in Spain any less significant. “Wherever they went, men, children and women met them from all over the countryside and showered them with a thousand blessings: they called them the protection of Spain (…)”, wrote Father Mariana of the popular fervour unleashed by the passage of the troops. Having just pacified Castile from its successive internal wars, the Catholic Monarchs used the figure of the common enemy to engage the kingdom’s unruly magnates in a campaign where old rivals fought side by side.

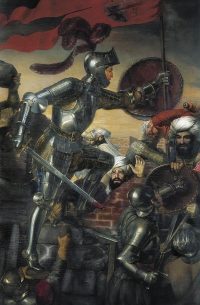

The Christians had numerical superiority and morale on their side, but the characteristics of the terrain stretched out a war of sieges and skirmishes, without major battles in the open field, over six years. In this time, the Catholic Monarchs developed a military apparatus, an administration and a system of taxation, the ultimate goal of which was a modern state that the kings of the House of Habsburg subsequently used to achieve hegemony in Europe.

The ‘Small King’ sowed discord in Granada

During the first stage of the war, between 1482 and 1484, improvisation and the isolated actions of great Andalusian nobles, including the Duke of Medina-Sidonia and the Count of Cabra, elder brother of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, set a slow pace in the conflict. Christian luck improved in the second stage, as the armies of Isabel and Fernando increased their performance and conquered the valleys of Ronda, Loja, Marbella, Baza, and Malaga, an essential port for the Muslims to receive supplies and reinforcements from North Africa.

Of particular importance was the fact that the Catholic Monarchs associated themselves with Prince Abu Abd Allah, known to the Spanish as Boabdil “The Small King”, which plunged the Muslim side into civil war. The son of King Muley Hacen and Aixa, the sovereign’s cousin, Boabdil grew up under a long prophecy that stated, from birth, that he would bring death to all who loved him, and between his hands the crescent moon would be transformed into a cross. But it was not words, but scandals, that drove the heir away from his father, Muley Hacén, who relegated Aixa to the background in favour of a Christian concubine from the harem. Aixa, who tried unsuccessfully to kill the Christian woman and her children, incited Boabdil to rebel against her father by using her many allies among the Nasrid aristocracy, for it should not be forgotten that she was the daughter of a previous sultan.

The stern Muley Hacen believed that Boabdil, a courteous man, “affable and with elegant manners”, was not fit to reign in Granada, not least because his temperament bore little or no resemblance to his own. It was wrong of him to underestimate his son… Taking advantage of the fact that Hacen was away fighting with the Christians, Boabdil and his mother raised what the Arab chroniclers called “a terrible rebellion that broke the hearts of the people of Granada”. In 1482, the emir suffered a coup d’état by his son and by an important faction in the city, allied with Aixa. Hacen was forced to return to his capital at full speed.

In the midst of this civil war, Boabdil set out to prove that he too was a skilled warrior. Seeking a prestigious victory, Boabdil assaulted the city of Lucena, in the Castilian hinterland, which became a fierce melee battlefield. Some of Granada’s best officers died that day, while the Small King was captured while trying to save his horse from drowning. Fernando and Isabel treated him with respect and agreed to release him in exchange for a large ransom, vassalage and the promise of an annual tribute payment. With no other option, he agreed.

On his return to Granada, Boabdil was received as a hero by many, as many as suspected that he had made a pact with the enemy. The struggle of both sides intensified with his return, especially on the death of Muley Hacen in 1485, who left the city dying with his Christian wife after ceding the throne to his brother Ibn Sad, known as “the Kid”, an experienced commander.

This rivalry between Boabdil and his uncle coincided with great Christian advances, so that the two emirs divided the city in two and, at least in appearance, reconciled to confront the Catholic Monarchs. The latter, unsurprisingly, saw Boabdil’s move as a breach of his oath of loyalty and fidelity to them. Hence, when the prince fell back into their hands after the fall of Loja, they forced him to further specify the terms of his vassalage: he would help the Christians, once he was freed again, in exchange for their help in overthrowing his uncle. Boabdil maintained secret contacts with the Catholic Monarchs from then on, many of them through his friend and confidant Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, who would be nicknamed by the Italians as the Great Captain, and who became very important in the final phase of the conflict thanks to his knowledge of the Arabic language.

With the help of Isabel and Fernando, Ibn Sad was expelled from Granada and the prince made king. Boabdil became a loyal ally of the Christians, to whom he promised to hand over Granada as soon as he could as part of an exchange of places in the eastern part of the kingdom that were then loyal to “the Kid”. Whether Boabdil could find a way to get out alive if he surrendered the city without fighting was another matter. Little was left by then of the much-vaunted tolerance between Muslims, Christians and Jews, nor of the cultural splendour that had given rise to one of the most beautiful cities in the West. Gradually, the city of Granada was filled with radicalised refugees, who were looking for a last place to resist until death.

Faced with the secret agreement between the Catholic Monarchs and the last king of Granada, “the Kid” responded in kind. In December 1489, Boabdil’s uncle was convinced that all resistance was in vain, surrendered the port of Almería and abandoned Guadix before the year was out. He sold his possessions in Andalusia and left for his new home in North Africa, leaving his nephew landlocked. There was no shortage of Arab chroniclers, such as Nubdhat Al-ASr, who saw his manoeuvre as a convoluted way of taking revenge on Boabdil:

Many people claim that “the Kid” and his commanders sold these villages and districts they ruled to the ruler of Castile and received a price in return. All this with a view to taking revenge on his brother’s son […] and his commanders who were in Granada, alone with the city already under his rule and benefiting from a truce given by the enemy. With this act he wanted to isolate Granada, to destroy it in the same way as the rest of the country had been destroyed.

The emir did not weep; he withdrew to his new possessions.

The actions of the winter of 1490 proved the precariousness of Granada’s defences. As recounted by José María Sánchez de Toca and Fernando Martínez Laínez in El Gran Capitán (EDAD, 2015), Hernán Pérez del Pulgar, famous for his feats, entered Granada at night with 15 of his men, nailed the Hail Mary to the door of the Great Mosque with his dagger and, on leaving, set fire to the city’s market. Around those days, the attempt to free the 7,000 Christian captives imprisoned in Granada’s prisons failed. Most of them died of starvation during the siege.

To intensify the pressure on the emir, in the summer of 1491 the Catholic Monarchs began the construction of the Santa Fe camp, built in a grid pattern in front of Granada, with the firm decision that it would only be lifted after the fall of the city. They did not bring artillery with them, as they had no intention of destroying the city. On 25 November 1491, the monarchs signed the final agreement with Boabdil to surrender the city. The monarchs agred to respect the property and people living in Granada, to guarantee freedom of worship, and that Koranic law would continue to be used to settle disputes between Muslims. The agreement also included a promise that there would be no punishment for the tornadizos (turncoats), elches (captive christians turned Muslims) and marranos (Jews) who had taken refuge in Granada, and that they would be facilitated to move to North Africa.

In return for this benign agreement, “The Small King” agreed to surrender Granada within two months, a condition that was difficult to fulfil because of the threat of widespread mutiny against the last king of Granada. With the emir’s permission, a Christian advance guard occupied the Alhambra, pre-empting any violent reaction from the people, which was followed by the surrender of the city. A Basque chronicler described that day as the one that “redeemed Spain, even the whole of Europe” from its sins.

In Rome, the end of the Crusade was celebrated with bell-ringing, bull running, and bullfights. The conquerors were called “athletes of Christ”, and the monarchs were given the title of “Catholics”, by which they are now known in history books. It is no coincidence, therefore, that Isabel and Fernando chose Granada to lay their remains to rest in the Capilla de los Reyes (Chapel of the Kings) in the Cathedral.

On 2 January 1492 the surrender was staged in a ceremony devoid of humiliation, as evidenced by the fact that Boabdil did not kiss the hands of the Monarchs. He handed the keys of the city to the Count of Tendilla, Íñigo López de Mendoza, who was to be the first Captain General of the Alhambra. According to the Chronicle of the Catholic Monarchs, Boabdil advanced on his horse facing the enemy encamped beyond the walls of Granada and then a crowd of starving people, composed of wailing mothers and children “shouting that they could not suffer hunger; and that for this reason they would come to abandon the city and go to the kingdom of their enemies, for which reason the city would be taken and all would be taken captive and killed”.

Surrender had been the only possible way out. The last emir continued to live in the Peninsula, in a territory assigned by the Kings in the Alpujarras, but after eighteen months he crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to die in Fez decades later. The conditions signed by the Monarchs were initially respected and all those who wished to leave the Peninsula were allowed to do so. The Mudejar population came to be treated more firmly after the visit of the Queen’s new confessor, Cardinal Cisneros (1499). As a result, there was an increase in “conversions”, but also a series of violent disorders that lasted until late in the 16th century.

These episodes, not surprisingly, were seen as a breach of the conditions of the capitulation by the Islamic side, and so, unrestrained, the Monarchs issued the Pragmatic Decree of 11 February 1502, which obliged the Muslims to be baptised or exiled. As the century progressed and the threat of the Turks using Granada as a bridgehead for a direct attack on Spain grew, the policy of evangelisation, preaching and catechisation gave way to extreme measures. In 1526, Carlos V suspended, in exchange for the payment of 80,000 ducats, the prohibition of all the distinctive elements of the Moors, such as language, dress, bathing, worship ceremonies, the rites that accompanied them, the zambras. This extension would come to an end in the reign of Felipe II.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021