Source:Afán

Venezuela had ended the year 1813 in the midst of plunder, ruin, and desolation. Trade and commerce had languished to extinction. Money was scarce, as exports had also suffered. What circulated was low grade money and even bone tokens called “señas”. The state forced people to hand over their silver objects at a discount of 25% of their value for the minting of coins, which were again being forced out of circulation by the need to import basic goods and war supplies. The shortage of money forced the state to turn to the clergy, who were obliged to hand over their jewelry not essential to worship in order to convert it into coins. The countryside suffered similar desolation. Farmers stopped farming because of the general fall in prices, while at the same time they fell victim to marauders who preyed on them.

Insecurity was total. Farms and estates were abandoned, so the state confiscated many of them and sold them at ridiculous prices. People found that their property was worthless and the money they got for it was eaten up by inflation. The country had been wrecked and the productive classes had fled with what little they had left. Hunger and food shortages were rife. Social life was paralysed; civil and criminal justice was non-existent, sentences scarce and biased; judges, mostly military, corrupt or on leave. Counter-revolution had intensified in 1814 and bands of outlaws swarmed everywhere, robbing houses, marauding roads, extorting people, and ravaging everything. The success of the secession was in jeopardy. The royalists were growing ever stronger because of the excesses and abuses of the independence fighters. Bolívar wrote:

“Terrible days we are living through: blood is flowing in torrents: three centuries of culture, enlightenment, and industry have disappeared: ruins of nature or of war appear everywhere. It seems that all evils have been unleashed on our unfortunate peoples.”

In mid-June, the second battle of La Puerta, where the liberator was to be defeated by Boves, was destined to be a milestone in the political thinking of the man who was later to nurture the worst betrayal of all: handing America over to Spain’s secular enemy, Great Britain, as well as having brought about, the following month, the greatest humanitarian disaster ever recorded: the exodus from Caracas, which claimed the lives of thousands of citizens, men, women and children, forced by Bolívar to flee the city and march for 23 days towards the East, while the liberator fled with about 1150 kilograms of carved silver and jewellery that he had put in 24 crates and shipped to La Guaira on 7 July for Cumaná, the product of the looting of the churches!

There were monstrances, ciboria, chalices, candelabra, jewels, precious stones and various other sacred ornaments which, it was agreed, were to be divided between Bolívar and Mariño, his emulator in the East, where he was going.

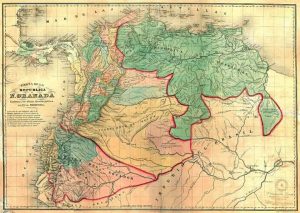

New Granada, it is true, was in a less distressing situation, but it was also in a state of ruin everywhere. News that Spain was already liberated and was preparing to send troops to the revolted provinces was another source of concern for the insurgents. Indeed, Spain was beginning to rise from the ashes of the war against Napoleon, who would soon have to defend himself on his own soil, the south of France, invaded by English and Spanish troops led by General Pablo Morillo. So the Republican misfortunes on the battlefield came as no surprise to anyone in 1815 when Venezuela and New Granada in 1816 were pacified by Pablo Morillo’s troops and the ringleaders of the New Granada rebellion were put in captivity and executed. Law and order were re-established in both territories.

However, a new air of foreign affectation was already in the air in America, particularly in New Granada and Venezuela. Bolívar was forgetting his Negroid features and origins and was basking in the idea of becoming a vassal of the most slave-owning country in the world, England, which had taken racial discrimination to unsuspected limits in its American colonies, discrimination that would continue for the next two centuries of independence. Indeed, while England, after the Treaty of Utrecht, was increasing its fleet carrying slaves throughout the lands of the New World; while the factories of London and Manchester were spitting smoke and soot in the faces of their inhabitants; while the children were breathing the poisoned air of the factories and the Thames was carrying the filthy waters of pestilence and hell was being created on earth, the Creoles, who had already awakened from Frenchness, were now opening their eyes to Anglophilia to begin to change their side and settle down on the soft mattress of the victor of Waterloo.

Bolivar, the so-called liberator of five republics, since his escape to Jamaica in 1815, saw more clearly that submission to Britain was the answer to Spain, devastated by the war against the tyrant of Europe. Bolívar was a romantic and, like all romantics, a dreamer. He believed that to surrender America to the British was to achieve “eternal bliss”, as he wrote in 1826. As early as 1811, shortly after going to London, he entertained the idea that England would be very happy to get even for Spanish interference in the war of independence in its northern colonies. Would it not be possible to propose to the British to make up for their colonial losses by handing over Spanish America to them as a protectorate, a factory, a colony, a possession, or whatever? Were they not already on the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua and even in the Darien, and why not start by giving them Panama, and was that whole region, from Cartagena to Portobelo, not only uninhabited but highly vulnerable? All these ideas needed to be aired in London, and no one better to undertake such a task than Andrés Bello, the theoretical representative of a triumphant revolutionary government. Yes, Bolivar and Miranda had to return to consolidate the triumph that made England look like the saviour of Spain, now that its power was increasing at the expense of the war that was growing in ferocity on the Peninsula.

It was the same war that Bolivar had ambitions to wage against Spain on American soil. It had to be split to pieces, taken on two fronts, simultaneously; its legacy had to be swept away, and even the English language had to be adopted, no matter that he himself stammered in it and barely made himself understood by the masters he sought. These were minor, unimportant details. But what of what he later wrote that “experience has shown us that even when excited by the most seductive stimuli, the Spanish servant has not fought against his master”? Yes, but Bolivar was counting on the pure-blooded Creoles, the oligarchs, the Frenchified, who could easily change their flag and adopt the English one, because that was the one that was now emerging victorious, and there is nothing more flattering than to be with the victor. Or was it not already in 1816 that English-style social clubs were forming in Santa Fe, and was not Freemasonry, formerly French, now largely crypto-Scottish? Was it not becoming clear that it was better to surrender to British power than to Spanish power, which was going to pay dearly for the betrayal, a charge that was already underway in 1816?

This is why Bolívar in Jamaica called on England to impose a New Order in America after the defeat of the Bourbons, who by this time had returned to Spain. “The great American federation cannot be achieved if the English do not protect it with their soul and body”, he was to say. That is why he also wrote to Maxwell Hyslop, the British merchant who lent him economic aid in exchange for ethereal promises and such shenanigans as “the mountains of New Granada are of gold and silver…”, He wrote, I say, the following: “It is time, sir, and perhaps it is the last period in which England can and should take any part in the fate of this immense hemisphere which is to succumb or be exterminated if a powerful nation does not lend her support…but the incalculable loss to be made by Great Britain consists of the whole southern continent of the Americas, which, protected by her arms and commerce, would extract from her bosom, in the short space of only ten years, more precious metals than circulate in the universe… I wish to continue to serve my country for the good of mankind and the increase of British commerce….”

Judge, then, the reader, whether Bolivar’s real dream was to achieve the freedom he wanted to give to Spanish America. Bolivar embodied the most utopian idealism, the most puerile grandiloquence, the most servile abjection.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021